Music Labels Influence the Industry

After several years of steady growth, revenues for the recording industry experienced significant losses beginning in 2000 as file–sharing began to undercut CD sales. By 2011, U.S. music sales were $7 billion, up for the first time since 2004, but down from a peak of $14.5 billion in 1999. The U.S. market accounts for about one-third of global sales, followed by Japan, the United Kingdom, France, Germany, and Canada. Despite the losses, the U.S. and global music business still constitutes a powerful oligopoly: a business situation in which a few firms control most of an industry’s production and distribution resources. This global reach gives these firms enormous influence over what types of music gain worldwide distribution and popular acceptance.

Fewer Major Labels Control More Music

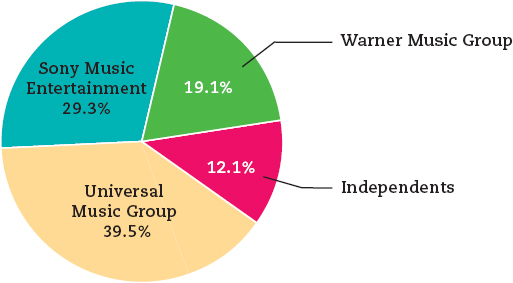

From the 1950s through the 1980s, the music industry, though powerful, consisted of a large number of competing major labels, along with numerous independent labels. Over time, the major labels began swallowing up the independents and then buying one another. By 1998, only six major labels remained—Universal, Warner, Sony, BMG, EMI, and Polygram. That year, Universal acquired Polygram, and in 2003 BMG and Sony merged. (BMG left the partnership in 2008.) In 2012, Universal gained regulatory approval to purchase EMI’s recorded music division. Now, only three major music corporations remain: Universal Music Group, Sony Music Entertainment, and Warner Music Group. Together, these companies control nearly 90 percent of the recording industry market in the United States (see Figure 4.2). Although their revenue has eroded over the past decade, the major music corporations still wield great power, as they can control when and how their artists’ music will be licensed to play on new distribution services.

Source: Nielsen SoundScan, 2012.

Note: FIGURE combines UMG’s and EMI’s premerger market shares.

The Indies Spot the Trends

The rise of rock and roll in the 1950s and early 1960s showcased a rich diversity of independent labels—including Sun, Stax, Chess, and Motown—all vying for a share of the new music. That tradition lives on today. In contrast to the three global players, some five thousand large and small independent production houses—or indies—record less commercially viable music, or music they hope will become commercially viable. Often struggling enterprises, indies require only a handful of people to operate them. Producing between 11 and 15 percent of America’s music, indies often depend on wholesale distributors to promote and sell their music, or enter into deals with majors to gain wider distribution for their artists. The Internet has also become a low-cost distribution outlet for independent labels, which sell recordings and merchandise and list tour schedules online. (See “Alternative Voices”.)

Indies play a major role as the music industry’s risk-takers, since major labels are reluctant to invest in commercially unproven artists. The majors frequently rely on indies to discover and initiate distinctive musical trends that first appear on a local level. For instance, indies such as Sugarhill, Tommy Boy, and Uptown emerged in the 1980s to produce regional hip-hop. In the early 2000s, bands of the “indie-rock” movement, such as Yo La Tengo and Arcade Fire, found their home on indie labels Matador and Merge. Once indies become successful, the financial inducement to sell out to a major label is enormous. Seattle indie Sub Pop (Nirvana’s initial recording label) sold 49 percent of its stock to Time Warner for $20 million in 1994. However, the punk label Epitaph rejected takeover offers as high as $50 million in the 1990s and remains independent. All the major labels look for and swallow up independent labels that have successfully developed artists with national or global appeal.