Case Study

CASE STUDY

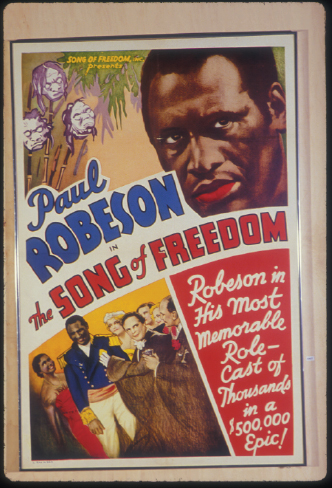

Breaking through Hollywood’s Race Barrier

Despite inequities and discrimination, a thriving black cinema existed in New York’s Harlem district during the 1930s and 1940s. Usually bankrolled by white business executives who were capitalizing on the black-only theaters fostered by segregation, independent films featuring black casts were supported by African American moviegoers, even during the Depression. But it was a popular Hollywood film, Imitation of Life (1934), that emerged as the highest-grossing film in black theaters during the mid-1930s. The film told the story of a friendship between a white woman and a black woman whose young daughter denied her heritage and passed for white, breaking her mother’s heart. Despite African Americans’ long support of the film industry, their moviegoing experience has not been the same as that of whites. From the late 1800s until the passage of Civil Rights legislation in the mid-1960s, many theater owners discriminated against black patrons. In large cities, blacks often had to attend separate theaters where new movies might not appear until a year or two after white theaters had shown them. In smaller towns and in the South, blacks were often only allowed to patronize local theaters after midnight. In addition, some theater managers required black patrons to sit in less desirable areas of the theater.1

Changes took place during and after World War II, however. When the “white flight” from central cities began during the suburbanization of the 1950s, many downtown and neighborhood theaters began catering to black customers in order to keep from going out of business. By the late 1960s and early 1970s, these theaters had become major venues for popular commercial films, even featuring a few movies about African Americans, including Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? (1967), In the Heat of the Night (1967), The Learning Tree (1969), and Sounder (1972).

Based on the popularity of these films, black photographer-turned-filmmaker Gordon Parks, who directed The Learning Tree (adapted from his own novel), went on to make commercial action/adventure films, including Shaft (1971, remade by John Singleton in 2000). Popular in urban theaters, especially among black teenagers, the movies produced by Parks and his son—Gordon Parks Jr. (Super Fly, 1972)—spawned a number of commercial imitators, labeled blaxploitation movies. These films were the subject of heated cultural debates in the 1970s; like some rap songs today, they were both praised for their realistic depictions of black urban life and criticized for glorifying violence. Nevertheless, these films reinvigorated urban movie attendance, reaching an audience that had not been well served by the film industry until the 1960s.

Opportunities for black film directors have expanded since the 1980s and 1990s, although even now there is still debate about what kinds of African American representation should be on the screen. Lee Daniels received only the second Academy Award nomination for a black director for Precious: Based on the Novel “Push” by Sapphire in 2009 (the first was John Singleton, for Boyz N the Hood in 1991). Precious, about an obese, illiterate black teenage girl subjected to severe sexual and emotional abuse, was praised by many critics but decried by others who interpreted it as more blaxploitation or “poverty porn.” Sapphire, the author of Push, the novel that inspired the film, defended the story. “With Michelle, Sasha and Malia and Obama in the White House and in the post–‘Cosby Show’ era, people can’t say these are the only images out there,” she said.2