Convergence: Newspapers Struggle in the Move to Digital

VideoCentral  Mass Communication

Mass Communication

Community Voices: Weekly Newspapers Journalists discuss the role of local newspapers in their communities.

Discussion: In a democratic society, why might having many community voices in the news media be a good thing?

Because of their local monopoly status, many newspapers were slower than other media to confront the challenges of the Internet. But faced with competition from the 24/7 news cycle on cable, newspapers responded by developing online versions of their papers. While some observers think newspapers are on the verge of extinction as the digital age eclipses the print era, the industry is no dinosaur. In fact, the history of communication demonstrates that older mass media have always adapted; so far, books, newspapers, and magazines have adjusted to the radio, television, and movie industries. And with nearly fifteen hundred North American daily papers online in 2010, newspapers are solving one of the industry’s major economic headaches: the cost of newsprint. After salaries, paper is the industry’s largest expense, typically accounting for more than 25 percent of a newspaper’s total cost.

“In 2009, the [Christian Science] Monitor [became] the first nationally circulated newspaper to replace its daily print edition with its website.”

DAVID COOK, CHRISTIAN SCIENCE MONITOR

Online newspapers are truly taking advantage of the flexibility the Internet offers. Because space is not an issue online, newspapers can post stories and readers’ letters that they weren’t able to print in the paper edition. They can also run longer stories with more in-depth coverage, as well as offer immediate updates to breaking news. Also, most stories appear online before they appear in print; they can be posted at any time and updated several times a day.

Among the valuable resources that online newspapers offer are hyperlinks to Web sites that relate to stories and that link news reports to an archive of related articles. Free of charge or for a modest fee, a reader can search the newspaper’s database from home and investigate the entire sequence and history of an ongoing story, such as a trial, over the course of several months. Taking advantage of the Internet’s multimedia capabilities, online newspapers offer readers the ability to stream audio and video files—everything from presidential news conferences to local sports highlights to original video footage from a storm disaster. Today’s online newspapers offer readers a dynamic, rather than a static, resource.

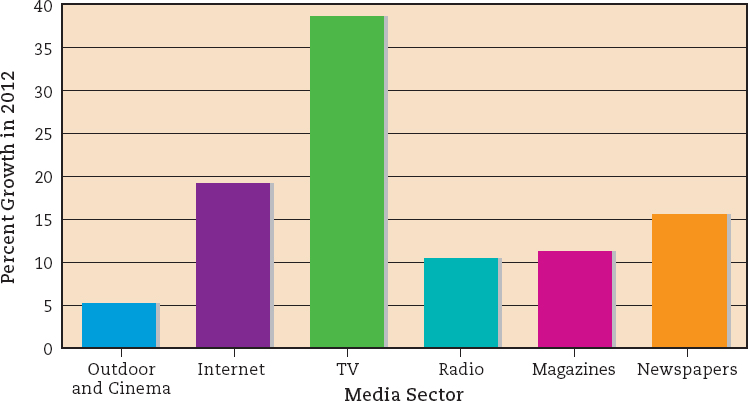

However, these advances have yet to pay off. Online ads accounted for about 13 percent of a newspaper’s advertising in 2010—up about 3 percent from 2009. So newspapers, even in decline, are still heavily dependent on print ads. But this trend does not seem likely to sustain papers for long. Ad revenue for newspaper print ads in 2009 declined 25 to 35 percent at many newspapers.50 To jump-start online revenue streams, more than four hundred daily newspapers collaborated with Yahoo! (the number one portal to newspapers online) in 2006 to begin an advertising venture that aimed to increase papers’ online revenue by 10 to 20 percent. By summer 2010, with the addition of the large Gannett chain, Yahoo! had nearly nine hundred papers in the ad partnership. During an eighteen-month period in 2009–10, the Yahoo! consortium sold over thirty thousand online ad campaigns in local markets, with most revenue shared 50/50 between Yahoo! and its partner papers.51 Still, in 2012 newspapers posted the largest decline in ad sales. (See Figure 8.2 above.)

Source: Ad Age DataCenter Analysis of Data from ZenithOptimedia, December 2012.

One of the business mistakes that most newspaper executives made near the beginning of the Internet age was giving away online content for free. Whereas their print versions always had two revenue streams—ads and subscriptions—newspaper executives weren’t convinced that online revenue would amount to much, so they used their online version as an advertisement for the printed paper. Since those early years, most newspapers are now trying to establish a paywall—charging a fee for online access to news content—but customers used to getting online content for free have shunned most online subscriptions. One paper that did charge early for online content was the Wall Street Journal, which pioneered one of the few successful paywalls in the digital era. In fact, the Journal, helped by the public’s interest in the economic crisis and 400,000 paid subscriptions to its online service, replaced USA Today as the nation’s most widely circulated newspaper in 2009. In early 2011, a University of Missouri study found 46 percent of papers with circulations under 25,000 said they charged for some online content, while only 24 percent of papers with more than 25,000 in circulation charged for content.52

An interesting case in the paywall experiments is the New York Times. In 2005, the paper began charging online readers for access to its editorials and columns, but the rest of the site was free. This system lasted only until 2007. But starting in March 2011, the paper added a paywall—a metered system that was mostly aimed at getting the New York Times’ most loyal online readers, rather than the casual online reader, to pay for online access. Under this paywall system, print subscribers would continue to get Web access free. Online-only subscribers could opt for one of three plans: $15 per month for Web and smartphone access, $20 per month for Web and tablet access, or $35 per month for an “all-you-can-eat” plan that would allow access to all the Times platforms. In its first few weeks of operation, the paper gained more than 100,000 new subscribers and lost only about 15 percent of traffic from the days of free Web access—a more positive scenario than the 50 percent loss in online traffic some observers had predicted. And by early 2013 the Times reported 668,000 paid subscribers to all its various digital options.53

By 2012, more than 150 newspapers had launched various paywalls, many of them based on the New York Times metered models, trying to reverse years of giving away their print content online for free. One smaller daily, the Augusta Chronicle in Georgia, is being studied closely by other newspapers. According the Pew State of the News Media 2012 report:

Morris Communications’ Augusta Chronicle began a metered-model pay wall four months before the Times in December 2010. Page views actually went up 5% in the next three months. The Augusta offer began by allowing up to 100 page views per month free, gradually reducing that threshold to 15. It charges digital-only subscribers $6.95 per month and print subscribers an additional $2.95 for digital access.

Larger metro dailies, including the Boston Globe, Dallas Morning News, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, and Los Angeles Times have also started their own paywalls and metered models. Pew’s annual report on the news media explains “why now,” especially since many newspaper executives for years believed that free digital news would attract readers to their print editions or that charging readers for online content would irritate them and drive them away.

The pay systems re-establish the principle that users should pay for valued content, expensive to produce, whatever the platform. It gives flexibility to raise the subscription price in later years or charge more for a particularly convenient medium like tablets. The change is unlikely to have a big financial impact, positive or negative, right away, but it better positions newspaper organizations eventually to wean themselves away from print.54

Still, only time will tell if the new paywalls will bring in badly needed revenue from newspaper readers … or drive them to find “free” news elsewhere.