Early Theories of Media Effects

A major goal of scientific research is to develop theories or laws that can consistently explain or predict human behavior. The varied impacts of the mass media and the diverse ways in which people make popular culture, however, tend to defy predictable rules. Historical, economic, and political factors influence media industries, making it difficult to develop systematic theories that explain communication. Researchers developed a number of small theories, or models, that help explain individual behavior rather than the impact of the media on large populations. But before these small theories began to emerge in the 1970s, mass media research followed several other models. Developing between the 1930s and the 1970s, these major approaches included the hypodermic-needle, minimal-effects, and uses and gratifications models.

The Hypodermic-Needle Model

VideoCentral  Mass Communication

Mass Communication

Media Effects Research

Experts discuss how media effects research informs media development.

Discussion: Why do you think the question of media’s effects on children has been such a continually big concern among researchers?

One of the earliest media theories attributed powerful effects to the mass media. A number of intellectuals and academics were fearful of the influence and popularity of film and radio in the 1920s and 1930s. Some social psychologists and sociologists who arrived in the United States after fleeing Germany and Nazism in the 1930s had watched Hitler use radio, film, and print media as propaganda tools. They worried that the popular media in America also had a strong hold over vulnerable audiences. This concept of powerful media affecting weak audiences has been labeled the hypodermic-needle model, sometimes also called the magic bullet theory or the direct effects model. It suggests that the media shoot their potent effects directly into unsuspecting victims.

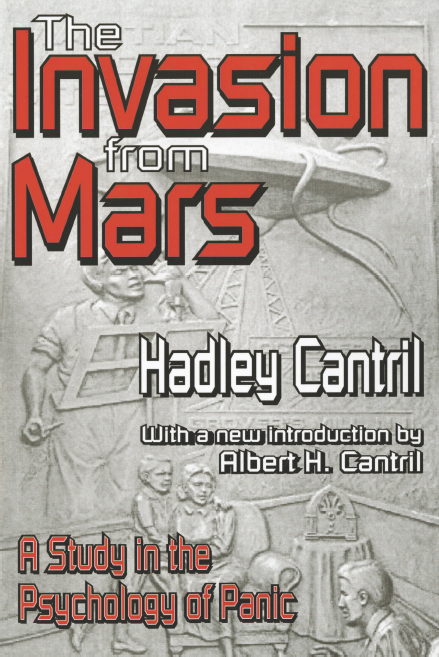

One of the earliest challenges to this theory involved a study of Orson Welles’s legendary October 30, 1938, radio broadcast of War of the Worlds, which presented H. G. Wells’s Martian invasion novel in the form of a news report and frightened millions of listeners who didn’t realize it was fictional (see Chapter 5). In a 1940 book-length study of the broadcast, The Invasion from Mars: A Study in the Psychology of Panic, radio researcher Hadley Cantril argued that contrary to expectations according to the hypodermic-needle model, not all listeners thought the radio program was a real news report. Instead, Cantril, after conducting personal interviews and a nationwide survey of listeners and analyzing newspaper reports and listener mail to CBS Radio and the FCC, noted that although some did believe it to be real (mostly those who missed the disclaimer at the beginning of the broadcast), the majority reacted out of collective panic, not out of a gullible belief in anything transmitted through the media. Although the hypodermic-needle model over the years has been disproved by social scientists, many people still attribute direct effects to the mass media, particularly in the case of children.

The Minimal-Effects Model

In The Invasion from Mars: A Study in the Psychology of Panic, Hadley Cantril (1906 ± 1969) argued against the hypodermic-needle model as an explanation for the panic that broke out after the War of the Worlds radio broadcast. A lifelong social researcher, Cantril also did a lot of work in public opinion research, even working with the government during World War II.

Cantril’s research helped to lay the groundwork for the minimal-effects model, or limited model. With the rise of empirical research techniques, social scientists began discovering and demonstrating that media alone cannot cause people to change their attitudes and behaviors. Based on tightly controlled experiments and surveys, researchers argued that people generally engage in selective exposure and selective retention with regard to the media. That is, people expose themselves to the media messages that are most familiar to them, and they retain the messages that confirm the values and attitudes they already hold. Minimal-effects researchers have argued that in most cases mass media reinforce existing behaviors and attitudes rather than change them. The findings from the first comprehensive study of children and television—by Wilbur Schramm, Jack Lyle, and Edwin Parker in the late 1950s—best capture the minimal-effects theory:

For some children, under some conditions, some television is harmful. For other children under the same conditions, or for the same children under other conditions, it may be beneficial. For most children, under most conditions, most television is probably neither particularly harmful nor particularly beneficial.12

In addition, Joseph Klapper’s important 1960 research study, The Effects of Mass Communication, found that the mass media only influenced individuals who did not already hold strong views on an issue and that the media had a greater impact on poor and uneducated audiences. Solidifying the minimal-effects argument, Klapper concluded that strong media effects occur largely at an individual level and do not appear to have large-scale, measurable, and direct effects on society as a whole.13

The minimal-effects theory furthered the study of the relationship between the media and human behavior, but it still assumed that audiences were passive and were acted upon by the media. Schramm, Lyle, and Parker suggested that there were problems with the position they had taken on effects:

“If we’re a nation possessed of a murderous imagination, we didn’t start the blood-letting. Look at Shakespeare, colossus of the Western canon. His plays are written in blood.”

SCOT LEHIGH, BOSTON GLOBE, 2000

In a sense the term “effect” is misleading because it suggests that television “does something” to children. The connotation is that television is the actor, the children are acted upon. Children are thus made to seem relatively inert; television, relatively active. Children are sitting victims; television bites them. Nothing can be further from the fact. It is the children who are most active in this relationship. It is they who use television, rather than television that uses them.14

Indeed, as the authors observed, numerous studies have concluded that viewers—especially young children—are often actively engaged in using media.

The Uses and Gratifications Model

In 1952, audience members at the Paramount Theater in Hollywood donned 3-D glasses for the opening night screening of Bwana Devil, the first full-length color 3-D film. The uses and gratifications model of research investigates the appeal of mass media, such as going out to the movies.

A response to the minimal-effects theory, the uses and gratifications model was proposed to contest the notion of a passive media audience. Under this model, researchers—usually using in-depth interviews to supplement survey questionnaires—studied the ways in which people used the media to satisfy various emotional or intellectual needs. Instead of asking, “What effects do the media have on us?” researchers asked, “Why do we use the media?” Asking the why question enabled media researchers to develop inventories cataloguing how people employed the media to fulfill their needs. For example, researchers noted that some individuals used the media to see authority figures elevated or toppled, to seek a sense of community and connectedness, to fulfill a need for drama and stories, and to confirm moral or spiritual values.15

Although the uses and gratifications model addressed the functions of the mass media for individuals, it did not address important questions related to the impact of the media on society. Once researchers had accumulated substantial inventories of the uses and functions of media, they often did not move in new directions. Consequently, uses and gratifications never became a dominant or enduring theory in media research.