Culture as a Map

The second way to view culture is as a map. Here, culture is an ongoing and complicated process—rather than a high/low vertical hierarchy—that allows us to better account for our diverse and individual tastes. In the map model, we judge forms of culture as good or bad based on a combination of personal taste and the aesthetic judgments a society makes at particular historical times. Because such tastes and evaluations are “all over the map,” a cultural map suggests that we can pursue many connections from one cultural place to another and can appreciate a range of cultural experiences without simply ranking them from high to low.

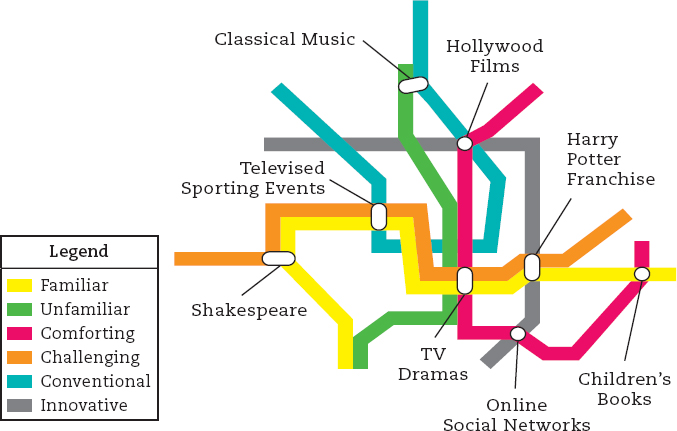

Our attraction to and choice of cultural phenomena—such as the stories we read in books or watch at the movies—represent how we make our lives meaningful. Culture offers plenty of places to go that are conventional, familiar, and comforting. Yet at the same time, our culture’s narrative storehouse contains other stories that tend toward the innovative, unfamiliar, and challenging. Most forms of culture, however, demonstrate multiple tendencies. We may use online social networks because they are both comforting (an easy way to keep up with friends) and innovative (new tools or apps that engage us). We watch televised sporting events for their familiarity and conventional organization, and because the unknown outcome can be unpredictable or challenging. The map offered here (see Figure 1.3) is based on a familiar subway grid. Each station represents tendencies or elements related to why a person may be attracted to different cultural products. Also, more popular culture forms congregate in more congested areas of the map, while less popular cultural forms are outliers. Such a large, multidirectional map may be a more flexible, multidimensional, and inclusive way of imagining how culture works.

The Comfort of Familiar Stories

The appeal of culture is often its familiar stories, pulling audiences toward the security of repetition and common landmarks on the cultural map. Consider, for instance, early television’s Lassie series, about the adventures of a collie named Lassie and her owner, young Timmy. Of the more than five hundred episodes, many have a familiar and repetitive plot line: Timmy, who arguably possessed the poorest sense of direction and suffered more concussions than any TV character in history, gets lost or knocked unconscious. After finding Timmy and licking his face, Lassie goes for help and saves the day. Adult critics might mock this melodramatic formula, but many children find comfort in the predictability of the story. This quality is also evident when night after night children ask their parents to read them the same book, such as Margaret Wise Brown’s Good Night, Moon or Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are, or watch the same DVD, such as Snow White or The Princess Bride.

Innovation and the Attraction of “What’s New”

Like children, adults also seek comfort, often returning to an old Beatles or Guns N’ Roses song, a William Butler Yeats or Emily Dickinson poem, or a TV rerun of Seinfeld or Andy Griffith. But we also like cultural adventure. We may turn from a familiar film on cable’s American Movie Classics to discover a new movie from Iran or India on the Independent Film Channel. We seek new stories and new places to go—those aspects of culture that demonstrate originality and complexity. For instance, James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake (1939) created language anew and challenged readers, as the novel’s poetic first sentence illustrates: “riverrun, past Eve and Adam’s, from swerve of shore to bend of bay, brings us by a commodius vicus of recirculation back to Howth Castle and Environs.” A revolutionary work, crammed with historical names and topical references to events, myths, songs, jokes, and daily conversation, Joyce’s novel remains a challenge to understand and decode. His work demonstrated that part of what culture provides is the impulse to explore new places, to strike out in new directions, searching for something different that may contribute to growth and change.

A Wide Range of Messages

We know that people have complex cultural tastes, needs, and interests based on different backgrounds and dispositions. It is not surprising, then, that our cultural treasures, from blues music and opera to comic books and classical literature, contain a variety of messages. Just as Shakespeare’s plays—popular entertainments in his day—were packed with both obscure and popular references, TV episodes of The Simpsons have included allusions to the Beatles, Kafka, Teletubbies, Tennessee Williams, talk shows, Aerosmith, Star Trek, The X-Files, Freud, Psycho, and Citizen Kane. In other words, as part of an ongoing process, cultural products and their meanings are “all over the map,” spreading out in diverse directions.

Challenging the Nostalgia for a Better Past

In this map model, culture is not ranked as high or low. Instead, the model shows culture as spreading out in several directions across a variety of dimensions. For example, some cultural forms can be familiar, innovative, and challenging like the Harry Potter books and movies. This model accounts for the complexity of individual tastes and experiences. The map model also suggests that culture is a process by which we produce meaning—i.e., make our lives meaningful—as well as a complex collection of media products and texts. The map shown is just one interpretation of culture. What cultural products would you include in your own model? What dimensions would you link to and why?

Some critics of popular culture assert—often without presenting supportive evidence—that society was better off before the latest developments in mass media. These critics resist the idea of reimagining an established cultural hierarchy as a multidirectional map. The nostalgia for some imagined “better past” has often operated as a device for condemning new cultural phenomena. This impulse to criticize something that is new is often driven by fear of change or of cultural differences. Back in the nineteenth century, in fact, a number of intellectuals and politicians worried that rising literacy rates among the working class might create havoc: How would the aristocracy and intellectuals maintain their authority and status if everyone could read? A recent example includes the fear that some politicians, religious leaders, and citizens have expressed about the legalization of same-sex marriage, claiming that it would violate older religious tenets or the sanctity of past traditions.

Throughout history, a call to return to familiar terrain, to “the good old days,” has been a frequent response to new, “threatening” forms of popular culture or to any ideas that are different from what we already believe. Yet over the years many of these forms, including the waltz, silent movies, ragtime, and jazz, have themselves become cultural “classics.” How can we tell now what the future has in store for such cultural expressions as rock and roll, soap operas, fashion photography, dance music, hip-hop, tabloid newspapers, graphic novels, reality TV, and social media?