Newspapers Target Specific Readers

Historically, small-town weeklies and daily newspapers have served predominantly white, mainstream readers. However, ever since Benjamin Franklin launched the short-lived German-language Philadelphische Zeitung in 1732, newspapers aimed at ethnic groups have played a major role in initiating immigrants into American society. During the nineteenth century, Swedish-and Norwegian-language papers informed various immigrant communities in the Midwest. The early twentieth century gave rise to papers written in German, Yiddish, Russian, and Polish, assisting the massive influx of European immigrants.

Throughout the 1990s and into the twenty-first century, several hundred foreign-language daily and nondaily presses published papers in at least forty different languages in the United States. Many are financially healthy today, supported by classified ads, local businesses, and increased ad revenue from long-distance phone companies and Internet services, which see the ethnic press as an ideal place to reach those customers most likely to need international communication services.22 While the financial crisis took its toll and some ethnic newspapers failed, overall, loyal readers allowed such papers to fare better than the mainstream press.23

Most of these weekly and monthly newspapers serve some of the same functions for their constituencies—minorities and immigrants, as well as disabled veterans, retired workers, gay and lesbian communities, and the homeless—that the “majority” papers do. These papers, however, are often published outside the social mainstream. Consequently, they provide viewpoints that are different from the mostly middle-and upper-class establishment attitudes that have shaped the media throughout much of America’s history. As noted by the Pew Research Center’s Project for Excellence in Journalism, ethnic newspapers and media “cover stories about the activities of those ethnic groups in the United States that are largely ignored by the mainstream press, they provide ethnic angles to news that actually is covered more widely, and they report on events and issues taking place back in the home countries from which those populations or their family members emigrated. These outlets have also traditionally been leaders in their communities.”24

African American Newspapers

“We wish to plead our own cause. Too long have others spoken for us.”

FREEDOM’S JOURNAL, 1827

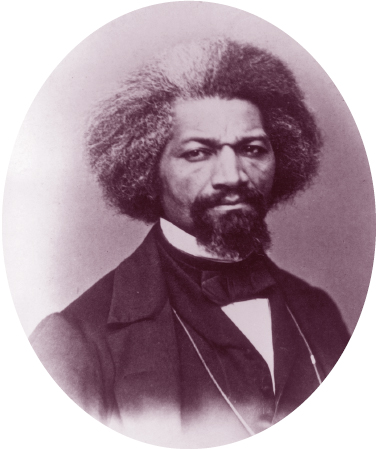

Between 1827 and the end of the Civil War in 1865, forty newspapers directed at black readers and opposed to slavery struggled for survival. These papers faced not only higher rates of illiteracy among potential readers but also hostility from white society and the majority press of the day. The first black newspaper, Freedom’s Journal, operated from 1827 to 1829 and opposed the racism of many New York newspapers. In addition, it offered a public voice for antislavery societies. Other notable papers included the Alienated American (1852–56) and the New Orleans Daily Creole, which began its short life in 1856 as the first black-owned daily in the South. The most influential oppositional newspaper was Frederick Douglass’s North Star, a weekly antislavery newspaper in Rochester, New York, which was published from 1847 to 1860 and reached a circulation of three thousand. Douglass, a former slave, wrote essays on slavery and on a variety of national and international topics.

Since 1827, 5,500 newspapers have been edited or started by African Americans.25 These papers, with an average life span of nine years, have taken stands against race baiting, lynching, and the Ku Klux Klan. They also promoted racial pride long before the Civil Rights movement. The most widely circulated black-owned paper was Robert C. Vann’s weekly Pittsburgh Courier, founded in 1910. Its circulation peaked at 350,000 in 1947—the year professional baseball was integrated by Jackie Robinson, thanks in part to relentless editorials in the Courier that denounced the color barrier in pro sports. As they have throughout their history, these papers offer oppositional viewpoints to the mainstream press and record the daily activities of black communities by listing weddings, births, deaths, graduations, meetings, and church functions. Today, the National Association of Black Journalists (NABJ) reports that there are roughly two hundred African American newspapers, including Baltimore’s Afro-American, New York’s Amsterdam News, and the Chicago Defender, which celebrated its one hundredth anniversary in 2005.26 None of these publish daily editions any longer, and most are weeklies.

The circulation rates of most black papers dropped sharply after the 1960s. The combined circulation of the local and national editions of the Pittsburgh Courier, for instance, dropped from 202,080 in 1944 to 20,000 in 1966, when it was reorganized as the New Pittsburgh Courier. Several factors contributed to these declines. First, television and black radio stations tapped into the limited pool of money that businesses allocated for advertising. Second, some advertisers, to avoid controversy, withdrew their support when the black press started giving favorable coverage to the Civil Rights movement in the 1960s. Third, the loss of industrial urban jobs in the 1970s and 1980s not only diminished readership but also hurt small neighborhood businesses, which could no longer afford to advertise in both the mainstream and the black press. Finally, after the enactment of Civil Rights and affirmative action laws, mainstream papers raided black papers, seeking to integrate their newsrooms with African American journalists. Black papers could seldom match the offers from large white-owned dailies.

While a more integrated mainstream press hurt black papers then—an ironic effect of the Civil Rights laws—today that trend is reversing a bit as some black reporters and editors return to black newsrooms.27 Overall, however, the number of African Americans in newsrooms is declining—between 2006 and 2013, African American representation fell from 5.5 to 4.7 percent. The American Society of News Editors (ASNE) reports that there are about twelve hundred fewer African American journalists now than fifteen years ago.28

Spanish-Language Newspapers

Bilingual and Spanish-language newspapers have served a variety of Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, and other Hispanic readerships since 1808, when El Misisipi was founded in New Orleans. In the 1800s alone, Texas had more than 150 Spanish-language papers.29 Los Angeles’ La Opinión, founded in 1926, is now the nation’s largest Spanish-language daily. Other prominent publications are in Miami (La Voz and Diario Las Americas), Houston (La Información), Chicago (El Mañana Daily News and La Raza), and New York (El Diario-La Prensa). In 2011, no more than eight hundred Spanish-language papers operated in the United States, most of them weekly and nondaily papers.30

Until the late 1960s, mainstream newspapers virtually ignored Hispanic issues and culture. But with the influx of Mexican, Puerto Rican, and Cuban immigrants throughout the 1980s and 1990s, many mainstream papers began to feature weekly Spanish-language supplements. The first was the Miami Herald’s “El Nuevo Herald,” introduced in 1976. Other mainstream papers also joined in, but many folded their Spanish-language supplements by the mid-1990s. In 1995, the Los Angeles Times discontinued its supplement, “Nuestro Tiempo,” and the Miami Herald trimmed budgets and staff for “El Nuevo Herald.” Spanish-language radio and television had beaten newspapers to these potential customers and advertisers. As the U.S. Hispanic population reached 17 percent in 2013, Hispanic journalists accounted for only about 4 percent of the newsroom workforce at U.S. daily newspapers.31

Asian American Newspapers

In the 1980s, hundreds of small papers emerged to serve immigrants from Pakistan, Laos, Cambodia, and China. While people of Asian descent made up only about 4.8 percent of the U.S. population in 2010, this percentage is expected to rise to 9 percent by 2050.32 Today, fifty small U.S. papers are printed in Vietnamese. Ethnic papers like these help readers both adjust to foreign surroundings and retain ties to their traditional heritage. In addition, these papers often cover major stories downplayed in the mainstream press. For example, in the aftermath of 9/11, airport security teams detained thousands of Middle Eastern–looking men. The Weekly Bangla Patrika, a Long Island, New York, paper, reported on the one hundred people the Bangladeshi community lost in the 9/11 attacks and on how it feels to be innocent yet targeted by ethnic profiling.33

A growth area in newspapers is Chinese publications. Even amid a poor economy, a new Chinese newspaper, News for Chinese, started in 2008. The Chinese-language paper began as a free monthly distributed in the San Francisco area. By early 2009, it began publishing twice a week. The World Journal, the largest U.S.-based Chinese-language paper, publishes six editions on the East Coast; on the West Coast, the paper is known as the Chinese Daily News.34 In 2013, Asian American journalists accounted for 3 percent of newsroom jobs in the United States.35

Native American Newspapers

An activist Native American press has provided oppositional voices to mainstream American media since 1828, when the Cherokee Phoenix appeared in Georgia. Another prominent early paper was the Cherokee Rose Bud, founded in 1848 by tribal women in the Oklahoma territory. The Native American Press Association has documented more than 350 different Native American papers, most of them printed in English but a few in tribal languages. Currently, two national papers are the Native American Times, which offers perspectives on “sovereign rights, civil rights, and government-to-government relationships with the federal government,” and Indian Country Today, owned by the Oneida Nation in New York. In 2013, Native American journalists accounted for 0.37 percent of newsroom jobs in the United States (down from 0.5 in 2011).

To counter the neglect of their culture’s viewpoints by the mainstream press, Native American newspapers have helped educate various tribes about their heritage and build community solidarity. These papers also have reported on both the problems and the progress among tribes that have opened casinos and gambling resorts. Overall, these smaller papers provide a forum for debates on tribal conflicts and concerns, and they often signal the mainstream press on issues—such as gambling or hunting and fishing rights—that have particular significance for the larger culture.

The Underground Press

Source: Association of Alterna-tive Newsweeklies, http://www.aan.org.

The mid to late 1960s saw an explosion of alternative newspapers. Labeled the underground press at the time, these papers questioned mainstream political policies and conventional values, often voicing radical opinions. Generally running on shoestring budgets, they were also erratic in meeting publication schedules. Springing up on college campuses and in major cities, underground papers were inspired by the writings of socialists and intellectuals from the 1930s and 1940s and by a new wave of thinkers and artists. Particularly inspirational were poets and writers (such as Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, LeRoi Jones, and Eldridge Cleaver) and “protest” musicians (including Bob Dylan, Pete Seeger, and Joan Baez). In criticizing social institutions, alternative papers questioned the official reports distributed by public relations agents, government spokespeople, and the conventional press (see “Case Study: Alternative Journalism: Dorothy Day and I. F. Stone”).

During the 1960s, underground papers played a unique role in documenting social tension by including the voices of students, women, African Americans, Native Americans, gay men and lesbians, and others whose opinions were often excluded from the mainstream press. The first and largest underground paper, the Village Voice, was founded in Greenwich Village in 1955. It is still distributed free, surviving through advertising, and reported a circulation of 148,000 in 2013, though its staff has been cut heavily in recent years. Among campus underground papers, the Berkeley Barb was the most influential, developing amid the free-speech movement in the mid-1960s. Despite their irreverent tone, many underground papers turned a spotlight on racial and gender inequities and occasionally goaded mainstream journalism to examine social issues. Like the black press, though, many early underground papers folded after the 1960s. Given their radical outlook, it was difficult for them to appeal to advertisers. In addition, as with the black press, mainstream papers raided alternatives and expanded their own coverage of culture by hiring the underground’s best writers. Still, today more than 120 papers, reaching 25 million readers, are members of the Association of Alternative Newsweeklies (see Figure 8.1).