Unprotected Forms of Expression

Despite the First Amendment’s provision that “Congress shall make no law” restricting speech, the federal government has made a number of laws that do just that, especially concerning false or misleading advertising, expressions that intentionally threaten public safety, and certain speech restrictions during times of war or other national security concerns.

Beyond the federal government, state laws and local ordinances have on occasion curbed expression, and over the years the court system has determined that some kinds of expression do not merit protection under the Constitution, including seditious expression, copyright infringement, libel, obscenity, privacy rights, and expression that interferes with the Sixth Amendment.

Seditious Expression

“Consider what would happen if—during this 200th anniversary of the Bill of Rights—the First Amendment were placed on the ballot in every town, city, and state. The choices: affirm, reject, or amend.

I would bet there is no place in the United States where the First Amendment would survive intact.”

NAT HENTOFF, WRITER, 1991

For more than a century after the Sedition Act of 1798, Congress passed no laws prohibiting dissenting opinion. But by the twentieth century the sentiments of the Sedition Act reappeared in times of war. For instance, the Espionage Acts of 1917 and 1918, which were enforced during World Wars I and II, made it a federal crime to disrupt the nation’s war effort, authorizing severe punishment for seditious statements.

In the landmark Schenck v. United States (1919) appeal case during World War I, the Supreme Court upheld the conviction of a Socialist Party leader, Charles T. Schenck, for distributing leaflets urging American men to protest the draft, in violation of the recently passed Espionage Act. In upholding the conviction, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote two of the more famous interpretations and phrases in the First Amendment’s legal history:

But the character of every act depends upon the circumstances in which it is done. The most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theater and causing a panic.

The question in every case is whether the words used are used in such circumstances and are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent.

In supporting Schenck’s sentence—a ten-year prison term—Holmes noted that the Socialist leaflets were entitled to First Amendment protection, but only during times of peace. In establishing the “clear and present danger” criterion for expression, the Supreme Court demonstrated the limits of the First Amendment.

And in 2010, after WikiLeaks released thousands of confidential U.S. embassy cables into the public domain, the U.S. Justice Department contemplated charging the Web site’s founder Julian Assange with violating the 1917 Espionage Act. Assange took refuge inside the Ecuadorian embassy in London in June 2012, where he was granted diplomatic asylum. The U.S. government instead pursued Espionage Act charges against Private First Class Bradley (now Chelsea) Manning, an intelligence analyst in Iraq, who admitted to releasing the information to WikiLeaks to show the flaws of U.S. strategies in Iraq and Afghanistan. Manning was convicted and sentenced to thirty-five years in prison in August 2013.

Copyright Infringement

Appropriating a writer’s or an artist’s words or music without consent or payment is also a form of expression that is not protected as speech. A copyright legally protects the rights of authors and producers to their published or unpublished writing, music, lyrics, TV programs, movies, or graphic art designs. When Congress passed the first Copyright Act in 1790, it gave authors the right to control their published works for fourteen years, with the opportunity for a renewal for another fourteen years. After the end of the copyright period, the work enters the public domain, which gives the public free access to the work. The idea was that a period of copyright control would give authors financial incentive to create original works, and that the public domain gives others incentive to create derivative works.

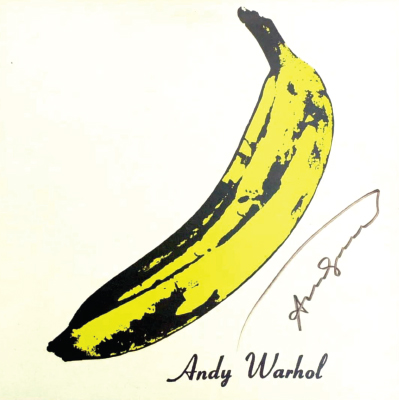

The iconic album art for the Velvet Underground’s 1967 debut, a banana print designed by artist Andy Warhol, has been a subject of controversy in recent years as a copyright dispute between the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts and the rock band has continued to flourish. The most recent disagreement occurred when the Warhol Foundation, which has previously accused the Velvet Underground of violating their claim to the print, announced plans to license the banana design for iPhone cases. Accusing the foundation of copyright violation, the band filed a copyright claim to the design, which a federal judge later dismissed.

Over the years, as artists lived longer, and more important, as corporate copyright owners became more common, copyright periods were extended by Congress. In 1976, Congress extended the copyright period to the life of the author plus fifty years, or seventy-five years for a corporate copyright owner. In 1998 (as copyrights on works such as Disney’s Mickey Mouse were set to expire), Congress again extended the copyright period for twenty additional years. As Stanford law professor Lawrence Lessig observed, this was the eleventh time in forty years that the terms for copyright had been extended.13 (See “Examining Ethics: A Generation of Copyright Criminals?”.)

Corporate owners have millions of dollars to gain by keeping their properties out of the public domain. Disney, a major lobbyist for the 1998 extension, would have lost its copyright to Mickey Mouse in 2004 but now continues to earn millions on its movies, T-shirts, and Mickey Mouse watches through 2024. Warner/Chappell Music, which owns the copyright to the popular “Happy Birthday to You” song, will keep generating money on the song at least through 2030, and even longer if corporations successfully pressure Congress for another extension.

Today, nearly every innovation in digital culture creates new questions about copyright law. For example, is a video mash-up that samples copyrighted sounds and images a copyright violation or a creative accomplishment protected under the concept of fair use (the same standard that enables students to legally quote attributed text from other works in their research papers)? Is it fair use for a blog to quote an entire newspaper article, as long as it has a link and an attribution? Should news aggregators like Google News and Yahoo! News pay something to financially strapped newspapers when they link to their articles? One of the laws that tips the debates toward stricter enforcement of copyright is the Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998, which outlaws any action or technology that circumvents copyright protection systems. In other words, it may be illegal to merely create or distribute technology that enables someone to make illegal copies of digital content, such as a music file or a DVD.

Libel

The biggest legal worry that haunts editors and publishers is the issue of libel, a form of expression that, unlike political expression, is not protected as free speech under the First Amendment. libel refers to defamation of character in written or broadcast form; libel is different from slander, which is spoken language that defames a person’s character. Inherited from British common law, libel is generally defined as a false statement that holds a person up to public ridicule, contempt, or hatred or injures a person’s business or occupation. Examples of libelous statements include falsely accusing someone of professional dishonesty or incompetence (such as medical malpractice); falsely accusing a person of a crime (such as drug dealing); falsely stating that someone is mentally ill or engages in unacceptable behavior (such as public drunkenness); or falsely accusing a person of associating with a disreputable organization or cause (such as the Mafia or a neo-Nazi military group).

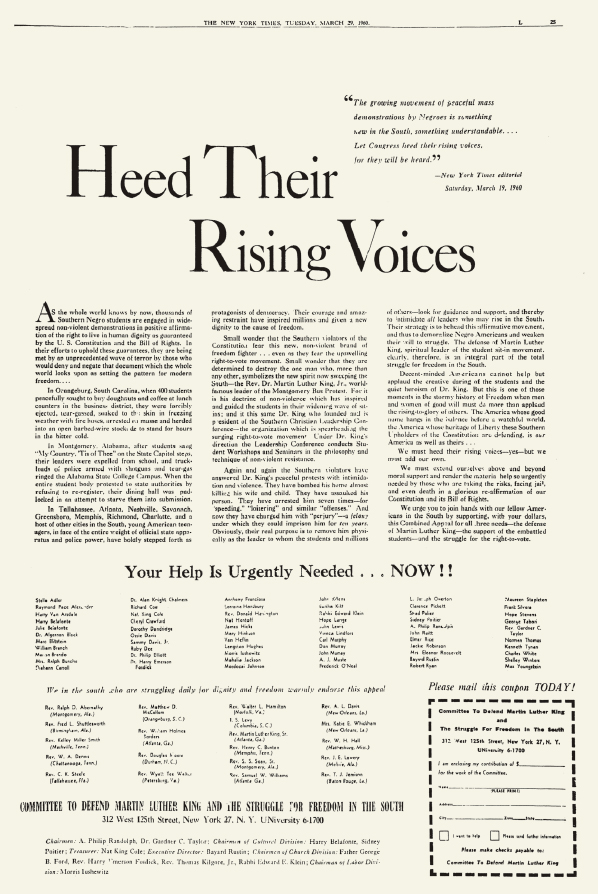

This is the 1960 New York Times advertisement that triggered one of the most influential and important libel cases in U.S. history.

Since 1964, the New York Times v. Sullivan case has served as the standard for libel law. The case stems from a 1960 full-page advertisement placed in the New York Times by the Committee to Defend Martin Luther King and the Struggle for Freedom in the South. Without naming names, the ad criticized the law-enforcement tactics used in southern cities—including Montgomery, Alabama—to break up Civil Rights demonstrations. The ad condemned “southern violators of the Constitution” bent on destroying King and the movement. Taking exception, the city commissioner of Montgomery, L. B. Sullivan, sued the Times for libel, claiming the ad defamed him indirectly. Although Alabama civil courts awarded Sullivan $500,000, the newspaper’s lawyers appealed to the Supreme Court, which unanimously reversed the ruling, holding that Alabama libel law violated the Times’ First Amendment rights.14

As part of the Sullivan decision, the Supreme Court asked future civil courts to distinguish whether plaintiffs in libel cases are public officials or private individuals. Citizens with more “ordinary” jobs, such as city sanitation employees, undercover police informants, nurses, or unknown actors, are normally classified as private individuals. Private individuals have to prove (1) that the public statement about them was false; (2) that damages or actual injury occurred (such as the loss of a job, harm to reputation, public humiliation, or mental anguish); and (3) that the publisher or broadcaster was negligent in failing to determine the truthfulness of the statement.

There are two categories of public figures: (1) public celebrities (movie or sports stars) or people who “occupy positions of such pervasive power and influence that they are deemed public figures for all purposes” (such as presidents, senators, mayors, etc.), and (2) individuals who have thrown themselves—usually voluntarily but sometimes involuntarily—into the middle of “a significant public controversy,” such as a lawyer defending a prominent client, an advocate for an antismoking ordinance, or a labor union activist.

Public officials also have to prove falsehood, damages, negligence, and actual malice on the part of the news medium; actual malice means that the reporter or editor knew the statement was false and printed or broadcast it anyway, or acted with a reckless disregard for the truth. Because actual malice against a public official is hard to prove, it is difficult for public figures to win libel suits. The Sullivan decision allowed news operations to aggressively pursue legitimate news stories without fear of continuous litigation. However, the mere threat of a libel suit still scares off many in the news media. Plaintiffs may also belong to one of many vague classification categories, such as public high school teachers, police officers, and court-appointed attorneys. Individuals from these professions end up as public or private citizens depending on a particular court’s ruling.

Defenses against Libel Charges

“You cannot hold us to the same [libel] standards as a newscast or you kill talk radio. If we had to qualify everything we said, talk radio would cease to exist.”

LIONEL, WABC TALK-RADIO MORNING HOST, 1999

Since the 1730s, the best defense against libel in American courts has been the truth. In most cases, if libel defendants can demonstrate that they printed or broadcast statements that were essentially true, such evidence usually bars plaintiffs from recovering any damages—even if their reputations were harmed.

In addition, there are other defenses against libel. Prosecutors, for example, who would otherwise be vulnerable to being accused of libel, are granted absolute privilege in a court of law so that they are not prevented from making accusatory statements toward defendants. The reporters who print or broadcast statements made in court are also protected against libel; they are granted conditional or qualified privilege, allowing them to report judicial or legislative proceedings even though the public statements being reported may be libelous.

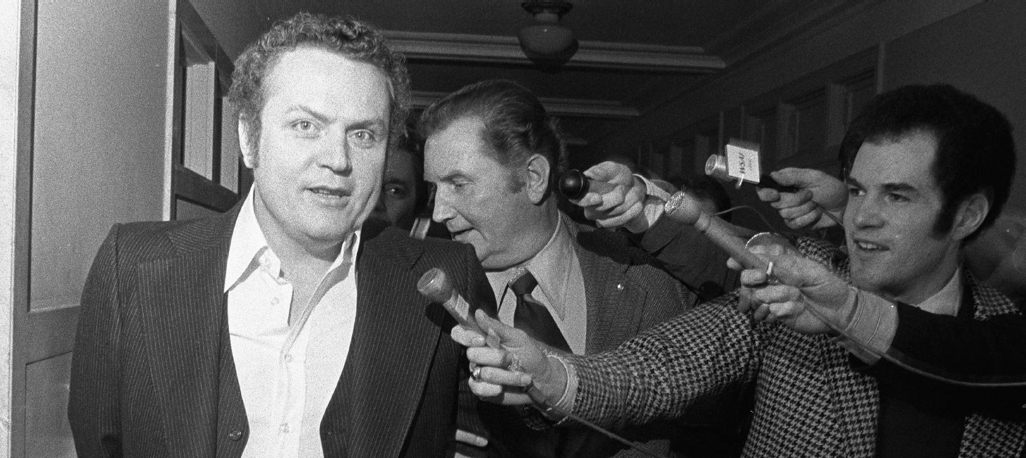

Prior to his 1984 libel trial, Hustler magazine publisher Larry Flynt was also convicted of pandering obscenity. Here, Flynt answers questions from newsmen on February 9, 1977, as he is led to jail.

Another defense against libel is the rule of opinion and fair comment. Generally, libel applies only to intentional misstatements of factual information rather than opinion, and therefore opinions are protected from libel. However, because the line between fact and opinion is often hazy, lawyers advise journalists first to set forth the facts on which a viewpoint is based and then to state their opinion based on those facts. In other words, journalists should make it clear that a statement of opinion is a criticism and not an allegation of fact.

One of the most famous tests of opinion and fair comment occurred in 1983 when Larry Flynt, publisher of Hustler magazine, published a spoof of a Campari advertisement depicting conservative minister and political activist Jerry Falwell as a drunk and as having had sexual relations with his mother. In fine print at the bottom of the page, a disclaimer read: “Ad parody—not to be taken seriously.” Often a target of Flynt’s irreverence and questionable taste, Falwell sued for libel, asking for $45 million in damages. In the verdict, the jury rejected the libel suit but found that Flynt had intentionally caused Falwell emotional distress, awarding Falwell $200,000. The case drew enormous media attention and raised concerns about the erosion of the media’s right to free speech. However, Flynt’s lawyers appealed, and in 1988 the Supreme Court unanimously overturned the verdict. Although the Court did not condone the Hustler spoof, the justices did say that the magazine was entitled to constitutional protection. In affirming Hustler’s speech rights, the Court suggested that even though parodies and insults of public figures might indeed cause emotional pain, denying the right to publish them and awarding damages for emotional reasons would violate the spirit of the First Amendment.15

Libel laws also protect satire, comedy, and opinions expressed in reviews of books, plays, movies, and restaurants. Such laws may not, however, protect malicious statements in which plaintiffs can prove that defendants used their free-speech rights to mount a damaging personal attack.

Obscenity

For most of this nation’s history, legislators have argued that obscenity does not constitute a legitimate form of expression protected by the First Amendment. The problem, however, is that little agreement has existed on how to define an obscene work. In the 1860s, a court could judge an entire book obscene if it contained a single passage believed capable of “corrupting” a person. In fact, throughout the 1800s certain government authorities outside the courts—especially U.S. post office and customs officials—held the power to censor or destroy material they deemed obscene.

“I shall not today attempt to define [obscenity]. … And perhaps I never could succeed in intelligibly doing so. But I know it when I see it.”

SUPREME COURT JUSTICE POTTER STEWART, 1964

This began to change in the 1930s during the trial involving the celebrated novel Ulysses by Irish writer James Joyce. Portions of Ulysses had been serialized in the early 1920s in an American magazine, Little Review, copies of which were later seized and burned by postal officials. The publishers of the magazine were fined $50 and nearly sent to prison. Because of the four-letter words contained in the novel and the book-burning and fining incidents, British and American publishing houses backed away from the book, and in 1928 the U.S. Customs Office officially banned Ulysses as an obscene work. Ultimately, however, Random House agreed to publish the work in the United States if it was declared “legal.” Finally, in 1933 a U.S. judge ruled that an important literary work such as Ulysses was a legitimate, protected form of expression, even if portions of the book were deemed objectionable by segments of the population.

Prince William and Catherine, Duchess of Cambridge, have been an object of ongoing fascination since marrying in 2011. The media frenzy surrounding the royal couple came to a head when the French tabloid Closer published images of what appears to be the Duchess sunbathing topless while on vacation, prompting the royal family to press criminal charges against the publication. A greater frenzy accompanied the birth of the couple’s first son in 2013. The British royal family is sadly all too familiar with the paparazzi; Prince William’s mother, Diana, Princess of Wales, died in a car accident after being chased by paparazzi in 1997.

In a landmark 1957 case, Roth v. United States, the Supreme Court offered this test of obscenity: whether to an “average person,” applying “contemporary standards,” the major thrust or theme of the material “taken as a whole” appealed to “prurient interest” (in other words, was intended to “incite lust”). By the 1960s, based on Roth, expression was not obscene if only a small part of the work lacked “redeeming social value.”

The current legal definition of obscenity derives from the 1973 Miller v. California case, which stated that to qualify as obscenity, the material must meet three criteria: (1) the average person, applying contemporary community standards, would find that the material as a whole appeals to prurient interest; (2) the material depicts or describes sexual conduct in a patently offensive way; and (3) the material, as a whole, lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value. The Miller decision contained two important ideas not present in Roth. First, it acknowledged that different communities and regions of the country have different values and standards with which to judge obscenity. Second, it required that a work be judged as a whole, so that publishers could not use the loophole of inserting a political essay or literary poem into pornographic materials to demonstrate in court that their publications contained redeeming features.

Since the Miller decision, courts have granted great latitude to printed and visual obscenity. By the 1990s, major prosecutions had become rare—aimed mostly at child pornography—as the legal system accepted the concept that a free and democratic society must tolerate even repulsive kinds of speech. Most battles over obscenity are now online, where the global reach of the Internet has eclipsed the concept of community standards. The most recent incarnation of the Child Online Protection Act—originally passed in 1998 to make it illegal to post “material that is harmful to minors”—was found unconstitutional in 2007 because it would infringe on the right to free speech on the Internet. In response to an online sexual predator case, in 2010 Massachusetts passed a law to protect children from obscene material on computers and the Internet. But a number of publishers and free speech groups argued that the law was too broad and would harm legitimate speech on the Internet. A new complication in defining pornography has emerged with cases of “sexting,” in which minors produce and send sexually graphic images of themselves via cell phones or the Internet. (See “Case Study: Is ‘Sexting’ Pornography?”.)

The Right to Privacy

“[Jailed New York Times reporter Judith Miller] does not believe, nor do we, that reporters are above the law, but instead holds that the work of journalists must be independent and free from government control if they are to effectively serve as government watchdogs.”

REPORTERS COMMITTEE FOR FREEDOM OF THE PRESS, 2005

Whereas libel laws safeguard a person’s character and reputation, the right to privacy protects an individual’s peace of mind and personal feelings. In the simplest terms, the right to privacy addresses a person’s right to be left alone, without his or her name, image, or daily activities becoming public property. Invasions of privacy occur in different situations, the most common of which are intrusion into someone’s personal space via unauthorized tape recording, photographing, wiretapping, and the like; making available to the public personal records such as health and phone records; disclosing personal information such as religion, sexual activities, or personal activities; and the unauthorized appropriation of someone’s image or name for advertising or other commercial purposes. In general, the news media have been granted wide protections under the First Amendment to do their work. For instance, the names and pictures of both private individuals and public figures can usually be used without their consent in most news stories. Additionally, if private citizens become part of public controversies and subsequent news stories, the courts have usually allowed the news media to treat them like public figures (i.e., record their quotes and use their images without the individuals’ permission). The courts have even ruled that accurate reports of criminal and court records, including the identification of rape victims, do not normally constitute privacy invasions. Nevertheless, most newspapers and broadcast outlets use their own internal guidelines and ethical codes to protect the privacy of victims and defendants, especially in cases involving rape and child abuse.

Public figures have received some legal relief as many local municipalities and states have passed “anti-paparazzi” laws that protect individuals from unwarranted scrutiny and surveillance of personal activities on private property or outside public forums. Some courts have ruled that photographers must keep a certain distance away from celebrities, although powerful zoom lens technology usually overcomes this obstacle. However, every year brings a few stories of a Hollywood actor or sports figure punching a tabloid photographer or TV cameraman who got too close. And in 2004, the Supreme Court ruled—as an exception to the Freedom of Information Act—that families of prominent figures who have died have the right to object to the release of autopsy photos, so that the images may not be exploited.

A number of laws also protect the privacy of regular citizens. For example, the Privacy Act of 1974 protects individuals’ records from public disclosure unless individuals give written consent. The Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986 extended the law to computer-stored data and the Internet, although subsequent court decisions ruled that employees have no privacy rights in electronic communications conducted on their employer’s equipment. The USA PATRIOT Act of 2001, however, weakened the earlier laws and gave the federal government more latitude in searching private citizens’ records and intercepting electronic communications without a court order.