The Golden Age of Radio

“There are three things which I shall never forget about America—the Rocky Mountains, Niagara Falls, and Amos ‘n’ Andy.”

GEORGE BERNARD SHAW, IRISH PLAYWRIGHT

Many programs on television today were initially formulated for radio. The first weather forecasts and farm reports on radio began in the 1920s. Regularly scheduled radio news analysis started in 1927, with H. V. Kaltenborn, a reporter for the Brooklyn Eagle, providing commentary on AT&T’s WEAF. The first regular network news analysis began on CBS in 1930, featuring Lowell Thomas, who would remain on radio for forty-four years.

Early Radio Programming

Early on, only a handful of stations operated in most large radio markets, and popular stations were affiliated with CBS, NBC-Red, or NBC-Blue. Many large stations employed their own in-house orchestras and aired live music daily. Listeners had favorite evening programs, usually fifteen minutes long, to which they would tune in each night. Families gathered around the radio to hear such shows as Amos ‘n’ Andy, The Shadow, The Lone Ranger, The Green Hornet, and Fibber McGee and Molly, or one of President Franklin Roosevelt’s fireside chats.

Among the most popular early programs on radio, the variety show was the forerunner to popular TV shows like the Ed Sullivan Show. The variety show, developed from stage acts and vaudeville, began with the Eveready Hour in 1923 on WEAF. Considered experimental, the program presented classical music, minstrel shows, comedy sketches, and dramatic readings. Stars from vaudeville, musical comedy, and New York theater and opera would occasionally make guest appearances.

By the 1930s, studio-audience quiz shows—Professor Quiz and the Old Time Spelling Bee—had emerged. Other quiz formats, used on Information Please and Quiz Kids, featured guest panelists. The quiz formats were later copied by television, particularly in the 1950s. Truth or Consequences, based on a nineteenth-century parlor game, first aired on radio in 1940 and featured guests performing goofy stunts. It ran for seventeen years on radio and another twenty-seven on television, influencing TV stunt shows like CBS’s Beat the Clock in the 1950s and NBC’s Fear Factor in the early 2000s.

Dramatic programs, mostly radio plays that were broadcast live from theaters, developed as early as 1922. Historians mark the appearance of Clara, Lu, and Em on WGN in 1931 as the first One year later, Colgate-Palmolive bought the program, put it on NBC, and began selling the soap products that gave this dramatic genre its distinctive nickname. Early “soaps” were fifteen minutes in length and ran five or six days a week. By 1940, sixty different soap operas occupied nearly eighty hours of network radio time each week.

Most radio programs had a single sponsor that created and produced each show. The networks distributed these programs live around the country, charging the sponsors advertising fees. Many shows—the Palmolive Hour, General Motors Family Party, the Lucky Strike Orchestra, and the Eveready Hour among them—were named after the sole sponsor’s product.

Radio Programming as a Cultural Mirror

The situation comedy, a major staple of TV programming today, began on radio in the mid-1920s. By the early 1930s, the most popular comedy was Amos ‘n’ Andy, which started on Chicago radio in 1925 before moving to NBC-Blue in 1929. Amos ‘n’ Andy was based on the conventions of the nineteenth-century minstrel show and featured black characters stereotyped as shiftless and stupid. Created as a blackface stage act by two white comedians, Charles Correll and Freeman Gosden, the program was criticized as racist. But NBC and the program’s producers claimed that Amos ‘n’ Andy was as popular among black audiences as among white listeners.10

Amos ‘n’ Andy also launched the idea of the serial show: a program that featured continuing story lines from one day to the next. The format was soon copied by soap operas and other radio dramas. The show aired six nights a week from 7:00 to 7:15 P.M. During the show’s first year on the network, radio-set sales rose nearly 25 percent nationally. To keep people coming to restaurants and movie theaters, owners broadcast Amos ‘n’ Andy in lobbies, rest rooms, and entryways. Early radio research estimated that the program aired in more than half of all radio homes in the nation during the 1930–31 season, making it the most popular radio series in history. In 1951, it made a brief transition to television (Correll and Gosden sold the rights to CBS for $1 million), becoming the first TV series to have an entirely black cast. But amid a strengthening Civil Rights movement and a formal protest by the NAACP (which argued that “every character is either a clown or a crook”), CBS canceled the program in 1953.11

The Authority of Radio

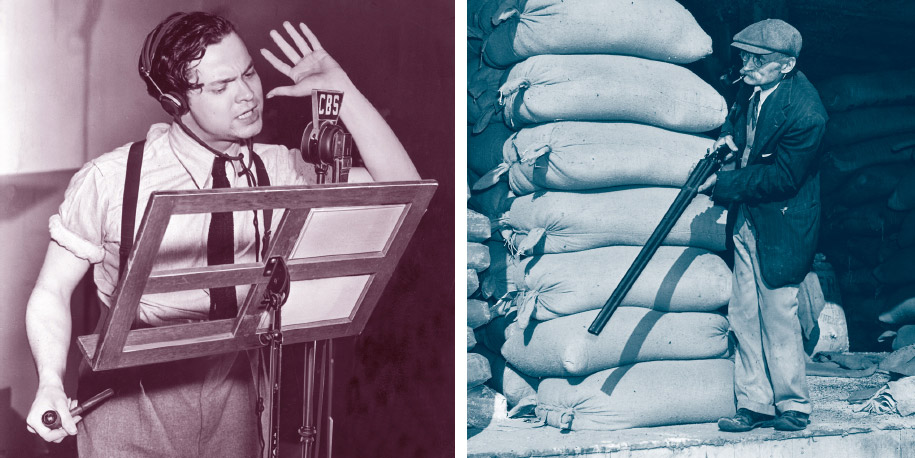

The most famous single radio broadcast of all time was an adaptation of H. G. Wells’s War of the Worlds on the radio series Mercury Theater of the Air. Orson Welles produced, hosted, and acted in this popular series, which adapted science fiction, mystery, and historical adventure dramas for radio. On Halloween eve in 1938, the twenty-three-year-old Welles aired the 1898 Martian invasion novel in the style of a radio news program. For people who missed the opening disclaimer, the program sounded like a real news report, with eyewitness accounts of battles between Martian invaders and the U.S. Army.

The program created a panic that lasted several hours. In New Jersey, some people walked through the streets with wet towels around their heads for protection from deadly Martian heat rays. In New York, young men reported to their National Guard headquarters to prepare for battle. Across the nation, calls jammed police switchboards. Afterward, Orson Welles, once the radio voice of The Shadow, used the notoriety of this broadcast to launch a film career. Meanwhile, the FCC called for stricter warnings both before and during programs that imitated the style of radio news.