Marconi and the Inventors of Wireless Telegraphy

In 1894, Guglielmo Marconi, a twenty-year-old, self-educated Italian engineer, read Hertz’s work and understood that developing a way to send high-speed messages over great distances would transform communication, the military, and commercial shipping. Although revolutionary, the telephone and the telegraph were limited by their wires, so Marconi set about trying to make wireless technology practical. First, he attached Hertz’s spark-gap transmitter to a Morse telegraph key, which could send out dot-dash signals. The electrical impulses traveled into a Morse inker, the machine that telegraph operators used to record the dots and dashes onto narrow strips of paper. Second, Marconi discovered that grounding—connecting the transmitter and receiver to the earth—greatly increased the distance over which he could send signals.

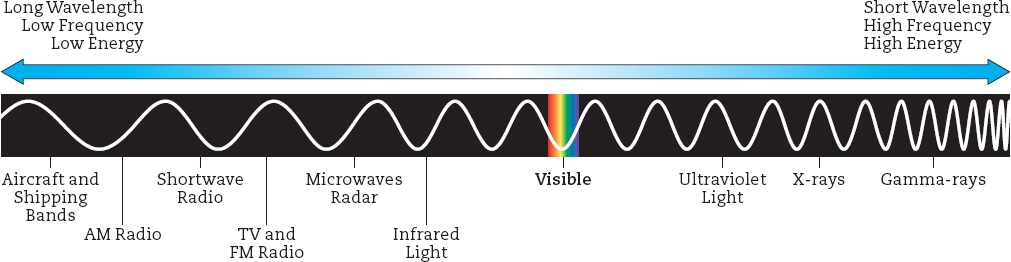

Source: NASA, http://imagine.gsfc.nasa.gov/docs/science/know_l1/emspectrum.html.

In 1896, Marconi traveled to England, where he received a patent on wireless telegraphy, a form of voiceless point-to-point communication. In London, in 1897, he formed the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company, later known as British Marconi, and began installing wireless technology on British naval and private commercial ships. In 1899, he opened a branch in the United States, establishing a company nicknamed American Marconi. That same year, he sent the first wireless Morse code signal across the English Channel to France, and in 1901 he relayed the first wireless signal across the Atlantic Ocean. Although Marconi was a successful innovator and entrepreneur, he saw wireless telegraphy only as point-to-point communication, much like the telegraph and the telephone, not as a one-to-many mass medium. He also confined his applications to Morse code messages for military and commercial ships, leaving others to explore the wireless transmission of voice and music.

History often cites Marconi as the “father of radio,” but another inventor unknown to him was making parallel discoveries about wireless telegraphy in Russia. Alexander Popov, a professor of physics in St. Petersburg, was also experimenting with sending wireless messages over distances. Popov announced to the Russian Physicist Society of St. Petersburg on May 7, 1895, that he had transmitted and received signals over a distance of six hundred yards.2 Yet Popov was an academic, not an entrepreneur, and after Marconi accomplished a similar feat that same summer, Marconi was the first to apply for and receive a patent. However, May 7 is celebrated as “Radio Day” in Russia.

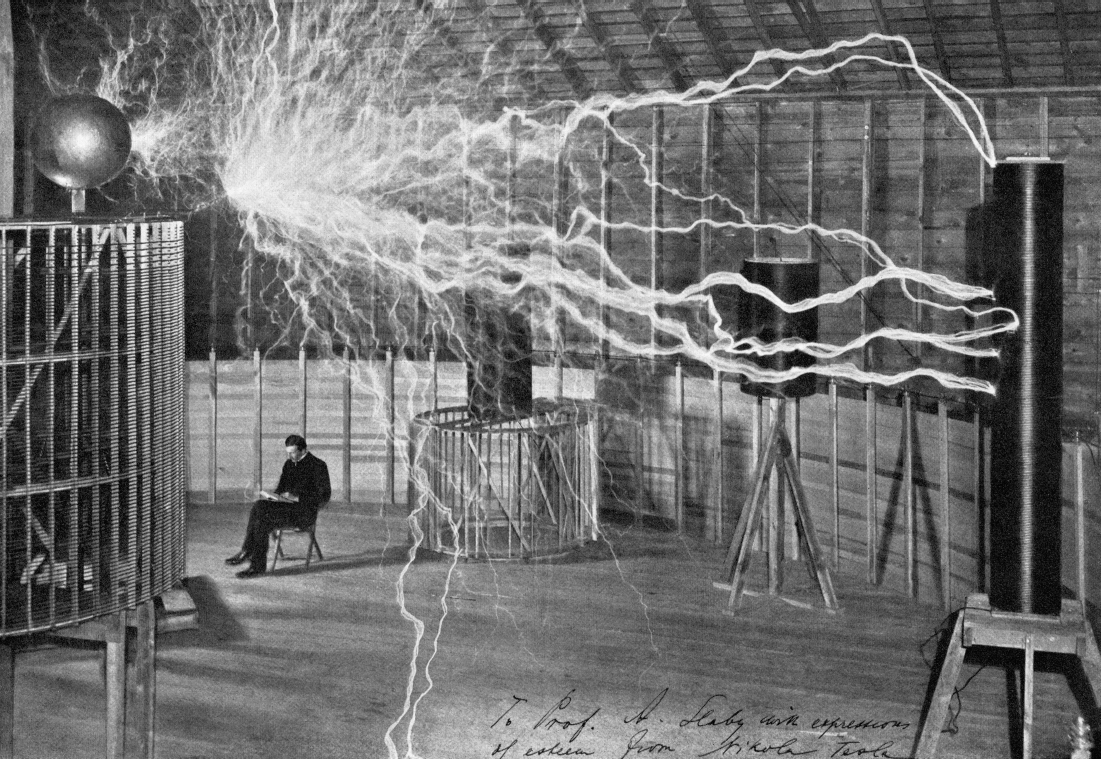

It is important to note that the work of Popov and Marconi was preceded by that of Nikola Tesla, a Serbian-Croatian inventor who immigrated to New York in 1884. Tesla, who also conceived the high-capacity alternating current systems that made worldwide electrification possible, invented a wireless system in 1892. A year later, Tesla successfully demonstrated his device in St. Louis, with his transmitter lighting up a receiver tube thirty feet away.3 However, Tesla’s work was overshadowed by Marconi’s; Marconi used much of Tesla’s work in his own developments, and for years Tesla was not associated with the invention of radio. Tesla never received great financial benefits from his breakthroughs, but in 1943 (a few months after he died penniless in New York) the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Marconi’s wireless patent and deemed Tesla the inventor of radio.4