The Age of Yellow Journalism: Sensationalism and Investigation

The rise of competitive dailies and the penny press triggered the next significant period in American journalism. In the late 1800s, yellow journalism emphasized profitable papers that carried exciting human-interest stories, crime news, large headlines, and more readable copy. Generally regarded as sensationalistic and the direct forerunner of today’s tabloid papers, reality TV, and celebrity-centered shows like Access Hollywood, yellow journalism featured two

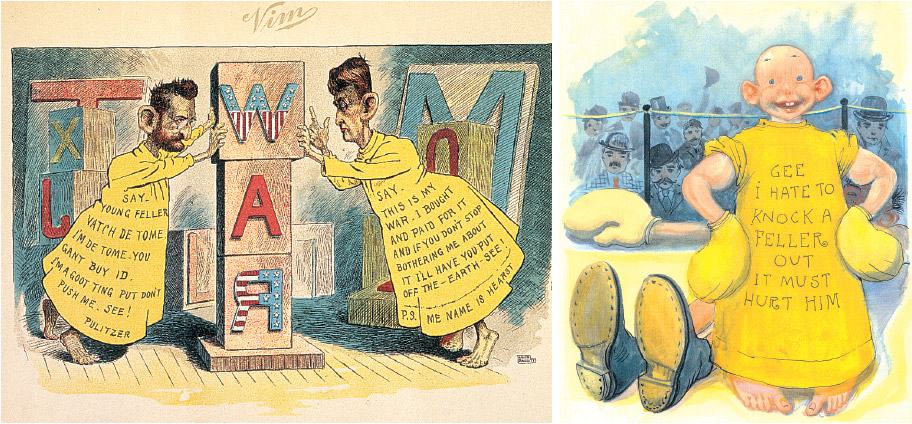

During this period, a newspaper circulation war pitted Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World against William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal. A key player in the war was the first popular cartoon strip, The Yellow Kid, created in 1895 by artist R. F. Outcault, who once worked for Thomas Edison. The phrase yellow journalism has since become associated with the cartoon strip, which was shuttled back and forth between the Hearst and Pulitzer papers during their furious battle for readers in the mid-to late 1890s.

Pulitzer and the New York World

“There is room in this great and growing city for a journal that is not only cheap but bright, not only bright but large … that will expose all fraud and sham, fight all public evils and abuses—that will serve and battle for the people.”

JOSEPH PULITZER, PUBLISHER, NEW YORK WORLD, 1883

Joseph Pulitzer, a Jewish-Hungarian immigrant, began his career in newspaper publishing in the early 1870s as part owner of the St. Louis Post. He then bought the bankrupt St. Louis Dispatch for $2,500 at an auction in 1878 and merged it with the Post. The Post-Dispatch became known for stories that highlighted “sex and sin” (“A Denver Maiden Taken from Disreputable House”) and satires of the upper class (“St. Louis Swells”). Pulitzer also viewed the Post-Dispatch as a “national conscience” that promoted the public good. He carried on the legacies of James Gordon Bennett: making money and developing a “free and impartial” paper that would “serve no party but the people.” Within five years, the Post-Dispatch became one of the most influential newspapers in the Midwest.

In 1883, Pulitzer bought the New York World for $346,000. He encouraged plain writing and the inclusion of maps and illustrations to help immigrant and working-class readers understand the written text. In addition to running sensational stories on crime and sex, Pulitzer instituted advice columns and women’s pages. Like Bennett, Pulitzer treated advertising as a kind of news that displayed consumer products for readers. In fact, department stores became major advertisers during this period. This development contributed directly to the expansion of consumer culture and indirectly to the acknowledgment of women as newspaper readers. Eventually (because of pioneers like Nellie Bly—see Chapter 14), newspapers began employing women as reporters.

The World reflected the contradictory spirit of the yellow press. It crusaded for improved urban housing, better conditions for women, and equitable labor laws. It campaigned against monopoly practices by AT&T, Standard Oil, and Equitable Insurance. Such popular crusades helped lay the groundwork for tightening federal antitrust laws in the early 1910s. At the same time, Pulitzer’s paper manufactured news events and staged stunts, such as sending star reporter Nellie Bly around the world in seventy-two days to beat the fictional “record” in the popular 1873 Jules Verne novel Around the World in Eighty Days. By 1887, the World’s Sunday circulation had soared to more than 250,000, the largest anywhere.

Pulitzer created a lasting legacy by leaving $2 million to start the graduate school of journalism at Columbia University in 1912. In 1917, part of Pulitzer’s Columbia endowment established the Pulitzer Prizes, the prestigious awards given each year for achievements in journalism, literature, drama, and music.

Hearst and the New York Journal

The World faced its fiercest competition when William Randolph Hearst bought the New York Journal (a penny paper founded by Pulitzer’s brother Albert). Before moving to New York, the twenty-four-year-old Hearst took control of the San Francisco Examiner when his father, George Hearst, was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1887 (the younger Hearst had recently been expelled from Harvard for playing a practical joke on his professors). In 1895, with an inheritance from his father, Hearst bought the ailing Journal and then raided Joseph Pulitzer’s paper for editors, writers, and cartoonists.

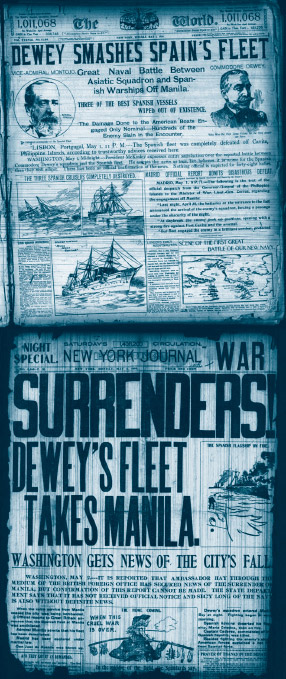

Taking his cue from Bennett and Pulitzer, Hearst focused on lurid, sensational stories and appealed to immigrant readers by using large headlines and bold layout designs. To boost circulation, the Journal invented interviews, faked pictures, and encouraged conflicts that might result in a story. One tabloid account describes “tales about two-headed virgins” and “prehistoric creatures roaming the plains of Wyoming.”8 In promoting journalism as mere dramatic storytelling, Hearst reportedly said, “The modern editor of the popular journal does not care for facts. The editor wants novelty. The editor has no objection to facts if they are also novel. But he would prefer a novelty that is not a fact to a fact that is not a novelty.”9

Hearst is remembered as an unscrupulous publisher who once hired gangsters to distribute his newspapers. He was also, however, considered a champion of the underdog, and his paper’s readership soared among the working and middle classes. In 1896, the Journal’s daily circulation reached 450,000, and by 1897 the Sunday edition of the paper rivaled the 600,000 circulation of the World. By the 1930s, Hearst’s holdings included more than forty daily and Sunday papers, thirteen magazines (including Good Housekeeping and Cosmopolitan), eight radio stations, and two film companies. In addition, he controlled King Features Syndicate, which sold and distributed articles, comics, and features to many of the nation’s dailies. Hearst, the model for Charles Foster Kane, the ruthless publisher in Orson Welles’s classic 1940 film Citizen Kane, operated the largest media business in the world—the News Corp. of its day.