The Development of the Hollywood Style

“The thing of a musical is that you take a simple story, and tell it in a complicated way.”

BAZ LUHRMANN, AT THE 2002 ACADEMY AWARDS, ON MOULIN ROUGE!

By the time sound came to movies, Hollywood dictated not only the business but also the style of most moviemaking worldwide. That style, or model, for storytelling developed with the rise of the studio system in the 1920s, solidified during the first two decades of the sound era, and continues to dominate American filmmaking today. The model serves up three ingredients that give Hollywood movies their distinctive flavor: the narrative, the genre, and the author (or director). The right blend of these ingredients—combined with timing, marketing, and luck—has led to many movie hits, from 1930s and 1940s classics like It Happened One Night, Gone with the Wind, The Philadelphia Story, and Casablanca to recent successes like The Hunger Games (2012) and Lincoln (2012).

Hollywood Narratives

American filmmakers from D. W. Griffith to Steven Spielberg have understood the allure of narrative, which always includes two basic components: the story (what happens to whom) and the discourse (how the story is told). Further, Hollywood codified a familiar narrative structure across all genres. Most movies, like most TV shows and novels, feature recognizable character types (protagonist, antagonist, romantic interest, sidekick); a clear beginning, middle, and end (even with flashbacks and flash-forwards, the sequence of events is usually clear to the viewer); and a plot propelled by the main character experiencing and resolving a conflict by the end of the movie.

Within Hollywood’s classic narratives, filmgoers find an amazing array of intriguing cultural variations. For example, familiar narrative conventions of heroes, villains, conflicts, and resolutions may be made more unique with inventions like computer-generated imagery (CGI) or digital remastering for an IMAX 3-D Experience release. This combination of convention and invention—standardized Hollywood stories and differentiated special effects—provides a powerful economic package that satisfies most audiences’ appetites for both the familiar and the distinctive.

Hollywood Genres

In general, Hollywood narratives fit a genre, or category, in which conventions regarding similar characters, scenes, structures, and themes recur in combination. Grouping films by category is another way for the industry to achieve the two related economic goals of product standardization and product differentiation. By making films that fall into popular genres, the movie industry provides familiar models that can be imitated. It is much easier for a studio to promote a film that already fits into a preexisting category with which viewers are familiar. Among the most familiar genres are comedy, drama, romance, action/adventure, mystery/suspense, western, gangster, horror, fantasy/science fiction, musical, and film noir.

Variations of dramas and comedies have long dominated film’s narrative history. A western typically features “good” cowboys battling “evil” bad guys, as in True Grit (2010), or resolves tension between the natural forces of the wilderness and the civilizing influence of a town. Romances (such as The Vow, 2012) present conflicts that are mediated by the ideal of love. Another popular genre, mystery/suspense (such as Inception, 2010), usually casts “the city” as a corrupting place that needs to be overcome by the moral courage of a heroic detective.7

Because most Hollywood narratives try to create believable worlds, the artificial style of musicals is sometimes a disruption of what many viewers expect. Musicals’ popularity peaked in the 1940s and 1950s, but they showed a small resurgence in the 2000s with Moulin Rouge! (2001), Chicago (2002), and Les Misérables (2012). Still, no live-action musicals rank among the top fifty highest-grossing films of all time.

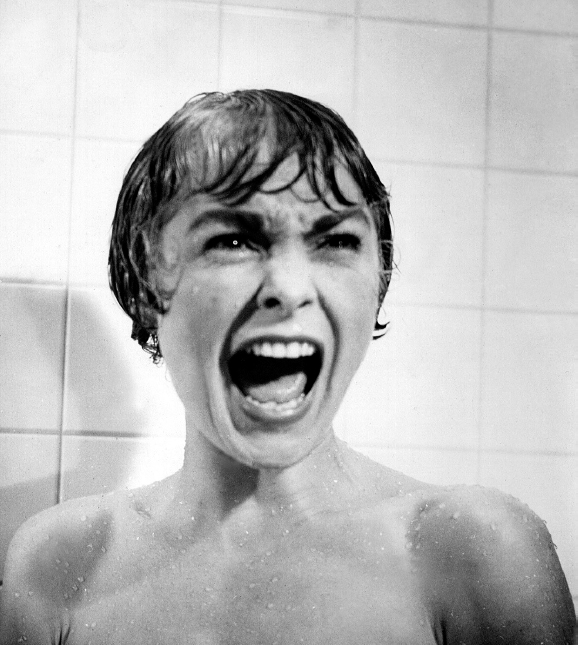

Another fascinating genre is the horror film, which also claims none of the top fifty highest-grossing films of all time. In fact, from Psycho (1960) to The Cabin in the Woods (2012), this lightly regarded genre has earned only one Oscar for best picture: Silence of the Lambs (1991). Yet these movies are extremely popular with teenagers, among the largest theatergoing audience, who are in search of cultural choices distinct from those of their parents. Critics suggest that the teen appeal of horror movies is similar to the allure of gangster rap or heavy-metal music: that is, the horror genre is a cultural form that often carries anti-adult messages or does not appeal to most adults.

The film noir genre (French for “black film”) developed in the United States in the late 1920s and hit its peak after World War II. Still, the genre continues to influence movies today. Using low-lighting techniques, few daytime scenes, and bleak urban settings, films in this genre (such as The Big Sleep, 1946, and Sunset Boulevard, 1950) explore unstable characters and the sinister side of human nature. Although the French critics who first identified noir as a genre place these films in the 1940s, their influence resonates in contemporary films—sometimes called neo-noir—including Se7en (1995), L.A. Confidential (1997), and Sin City (2005).

Hollywood “Authors”

In commercial filmmaking, the director serves as the main “author” of a film. Sometimes called “auteurs,” successful directors develop a particular cinematic style or an interest in particular topics that differentiates their narratives from those of other directors. Alfred Hitchcock, for instance, redefined the suspense drama through editing techniques that heightened tension (Rear Window, 1954; Vertigo, 1958; North by Northwest, 1959; Psycho, 1960).

The contemporary status of directors stems from two breakthrough films: Dennis Hopper’s Easy Rider (1969) and George Lucas’s American Graffiti (1973), which became surprise box-office hits. Their inexpensive budgets, rock-and-roll soundtracks, and big payoffs created opportunities for a new generation of directors. The success of these films exposed cracks in the Hollywood system, which was losing money in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Studio executives seemed at a loss to explain and predict the tastes of a new generation of moviegoers. Yet Hopper and Lucas had tapped into the anxieties of the postwar baby-boom generation in its search for self-realization, its longing for an innocent past, and its efforts to cope with the turbulence of the 1960s.

This opened the door for a new wave of directors who were trained in California or New York film schools and were also products of the 1960s, such as Francis Ford Coppola (The Godfather, 1972), William Friedkin (The Exorcist, 1973), Steven Spielberg ( Jaws, 1975), Martin Scorsese (Taxi Driver, 1976), Brian De Palma (Carrie, 1976), and George Lucas (Star Wars, 1977). Combining news or documentary techniques and Hollywood narratives, these films demonstrated how mass media borders had become blurred and how movies had become dependent on audiences who were used to television and rock and roll. These films signaled the start of a period that Scorsese has called “the deification of the director.” A handful of successful directors gained the kind of economic clout and celebrity standing that had belonged almost exclusively to top movie stars.

“Every film school in the world has equal numbers of boys and girls—but something happens.”

JANE CAMPION, FILM DIRECTOR, 2009

Although the status of directors grew in the 1960s and 1970s, recognition for women directors of Hollywood features remained rare.8 A breakthrough came with Kathryn Bigelow’s best director Academy Award for The Hurt Locker (2009), which also won the best picture award. Prior to Bigelow’s win, only three women had received an Academy Award nomination for directing a feature film: Lina Wertmuller in 1976 for Seven Beauties, Jane Campion in 1994 for The Piano, and Sofia Coppola in 2004 for Lost in Translation. Both Wertmuller and Campion are from outside the United States, where women directors frequently receive more opportunities for film development. Women in the United States often get an opportunity because of their prominent standing as popular actors; Barbra Streisand, Jodie Foster, Penny Marshall, and Sally Field all fall into this category. Other women have come to direct films via their scriptwriting achievements. For example, the late essayist Nora Ephron, who wrote Silkwood (1983) and wrote/produced When Harry Met Sally (1989), later directed a number of successful films, including Julie and Julia (2009). More recently, some women directors like Bigelow, Catherine Hardwicke (Red Riding Hood, 2011), Nancy Meyers (It’s Complicated, 2009), Lone Scherfig (One Day, 2011), Debra Granik (Winter’s Bone, 2010), and Kimberly Peirce (Carrie, 2012) have moved past debut films and proven themselves as experienced studio auteurs.

“Growing up in this country, the rich culture I saw in my neighborhood, in my family—I didn’t see that on television or on the movie screen. It was always my ambition that if I was successful I would try to portray a truthful portrait of African Americans in this country, negative and positive.”

SPIKE LEE, FILMMAKER, 1996

Minority groups, including African Americans, Asian Americans, and Native Americans, have also struggled for recognition in Hollywood. Still, some have succeeded as directors, crossing over from careers as actors or gaining notoriety through independent filmmaking. Among the most successful contemporary African American directors are Kasi Lemmons (Talk to Me, 2007), Lee Daniels (The Butler, 2013), John Singleton (Four Brothers, 2005), Tyler Perry (A Madea Christmas, 2013), and Spike Lee (Red Hook Summer, 2012). (See “Case Study: Breaking through Hollywood’s Race Barrier”.) Asian Americans M. Night Shyamalan (After Earth, 2013), Ang Lee (Life of Pi, 2012), Wayne Wang (Snow Flower and the Secret Fan, 2011), and documentarian Arthur Dong (Hollywood Chinese, 2007) have built immensely accomplished directing careers. Chris Eyre (A Year in Mooring, 2011) remains the most noted Native American director, and he works mainly as an independent filmmaker.