Literary Forms of Journalism

By the late 1960s, many people were criticizing America’s major social institutions. Political assassinations, Civil Rights protests, the Vietnam War, the drug culture, and the women’s movement were not easily explained. Faced with so much change and turmoil, many individuals began to lose faith in the ability of institutions to oversee and ensure the social order. Members of protest movements as well as many middle-and working-class Americans began to suspect the privileges and power of traditional authority. As a result, key institutions—including journalism—lost some of their credibility.

Journalism as an Art Form

“Critics [in the 1960s] claimed that urban planning created slums, that school made people stupid, that medicine caused disease, that psychiatry invented mental illness, and that the courts promoted injustice. … And objectivity in journalism, regarded as an antidote to bias, came to be looked upon as the most insidious bias of all. For ‘objective’ reporting reproduced a vision of social reality which refused to examine the basic structures of power and privilege.”

MICHAEL SCHUDSON, DISCOVERING THE NEWS, 1978

Throughout the first part of the twentieth century—journalism’s modern era—journalistic storytelling was downplayed in favor of the inverted-pyramid style and the separation of fact from opinion. Dissatisfied with these limitations, some reporters began exploring a new model of reporting. Literary journalism, sometimes dubbed “new journalism,” adapted fictional techniques, such as descriptive details and settings and extensive character dialogue, to nonfiction material and in-depth reporting. In the United States, literary journalism’s roots are evident in the work of nineteenth-century novelists like Mark Twain, Stephen Crane, and Theodore Dreiser, all of whom started out as reporters. In the late 1930s and 1940s, literary journalism surfaced: Journalists, such as James Agee and John Hersey, began to demonstrate how writing about real events could achieve an artistry often associated only with fiction.

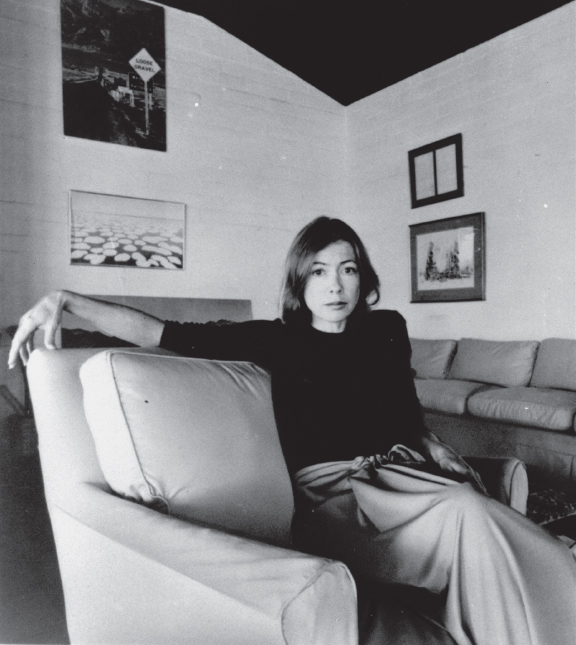

In the 1960s, Tom Wolfe, a leading practitioner of new journalism, argued for mixing the content of reporting with the form of fiction to create “both the kind of objective reality of journalism” and “the subjective reality” of the novel.17 Writers such as Wolfe (The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test), Truman Capote (In Cold Blood), Joan Didion (The White Album), Norman Mailer (Armies of the Night), and Hunter S. Thompson (Hell’s Angels) turned to new journalism to overcome flaws they perceived in routine reporting. Their often self-conscious treatment of social problems gave their writing a perspective that conventional journalism did not offer. After the 1960s’ tide of intense social upheaval ebbed, new journalism subsided as well. However, literary journalism not only influenced magazines like Mother Jones and Rolling Stone, but it also affected daily newspapers by emphasizing longer feature stories on cultural trends and social issues with detailed description or dialogue. Today, writers such as Adrian Nicole LeBlanc (Random Family), Dexter Filkins (The Forever War), and Asne Seierstad (The Bookseller of Kabul) keep this tradition alive.

The Attack on Journalistic Objectivity

Former New York Times columnist Tom Wicker argued that in the early 1960s an objective approach to news remained the dominant model. According to Wicker, the “press had so wrapped itself in the paper chains of ‘objective journalism’ that it had little ability to report anything beyond the bare and undeniable facts.”18 Through the 1960s, attacks on the detachment of reporters escalated. News critic Jack Newfield rejected the possibility of genuine journalistic impartiality and argued that many reporters had become too trusting and uncritical of the powerful: “Objectivity is believing people with power and printing their press releases.”19 Eventually, the ideal of objectivity became suspect along with the authority of experts and professionals in various fields.

TABLE 8.2

EXCEPTIONAL WORKS OF AMERICAN JOURNALISM

| Journalists | Title or Subject | Publisher | Year | |

| 1 | John Hersey | “Hiroshima” | New Yorker | 1946 |

| 2 | Rachel Carson | Silent Spring | Houghton Mifflin | 1962 |

| 3 | Bob Woodward/Carl Bernstein | Watergate investigation | Washington Post | 1972–73 |

| 4 | Edward R. Murrow | Battle of Britain | CBS Radio | 1940 |

| 5 | Ida Tarbell | “The History of the Standard Oil Company” | McClure’s Magazine | 1902–04 |

| 6 | Lincoln Steffens | “The Shame of the Cities” | McClure’s Magazine | 1902–04 |

| 7 | John Reed | Ten Days That Shook the World | Random House | 1919 |

| 8 | H. L. Mencken | Coverage of the Scopes “monkey” trial | Baltimore Sun | 1925 |

| 9 | Ernie Pyle | Reports from Europe and the Pacific during World War II | Scripps-Howard newspapers | 1940–45 |

| 10 | Edward R. Murrow/ Fred Friendly | Investigation of Senator Joseph McCarthy | CBS Television | 1954 |

Working under the aegis of New York University’s journalism department, thirty-six judges compiled a list of the Top 100 works of American journalism in the twentieth century. The list takes into account not just the newsworthiness of the event but the craft of the writing and reporting. What do you think of the Top 10 works listed here? What are some problems associated with a list like this? Do you think newswriting should be judged in the same way we judge novels or movies?

Source: New York University, Department of Journalism, New York, N.Y., 1999.

A number of reporters responded to the criticism by rethinking the framework of conventional journalism and adopting a variety of alternative techniques. One of these was advocacy journalism, in which the reporter actively promotes a particular cause or viewpoint. Precision journalism, another technique, attempts to make the news more scientifically accurate by using poll surveys and questionnaires. Throughout the 1990s, precision journalism became increasingly important. However, critics have charged that in every modern presidential campaign—including that of 2012—too many newspapers and TV stations became overly reliant on political polls, thus reducing campaign coverage to “racehorse” journalism, telling only “who’s ahead” and “who’s behind” stories rather than promoting substantial debates on serious issues. (See Table 8.2 for top works in American journalism.)