Communication Policy and the Internet

“The FCC’s only goal here is to make sure that the Internet we know and love does not become corrupted and altered by a small number of large corporations controlling the last free and open distribution channel we have in this country.”

U.S. SEN. AL FRANKEN (D-MN), 2011

Many have looked to the Internet as the one true venue for unlimited free speech under the First Amendment because it is not regulated by the government, it is not subject to the Communications Act of 1934, and little has been done in regard to self-regulation. Its current global expansion is comparable to that of the early days of broadcasting, when economic and technological growth outstripped law and regulation. At that time, noncommercial experiments by amateurs and engineering students provided a testing ground that commercial interests later exploited for profit. In much the same way, amateurs, students, and various interest groups have explored and extended the communication possibilities of the Internet. They have experimented so successfully that commercial vendors have raced to buy up pieces of the Internet since the 1990s.

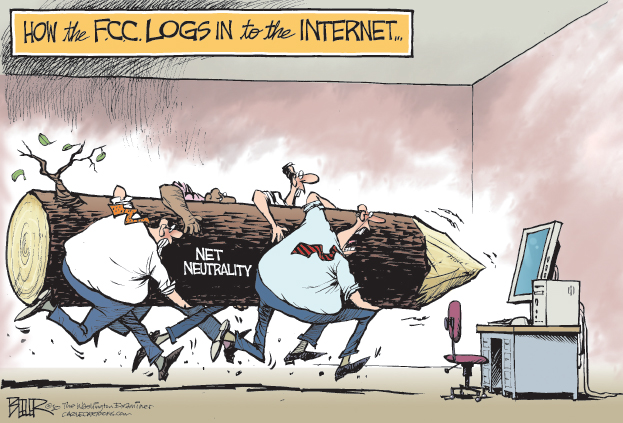

Public conversations about the Internet have not typically revolved around ownership. Instead, the debates have focused on First Amendment issues such as civility and pornography. Not unlike the public’s concern over television’s sexual and violent images, the scrutiny of the Internet is mainly about harmful images and information online, not about who controls it and for what purposes. However, as we watch the rapid expansion of the Internet, an important question confronts us: Will the Internet continue to develop as a democratic medium? By 2011, the answer to that question was still unclear. In late 2010, the FCC created net neutrality rules for wired (cable and DSL) broadband providers, requiring that they provide the same access to all Internet services and content. Yet, these new rules exempted wireless (mobile phone) broadband providers, enabling them to block Web services as they wish. Early in 2011, the U.S. House of Representatives moved to overturn the FCC net neutrality regulations. But in November 2011, the U.S. Senate voted to keep in place federal net neutrality rules and to preserve open Internet access. Nonetheless, the battle continues, and its eventual outcome will determine whether the broadband Internet connections will be defined as an essential utility to which everyone has access and for which rates are controlled (like water or electricity), or an information service for which Internet service providers can charge as much as they wish (as with cable TV).

Critics and observers hope that a vigorous debate about ownership will develop—a debate that will go beyond First Amendment issues. The promise of the Internet as a democratic forum encourages the formation of all sorts of regional, national, and global interest groups. In fact, many global movements use the Internet to fight political forms of censorship. Human Rights Watch, for example, encourages free-expression advocates to use blogs “for disseminating information about, and ending, human rights abuses around the world.”21 Where oppressive regimes have tried to monitor and control Internet communication, Human Rights Watch suggests bloggers post anonymously to safeguard their identity. Just as fax machines, satellites, and home videos helped expedite and document the fall of totalitarian regimes in Eastern Europe in the late 1980s, the Internet helps spread the word and activate social change today.