The Rise of Format and Top 40 Radio

Live and recorded music had long been radio’s single biggest staple, accounting for 48 percent of all programming in 1938. Although live music on radio was generally considered superior to recorded music, early disc jockeys made a significant contribution to the latter. They demonstrated that music alone could drive radio. In fact, when television snatched radio’s program ideas and national sponsors, radio’s dependence on recorded music became a necessity and helped the medium survive the 1950s.

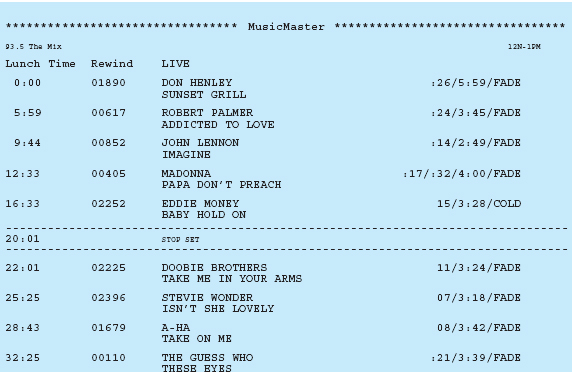

Source: KCVM, Cedar Falls, IA, 2010.

As early as 1949, station owner Todd Storz in Omaha, Nebraska, experimented with formula-driven radio, or format radio. Under this system, management rather than deejays controlled programming each hour. When Storz and his program manager noticed that bar patrons and waitresses repeatedly played certain favorite songs from the forty records available in a jukebox, they began researching record sales to identify the most popular tunes. From observing jukebox culture, Storz hit on the idea of rotation: playing the top songs many times during the day. By the mid-1950s, the management-control idea combined with the rock-and-roll explosion, and the Top 40 format was born. Although the term Top 40 derived from the number of records stored in a jukebox, this format came to refer to the forty most popular hits in a given week as measured by record sales.

As format radio grew, program managers combined rapid deejay chatter with the best-selling songs of the day and occasional oldies—popular songs from a few months earlier. By the early 1960s, to avoid “dead air,” managers asked deejays to talk over the beginning and the end of a song so that listeners would feel less compelled to switch stations. Ads, news, weather forecasts, and station identifications were all designed to fit a consistent station environment. Listeners, tuning in at any moment, would recognize the station by its distinctive sound.

In format radio, management carefully coordinates, or programs, each hour, dictating what the deejay will do at various intervals throughout each hour of the day (see Figure 5.3). Management creates a program log—once called a hot clock in radio jargon—that deejays must follow. By the mid-1960s, one study had determined that in a typical hour on Top 40, listeners could expect to hear about twenty ads; numerous weather, time, and contest announcements; multiple recitations of the station’s call letters; about three minutes of news; and approximately twelve songs.

Radio managers further sectioned off programming into day parts, which typically consisted of time blocks covering 6 to 10 A.M., 10 A.M. to 3 P.M., 3 to 7 P.M., and 7 P.M. to midnight. Each day part, or block, was programmed through ratings research according to who was listening. For instance, a Top 40 station would feature its top deejays in the morning and afternoon periods when audiences, many riding in cars, were largest. From 10 A.M. to 3 P.M., research determined that women at home and secretaries at work usually controlled the dial, so program managers, capitalizing on the gender stereotypes of the day, played more romantic ballads and less hard rock. Teenagers tended to be heavy evening listeners, so program managers often discarded news breaks at this time, since research showed that teens turned the dial when news came on.

Critics of format radio argued that only the top songs received play and that lesser-known songs deserving air time received meager attention. Although a few popular star deejays continued to play a role in programming, many others quit when managers introduced formats. Owners approached programming as a science, but deejays considered it an art form. Program managers argued that deejays had different tastes from those of the average listener and therefore could not be fully trusted to know popular audience tastes. The owners’ position, which generated more revenue, triumphed.