The FM Revolution and Edwin Armstrong

By the time the broadcast industry launched commercial television in the 1950s, many people, including David Sarnoff of RCA, were predicting radio’s demise. To fund television’s development and to protect his radio holdings, Sarnoff had even delayed a dramatic breakthrough in broadcast sound, what he himself called a “revolution”—FM radio.

Source: Adapted from David Cheshire, The Video Manual, 1982.

Edwin Armstrong, who first discovered and developed FM radio in the 1920s and early 1930s, is often considered the most prolific and influential inventor in radio history. He used De Forest’s vacuum tube to invent an amplifying system that enabled radio receivers to pick up distant signals, rendering the enormous alternators used for generating power in early radio transmitters obsolete. In 1922, he sold a “super” version of his circuit to RCA for $200,000 and sixty thousand shares of RCA stock, which made him a millionaire as well as RCA’s largest private stockholder.

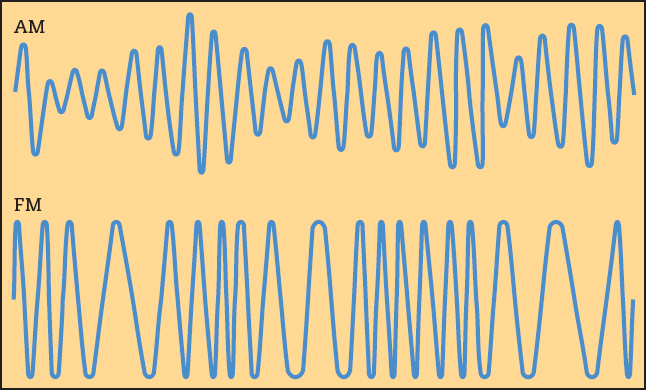

Armstrong also worked on the major problem of radio reception—electrical interference. Between 1930 and 1933, the inventor filed five patents on FM, or frequency modulation. Offering static-free radio reception, FM supplied greater fidelity and clarity than AM, making FM ideal for music. AM, or amplitude modulation (modulation refers to the variation in waveforms), stressed the volume, or height, of radio waves; FM accentuated the pitch, or distance, between radio waves (see Figure 5.2).

Although David Sarnoff, the president of RCA, thought that television would replace radio, he helped Armstrong set up the first experimental FM station atop the Empire State Building in New York City. Eventually, though, Sarnoff thwarted FM’s development (which he was able to do because RCA had an option on Armstrong’s new patents). Instead, in 1935 Sarnoff threw RCA’s considerable weight behind the development of television. With the FCC allocating and reassigning scarce frequency spaces, RCA wanted to ensure that channels went to television before they went to FM. But most of all, Sarnoff wanted to protect RCA’s existing AM empire. Given the high costs of converting to FM and the revenue needed for TV experiments, Sarnoff decided to close down Armstrong’s station.

Armstrong forged ahead without RCA. He founded a new FM station and advised other engineers, who started more than twenty experimental stations between 1935 and the early 1940s. In 1941, the FCC approved limited space allocations for commercial FM licenses. During the next few years, FM grew in fits and starts. Between 1946 and early 1949, the number of commercial FM stations expanded from 48 to 700. But then the FCC moved FM’s frequency space to a new band on the electromagnetic spectrum, rendering some 400,000 prewar FM receiver sets useless. FM’s future became uncertain, and by 1954 the number of FM stations had fallen to 560.

On January 31, 1954, Edwin Armstrong, weary from years of legal skirmishes over patents with RCA, Lee De Forest, and others, wrote a note apologizing to his wife, removed the air conditioner from his thirteenth-story New York apartment window, and jumped to his death. A month later, David Sarnoff announced record profits of $850 million for RCA, with TV sales accounting for 54 percent of the company’s earnings. In the early 1960s, the FCC opened up more spectrum space for the superior sound of FM, infusing new life into radio.

Although AM stations had greater reach, they could not match the crisp fidelity of FM, which made FM preferable for music. In the early 1970s, about 70 percent of listeners tuned almost exclusively to AM radio. By the 1980s, however, FM had surpassed AM in profitability. By the 2010s, more than 75 percent of all listeners preferred FM, and about 6,660 commercial and about 4,000 educational FM stations were in operation. The expansion of FM represented one of the chief ways radio survived television and Sarnoff’s gloomy predictions.