Shifting Values in Postmodern Culture

For many people, the changes occurring in the postmodern period—from roughly the mid-twentieth century to today—are identified by a confusing array of examples: music videos, remote controls, Nike ads, shopping malls, fax machines, e-mail, video games, blogs, USA Today, YouTube, iPads, hip-hop, and reality TV (see Table 1.1). Some critics argue that postmodern culture represents a way of seeing—a new condition, or even a malady, of the human spirit. Although there are many ways to define the postmodern, this textbook focuses on four major features or values that resonate best with changes across media and culture: populism, diversity, nostalgia, and paradox.

As a political idea, populism tries to appeal to ordinary people by highlighting or even creating an argument or conflict between “the people” and “the elite.” In virtually every campaign, populist politicians often tell stories and run ads that criticize big corporations and political favoritism. Meant to resonate with middle-class values and regional ties, such narratives generally pit Southern or Midwestern small-town “family values” against the supposedly coarser, even corrupt, urban lifestyles associated with big cities like Washington or Los Angeles.

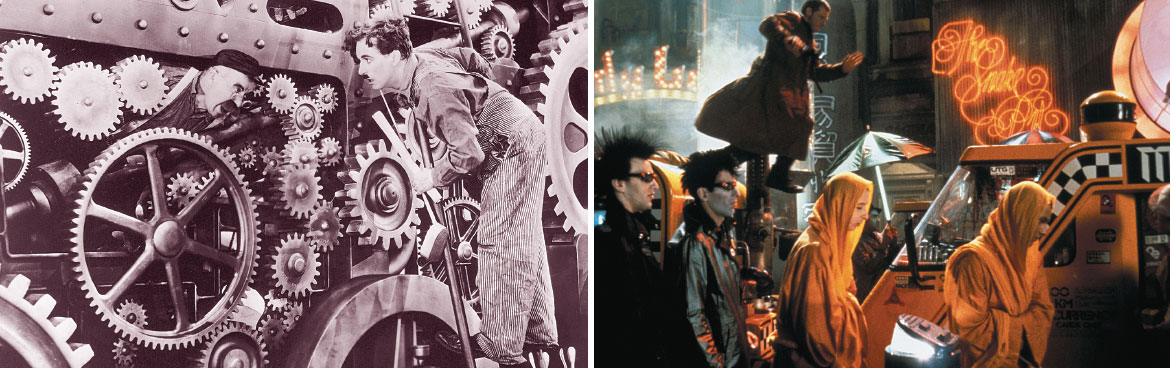

In postmodern culture, populism has manifested itself in many ways. For example, artists and performers, like Chuck Berry in “Roll Over Beethoven” (1956) or Queen in “Bohemian Rhapsody” (1975), intentionally blurred the border between high and low culture. In the visual arts, following Andy Warhol’s 1960s pop art style, advertisers have borrowed from both fine art and street art, while artists appropriated styles from commerce and popular art. Film stars, like Angelina Jolie and Ben Affleck, often champion oppressed groups while appearing in movies that make the actors wealthy global icons of consumer culture.

TABLE 1.1

TRENDS ACROSS HISTORICAL PERIODS

| Trend | Premodern (pre-1800s) | Modern Industrial Revolution (1800s–1950s) | Postmodern (1950s–present) |

| Work hierarchies | peasants / merchants / rulers | factory workers/managers / national CEOs | temp workers / global CEOs |

| Major work sites | field / farm | factory / office | office / home/”virtual” or mobile office |

| Communication reach | local | national | global |

| Communication transmission | oral / manuscript | print / electronic | electronic / digital |

| Communication channels | storytellers / elders / town criers | books / newspapers / magazines / radio | television / cable / Internet / multimedia |

| Communication at home | quill pen | typewriter / office computer | personal computer / laptop / smartphone / social networks |

| Key social values | belief in natural or divine order | individualism / rationalism / efficiency / antitradition | antihierarchy / skepticism (about science, business, government, etc) / diversity / multiculturalism / irony & paradox |

| Journalism | oral & print-based/partisan/controlled by political parties | print-based / ”objective” / efficient / timely / controlled by publishing families | TV & Internet±based / opinionated / conversational / controlled by global entertainment conglomerates |

Other forms of postmodern style blur modern distinctions not only between art and commerce but also between fact and fiction. For example, television vocabulary now includes infotainment (Entertainment Tonight, Access Hollywood) and infomercials (such as fading celebrities selling antiwrinkle cream). On cable, MTV’s reality programs—such as Real World and Jersey Shore—blur boundaries between the staged and the real, mixing serious themes with comedic interludes and romantic entanglements; Comedy Central’s fake news programs, The Daily Show with Jon Stewart and The Colbert Report, combine real, insightful news stories with biting satires of traditional broadcast and cable news programs.

Closely associated with populism, another value (or vice) of the postmodern period emphasizes diversity and fragmentation, including the wild juxtaposition of old and new cultural styles. In a suburban shopping mall, for instance, Gap stores border a food court with Vietnamese, Italian, and Mexican options, while techno-digitized instrumental versions of 1960s protest music play in the background to accompany shoppers. Part of this stylistic diversity involves borrowing and transforming earlier ideas from the modern period. In music, hip-hop deejays and performers sample old R&B, soul, and rock classics, both reinventing old songs and creating something new. Critics of postmodern style contend that such borrowing devalues originality, emphasizing surface over depth and recycled ideas over new ones. Throughout the twentieth century, for example, films were adapted from books and short stories. More recently, films often derive from old popular TV series: Mission Impossible, Charlie’s Angels, and The A-Team, to name just a few. Video games like the Resident Evil franchise and Tomb Raider have been made into Hollywood blockbusters. In fact, by 2012 more than twenty-five video games, including BioShock and the Warcraft series, were in various stages of film production.

Another tendency of postmodern culture involves rejecting rational thought as “the answer” to every social problem, reveling instead in nostalgia for the premodern values of small communities, traditional religion, and even mystical experience. Rather than seeing science purely as enlightened thinking or rational deduction that relies on evidence, some artists, critics, and politicians criticize modern values for laying the groundwork for dehumanizing technological advances and bureaucratic problems. For example, in the renewed debates over evolution, one cultural narrative that plays out often pits scientific evidence against religious belief and literal interpretations of the Bible. And in popular culture, many TV programs—such as The X-Files, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Charmed, Angel, Lost, and Fringe—emerged to offer mystical and supernatural responses to the “evils” of our daily world and the limits of science and the purely rational.

In the 2012 presidential campaign, this nostalgia for the past was frequently deployed as a narrative device, with the Republican candidates depicting themselves as protectors of tradition and small-town values, and juxtaposing themselves against President Obama’s messages of change and progressive reform. In fact, after winning the Nevada Republican primary in 2012, former Massachusetts governor Mitt Romney framed the story this way: “President Obama says he wants to fundamentally transform America. We [Romney and his supporters] want to restore to America the founding principles that made the country great.” By portraying change—and present conditions—as sinister forces that could only be overcome by returning to some point in the past when we were somehow “better,” Romney laid out what he saw as the central narrative conflicts of the 2012 presidential campaign: tradition versus change, and past versus present.

Lastly, the fourth aspect of our postmodern time is the willingness to accept paradox. While modern culture emphasized breaking with the past in the name of progress, postmodern culture stresses integrating—or converging—retro beliefs and contemporary culture. So at the same time that we seem nostalgic for the past, we embrace new technologies with a vengeance. For example, fundamentalist religious movements that promote seemingly outdated traditions (e.g., rejecting women’s rights to own property or seek higher education) still embrace the Internet and modern technology as recruiting tools or as channels for spreading messages. Culturally conservative politicians, who seem most comfortable with the values of the 1950s nuclear family, welcome talk shows, Twitter, Facebook, and Internet and social media ad campaigns as venues to advance their messages and causes.

Although new technologies can isolate people or encourage them to chase their personal agendas (e.g., a student perusing his individual interests online), as modernists warned, new technologies can also draw people together to advance causes or to solve community problems or to discuss politics on radio talk shows, on Facebook, or on smartphones. For example, in 2011 and 2012 Twitter made the world aware of protesters in many Arab nations, including Egypt and Libya, when governments there tried to suppress media access. Our lives today are full of such incongruities.