Tracking Technology

TRACKING TECHNOLOGY

Don’t Touch That Remote: TV Pilots Turn to Net, Not Networks

by Brian Stelter

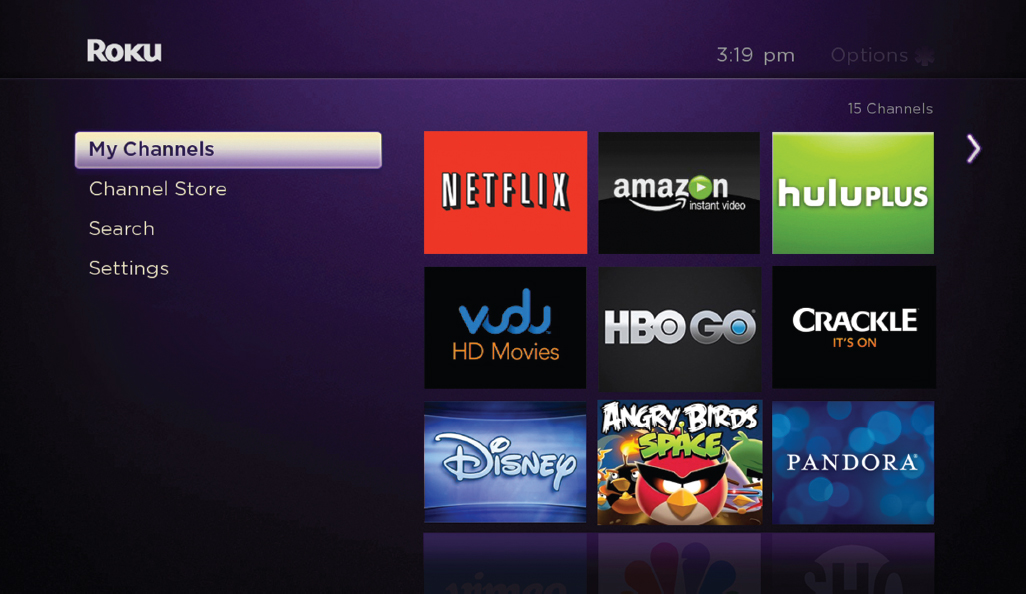

When Amazon.com sizes up the television marketplace, it sees opportunity. Internet-delivered TV, which until recently was unready for prime time, is the new front in the war for Americans’ attention spans. Netflix is following up on the $100 million drama House of Cards with four more series this year. Microsoft is producing programming for the Xbox video game console with the help of a former CBS president. Other companies, from AOL to Sony to Twitter, are likely to follow.

The companies are, in effect, creating new networks for television through broadband pipes and also giving rise to new rivalries—among one another, as between Amazon and Netflix, and with the big but vulnerable broadcast networks as well.

The competition has only just begun. Amazon is making pilot episodes for at least six comedies and five children’s shows, with more to be announced soon. Two pilots got series orders in late 2013. Netflix has been ordering entire seasons of its shows without seeing pilots first.

Microsoft has said comparatively little about its plans. But all three companies are commissioning TV shows because they have millions of subscribers on monthly or yearly subscription plans. Though the shows may be loss leaders, executives say that having exclusive content—something that cannot be seen anywhere else—increases the likelihood that existing subscribers will keep paying and that new ones will sign up.

The proliferation of shows is generally seen as a good thing for viewers, who have more choices about what to watch and when, and for producers and actors, who have more places to be seen and heard. But the trend may inflame cable companies’ concerns about cord-cutting by subscribers who decide there’s enough to watch online. At the same time, the rise of Internet-only shows may make viewers more dependent on the broadband cord. In many cases, though, both cable and broadband are supplied by the same company.

Unlike the early stabs at Internet television, these shows look and feel like traditional TV. That is partly because more viewers are watching Internet content on big-screen TV sets, but it is mostly because the companies involved are throwing money at the screens: each of the Amazon comedy pilots cost the company upward of $1 million, according to people involved in their production, which is less than the $2 million invested in a broadcast comedy pilot, but more than is typically invested in cable pilots.

Not only are the budgets comparable, so are the perks for actors and creators—like trailers and car-service pickups. The writers are guild members. The actors have what the people involved say are standard television contracts, with options for several seasons if shows succeed.

“There’s absolutely no difference” between TV and these new productions, says Jeffrey Tambor, who starred in HBO’s Larry Sanders Show, then Fox’s Arrested Development. Now he is an online pioneer: In 2013, he reprised his character for Netflix’s new season of Arrested. While taping that show, he read the script for The Onion Presents: The News, an Amazon pilot, and signed up.

Analysts say they expect more TV investment to come, including from companies that do not have monthly subscribers to please. YouTube, for instance, the biggest video Web site of all, makes its money from ads, not from subscriptions. But it has paid dozens of outside producers to start channels so that it has original, professional content. And its owner, Google, can afford to pay many more.

Similar logic is spurring cable channels, which each receive a small piece of cable subscribers’ monthly payments, to come up with more dramas and sitcoms that they can call their own. This brings up a conundrum, of course: too much great TV to watch, and not enough time.

Source: Brian Stelter, “Don’t Touch That Remote: TV Pilots Turn to Net, Not Networks,” New York Times, March 4, 2013, http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/05/business/media/online-only-tv-shows-join-fight-for-attention.html.