Battles in Rock and Roll

The blurring of racial lines and the breakdown of other conventional boundaries meant that performers and producers were forced to play a tricky game to get rock and roll accepted by the masses. Two prominent white disc jockeys used different methods. Cleveland deejay Alan Freed, credited with popularizing the term rock and roll, played original R&B recordings from the race charts and black versions of early rock and roll on his program. In contrast, Philadelphia deejay Dick Clark believed that making black music acceptable to white audiences required cover versions by white artists. By the mid-1950s, rock and roll was gaining acceptance with the masses, but rock-and-roll artists and promoters still faced further obstacles: Black artists found that their music was often undermined by white cover versions; the payola scandals portrayed rock and roll as a corrupt industry; and fears of rock and roll as a contributing factor in juvenile delinquency resulted in censorship.

White Cover Music Undermines Black Artists

By the mid-1960s, black and white artists routinely recorded and performed one another’s original tunes. For example, established black R&B artist Otis Redding covered the Rolling Stones’ “Satisfaction” and Jimi Hendrix covered Bob Dylan’s “All along the Watchtower,” while just about every white rock-and-roll band established its career by covering R&B classics. Most notably, the Beatles covered “Twist and Shout” and “Money” and the Rolling Stones—whose name came from a Muddy Waters song—covered numerous Robert Johnson songs and other blues staples.

Although today we take such rerecordings for granted, in the 1950s the covering of black artists’ songs by white musicians was almost always an attempt to capitalize on popular songs from the R&B “race” charts and transform them into hits on the white pop charts. Often, white producers would not only give co-writing credit to white performers for the tunes they only covered, but they would also buy the rights to potential hits from black songwriters who seldom saw a penny in royalties or received songwriting credit.

During this period, black R&B artists, working for small record labels, saw many of their popular songs covered by white artists working for major labels. These cover records, boosted by better marketing and ties to white deejays, usually outsold the original black versions. For instance, the 1954 R&B song “Sh-Boom,” by the Chords on Atlantic’s Cat label, was immediately covered by a white group, the Crew Cuts, for the major Mercury label. Record sales declined for the Chords, although jukebox and R&B radio play remained strong for their original version. By 1955, R&B hits regularly crossed over to the pop charts, but inevitably the cover music versions were more successful. Pat Boone’s cover of Fats Domino’s “Ain’t That a Shame” went to No. 1 and stayed on the Top 40’s pop chart for twenty weeks, whereas Domino’s original made it only to No. 10. During this time, Pat Boone ranked as the king of cover music, with thirty-eight Top 40 songs between 1955 and 1962. His records were second in sales only to Elvis Presley’s. Slowly, however, the cover situation changed. After watching Boone outsell his song “Tutti-Frutti” in 1956, Little Richard wrote “Long Tall Sally,” which included lyrics written and delivered in such a way that he believed Boone would not be able to adequately replicate them. “Long Tall Sally” went to No. 6 for Little Richard and charted for twelve weeks; Boone’s version got to No. 8 and stayed there for nine weeks.

Overt racism lingered in the music business well into the 1960s. A turning point, however, came in 1962, the last year that Pat Boone, then age twenty-eight, ever had a Top 40 rock-and-roll hit. That year, Ray Charles covered “I Can’t Stop Loving You,” a 1958 country song by the Grand Ole Opry’s Don Gibson. This marked the first time that a black artist, covering a white artist’s song, had notched a No. 1 pop hit. With Charles’s cover, the rock-and-roll merger between gospel and R&B, on one hand, and white country and pop, on the other, was complete. In fact, the relative acceptance of black crossover music provided a more favorable cultural context for the political activism that spurred important Civil Rights legislation in the mid-1960s.

Payola Scandals Tarnish Rock and Roll

The payola scandals of the 1950s were another cloud over rock-and-roll music and its artists. In the music industry, payola is the practice of record promoters paying deejays or radio programmers to play particular songs. As recorded rock and roll became central to commercial radio’s success in the 1950s and the demand for airplay grew enormous, independent promoters hired by record labels used payola to pressure deejays into playing songs by the artists they represented.

Although payola was considered a form of bribery, no laws prohibited its practice. However, following closely on the heels of television’s quiz-show scandals (see Chapter 6), congressional hearings on radio payola began in December 1959. The hearings were partly a response to generally fraudulent business practices, but they were also an opportunity to blame deejays and radio for rock and roll’s negative impact on teens by portraying it as a corrupt industry.

The payola scandals threatened, ended, or damaged the careers of a number of rock-and-roll deejays and undermined rock and roll’s credibility for a number of years. In 1959, shortly before the hearings, Chicago deejay Phil Lind decided to clear the air. He broadcast secretly taped discussions in which a representative of a small independent record label acknowledged that it had paid $22,000 to ensure that a record would get airplay. Lind received calls threatening his life and had to have police protection. At the hearings in 1960, Alan Freed admitted to participating in payola, although he said he did not believe there was anything illegal about such deals, and his career soon ended. Dick Clark, then an influential deejay and the host of TV’s American Bandstand, would not admit to participating in payola. But the hearings committee chastised Clark and alleged that some of his complicated business deals were ethically questionable, a censure that hung over him for years. Congress eventually added a law concerning payola to the Federal Communications Act, prescribing a $10,000 fine and/or a year in jail for each violation (see Chapter 5).

Fears of Corruption Lead to Censorship

Since rock and roll’s inception, one of the uphill battles it faced was the perception that it was a cause of juvenile delinquency, which was statistically on the rise in the 1950s. Looking for an easy culprit rather than considering contributing factors such as neglect, the rising consumer culture, or the growing youth population, many assigned blame to rock and roll. The view that rock and roll corrupted youth was widely accepted by social authorities, and rock-and-roll music was often censored, eventually even by the industry itself.

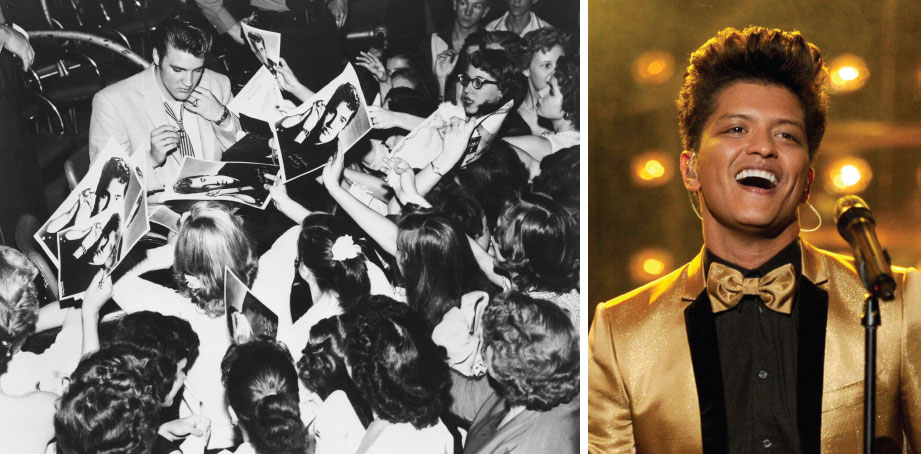

By late 1959, many key figures in rock and roll had been tamed. Jerry Lee Lewis was exiled from the industry, labeled southern “white trash” for marrying his thirteen-year-old third cousin; Elvis Presley, having already been censored on television, was drafted into the army; Chuck Berry was run out of Mississippi and eventually jailed for gun possession and transporting a minor across state lines; and Little Richard felt forced to tone down his image and left rock and roll to sing gospel music. A tragic accident led to the final taming of rock and roll’s first frontline. In February 1959, Buddy Holly (“Peggy Sue”), Ritchie Valens (“La Bamba”), and the Big Bopper (“Chantilly Lace”) all died in an Iowa plane crash—a tragedy mourned in Don McLean’s 1971 hit “American Pie” as “the day the music died.”

Although rock and roll did not die in the late 1950s, the U.S. recording industry decided that it needed a makeover. To protect the enormous profits the new music had been generating, record companies began to discipline some of rock and roll’s rebellious impulses. In the early 1960s, the industry introduced a new generation of clean-cut white singers, like Frankie Avalon, Connie Francis, Ricky Nelson, Lesley Gore, and Fabian. Rock and roll’s explosive violations of racial, class, and other boundaries were transformed into simpler generation gap problems, and the music developed a milder reputation.