Radio and Convergence

Like every other mass medium, radio is moving into the future by converging with the Internet. Interestingly, this convergence is taking radio back to its roots in some aspects. Internet radio allows for much more variety in radio, which is reminiscent of radio’s earliest years when nearly any individual or group with some technical skill could start a radio station. Moreover, podcasts bring back content like storytelling, instructional programs, and local topics of interest that have largely been missing in corporate radio. And portable listening devices like the iPod and radio apps for the iPad and smartphones harken back to the compact portability that first came with the popularization of transistor radios in the 1950s.

Internet Radio

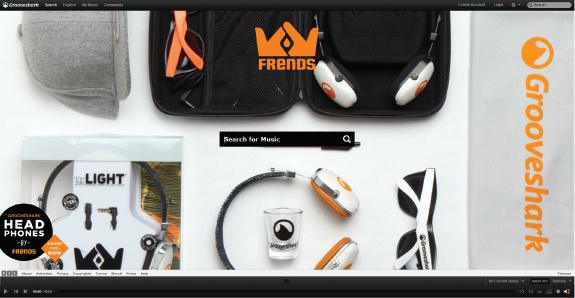

Internet radio emerged in the 1990s with the popularity of the Web. Internet radio stations come in two types. The first involves an existing AM, FM, satellite, or HD station “streaming” a simulcast version of its on-air signal over the Web. According to the Arbitron radio rating service, more than 9,000 radio stations stream their programming over the Web today.12 Clear Channel’s iHeartRadio is one of the major streaming sites for broadcast and custom digital stations. The second kind of online radio station is one that has been created exclusively for the Internet. Pandora, Grooveshark, Yahoo! Music, AOL Radio, and Last.fm are some of the leading Internet radio station services. In fact, services like Pandora allow users to have more control over their listening experience and the selections that are played. Listeners can create individualized stations based on a specific artist or song that they request. Pandora also enables users to share their musical choices on Facebook. AM/FM radio is used by nearly eight out of ten people who like to learn about new music, but YouTube, Facebook, Pandora, iTunes, iHeartRadio, Spotify, and blogs are among the competing sources for new music fans.13

Beginning in 2002, a Copyright Royalty Board established by the Library of Congress began to assess royalty fees for streaming copyrighted songs over the Internet based on a percentage of each station’s revenue. Webcasters have complained that royalty rates set by the board are too high and threaten their financial viability, particularly compared to satellite radio, which pays a lower royalty rate, and broadcasters, who pay no royalty rates at all. For decades, radio broadcasters have paid mechanical royalties to songwriters and music publishers, but no royalties to the performing artists or record companies. Broadcasters have argued that the promotional value of getting songs played is sufficient compensation.

In 2009, Congress passed the Webcaster Settlement Act, which was considered a lifeline for Internet radio. The act enabled Internet stations to negotiate royalty fees directly with the music industry, at rates presumably more reasonable than what the Copyright Royalty Board had proposed. In 2012, Clear Channel became the first company to strike a deal directly with the recording industry. Clear Channel pledged to pay royalties to Big Machine Label Group—one of the country’s largest independent labels—for broadcasting the songs of Taylor Swift and its other artists, in exchange for a limit on royalties it must pay for streaming those artists’ music on its iHeartRadio.com site. The chairman and CEO of the Recording Industry Association of America said he was pleased to hear “Clear Channel is stating that artists and record companies deserve to be paid and that promotion isn’t enough.”14

Clear Channel’s deal with the music industry opened up new dialogue about equalizing the royalty rates paid by broadcast radio, satellite radio, and Internet radio. Tim Westergren, founder of Pandora, argued before Congress in 2012 that the rates were most unfair to companies like his. In the previous year, Westergren said, Pandora paid 50 percent of its revenue to performance royalties, whereas satellite radio service SiriusXM paid 7.5 percent of its revenue to performance royalties, and broadcast radio paid nothing. He noted that a car equipped with an AM/FM radio, satellite radio, and streaming Internet radio could deliver the same song to a listener through all three technologies, but the various radio services would pay markedly different levels of performance royalties to the artist and recording company.15

Podcasting and Portable Listening

VideoCentral  Mass Communication

Mass Communication

Radio: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow Scholars and radio producers explain how radio adapts to and influences other media.

Discussion: Do you expect that the Internet will be the end of radio, or will radio stations still be around decades from now?

Developed in 2004, podcasting (the term marries iPod and broadcasting) refers to the practice of making audio files available on the Internet so listeners can download them onto their computers and transfer them to portable MP3 players or listen to the files on the computer. This popular distribution method quickly became mainstream, as mass media companies created commercial podcasts to promote and extend existing content, such as news and reality TV, while independent producers kept pace with their own podcasts on niche topics like knitting, fly fishing, and learning Russian.

Podcasts have led the way for people to listen to radio on mobile devices like the iPod and smartphones. Satellite radio, Internet-only stations like Pandora and Grooveshark, sites that stream traditional broadcast radio like iHeartRadio, and public radio like NPR all offer apps for smartphones and touchscreen devices like the iPad, which has also led to a resurgence in portable listening. Traditional broadcast radio stations are becoming increasingly mindful that they need to reach younger listeners on the Internet, and that Internet radio is no longer tethered to a computer.

For the broadcast radio industry, portability used to mean listening on a transistor or car radio. But with the digital turn to iPods and mobile phones, broadcasters haven’t been as easily available on today’s primary portable audio devices. Hoping to change that, the National Association of Broadcasters (NAB) has been lobbying the FCC and mobile phone industry to include FM radio capability in all mobile phones. According to the NAB, adding an FM radio chip in the manufacturing of mobile phones would cost less than a dollar, and add little bulk, with the chip just the size of a nail head. In a survey, about two-thirds of mobile phone users reported they would use a built-in radio.16 The NAB argues that the radio chip would be most important for enabling listeners to access broadcast radio in times of emergencies and disasters. But the chip would also be commercially beneficial for radio broadcasters, putting them on the same digital devices as their nonbroadcast radio competitors like Pandora.