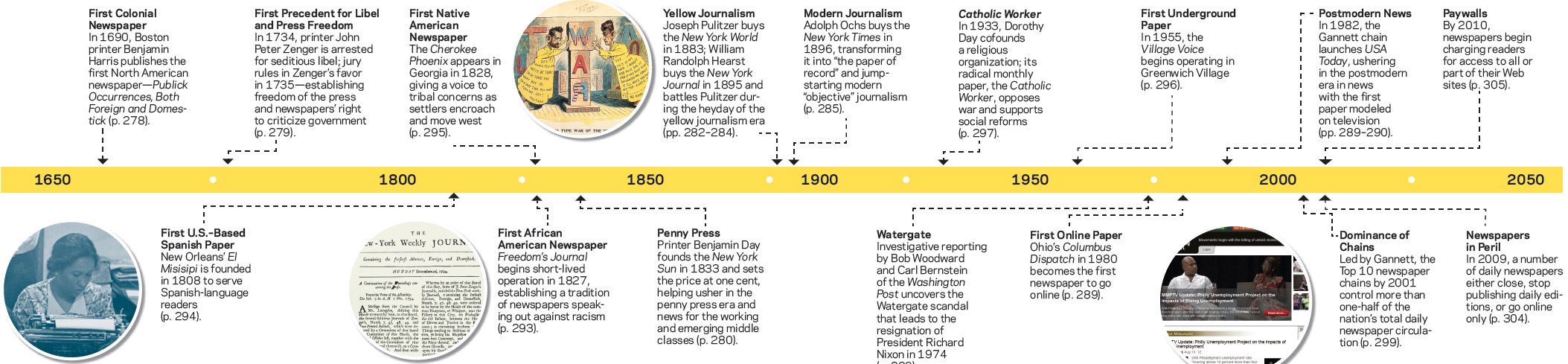

Colonial Newspapers and the Partisan Press

The novelty and entrepreneurial stages of print media development first happened in Europe with the rise of the printing press. In North America, the first newspaper, Publick Occurrences, Both Foreign and Domestick, was published on September 25, 1690, by Boston printer Benjamin Harris. The colonial government objected to Harris’s negative tone regarding British rule, and local ministers were offended by his published report that the king of France had an affair with his son’s wife. The newspaper was banned after one issue.

Newspapers: The Rise and Decline of Modern Journalism

In 1704, the first regularly published newspaper appeared in the American colonies—the Boston News-Letter, published by John Campbell. Because European news took weeks to travel by ship, these early colonial papers were not very timely. In their more spirited sections, however, the papers did report local illnesses, public floggings, and even suicides. In 1721, also in Boston, James Franklin, the older brother of Benjamin Franklin, started the New England Courant. The Courant established a tradition of running stories that interested ordinary readers rather than printing articles that appealed primarily to business and colonial leaders. In 1729, Benjamin Franklin, at age twenty-four, took over the Pennsylvania Gazette and created, according to historians, the best of the colonial papers. Although a number of colonial papers operated solely on subsidies from political parties, the Gazette also made money by advertising products.

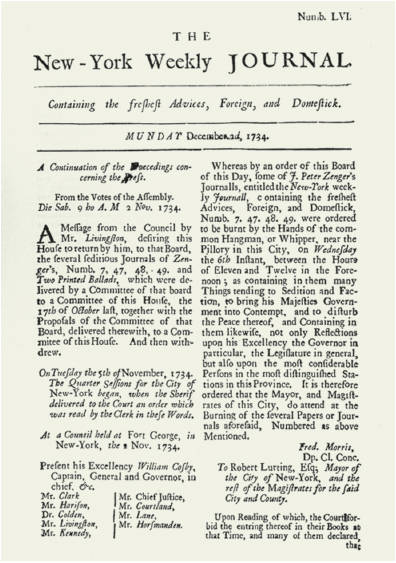

Another important colonial paper, the New-York Weekly Journal, appeared in 1733. John Peter Zenger had been installed as the printer of the Journal by the Popular Party, a political group that opposed British rule and ran articles that criticized the royal governor of New York. After a Popular Party judge was dismissed from office, the Journal escalated its attack on the governor. When Zenger shielded the writers of the critical articles, he was arrested in 1734 for seditious libel—defaming a public official’s character in print. Championed by famed Philadelphia lawyer Andrew Hamilton, Zenger ultimately won his case in 1735. A sympathetic jury, in revolt against the colonial government, decided that newspapers had the right to criticize government leaders as long as the reports were true. After the Zenger case, the British never prosecuted another colonial printer. The Zenger decision would later provide a key foundation—the right of a democratic press to criticize public officials—for the First Amendment to the Constitution, adopted as part of the Bill of Rights in 1791. (See Chapter 16 for more on the First Amendment.)

By 1765, about thirty newspapers operated in the American colonies, with the first daily paper beginning in 1784. Newspapers were of two general types: political or commercial. Their development was shaped in large part by social, cultural, and political responses to British rule and by its eventual overthrow. The gradual rise of political parties and the spread of commerce also influenced the development of early papers. Although the political and commercial papers carried both party news and business news, they had different agendas. Political papers, known as the partisan press, generally pushed the plan of the particular political group that subsidized the paper. The commercial press, by contrast, served business leaders, who were interested in economic issues. Both types of journalism left a legacy. The partisan press gave us the editorial pages, while the early commercial press was the forerunner of the business section.

From the early 1700s to the early 1800s, even the largest of these papers rarely reached a circulation of fifteen hundred. Readership was primarily confined to educated or wealthy men who controlled local politics and commerce. During this time, though, a few pioneering women operated newspapers, including Elizabeth Timothy, the first American woman newspaper publisher (and mother of eight children). After her husband died of smallpox in 1738, Timothy took over the South Carolina Gazette, established in 1734 by Benjamin Franklin and the Timothy family. Also during this period, Anna Maul Zenger ran the New-York Weekly Journal throughout her husband’s trial and after his death in 1746.7