Introduction

| 9 |

| Magazines in the Age of Specialization |

Cosmopolitan didn’t always have cover photos of women with plunging necklines, or cover lines like “67 New Sex Tricks” and “The Sexiest Things to Do after Sex.” As the magazine itself says, “The story of how a ’60s babe named Helen Gurley Brown (you’ve probably heard of her) transformed an antiquated general-interest mag called Cosmopolitan into the must-read for young, sexy single chicks is pretty damn amazing.”1

In fact, Cosmopolitan had at least four format changes before Helen Gurley Brown came along. The magazine was launched in 1886 as an illustrated monthly for the modern family (meaning it was targeted at married women) with articles on cooking, child care, household decoration, and occasionally fashion, featuring illustrated images of women in the hats and high collars of late-Victorian fashion.2

But the magazine was thin on content and almost folded. Cosmopolitan was saved in 1889, when journalist and entrepreneur John Brisben Walker gave it a second chance as an illustrated magazine of literature and insightful reporting.

The magazine featured writers like Edith Wharton, Rudyard Kipling, and Theodore Dreiser and serialized entire books, including H. G. Wells’s The War of the Worlds. Walker, seeing the success of contemporary newspapers in New York, was not above stunt reporting either. When Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World sent off reporter Nellie Bly to travel the world in less than eighty days in 1889 (challenging the premise of Jules Verne’s 1873 novel, Around the World in Eighty Days), Walker sent reporter Elizabeth Bisland around the world in the opposite direction for a more literary travel account.3 Walker’s leadership turned Cosmopolitan into a respected magazine with increased circulation and a strong advertising base.

Walker sold Cosmopolitan at a profit to William Randolph Hearst (Pulitzer’s main competitor) in 1905. Under Hearst, Cosmopolitan had its third rebirth—this time as a muckraking magazine. As magazine historians explain, Hearst was a U.S. representative who “had his eye on the presidency and planned to use his newspapers and the recently bought Cosmopolitan to stir up further discontent over the trusts and big business.”4 Cosmopolitan’s first big muckraking series, David Graham Phillips’s “The Treason of the Senate” in 1906, didn’t help Hearst’s political career, but it did boost the circulation of the magazine by 50 percent, and was reprinted in Hearst newspapers for even more exposure.

But by 1912, the progressive political movement that had given impetus to muckraking journalism was waning. Cosmopolitan, in its fourth incarnation, became like a version of its former self, an illustrated literary monthly targeted to women, with short stories and serialized novels by popular writers like Damon Runyon, Sinclair Lewis, and Faith Baldwin.

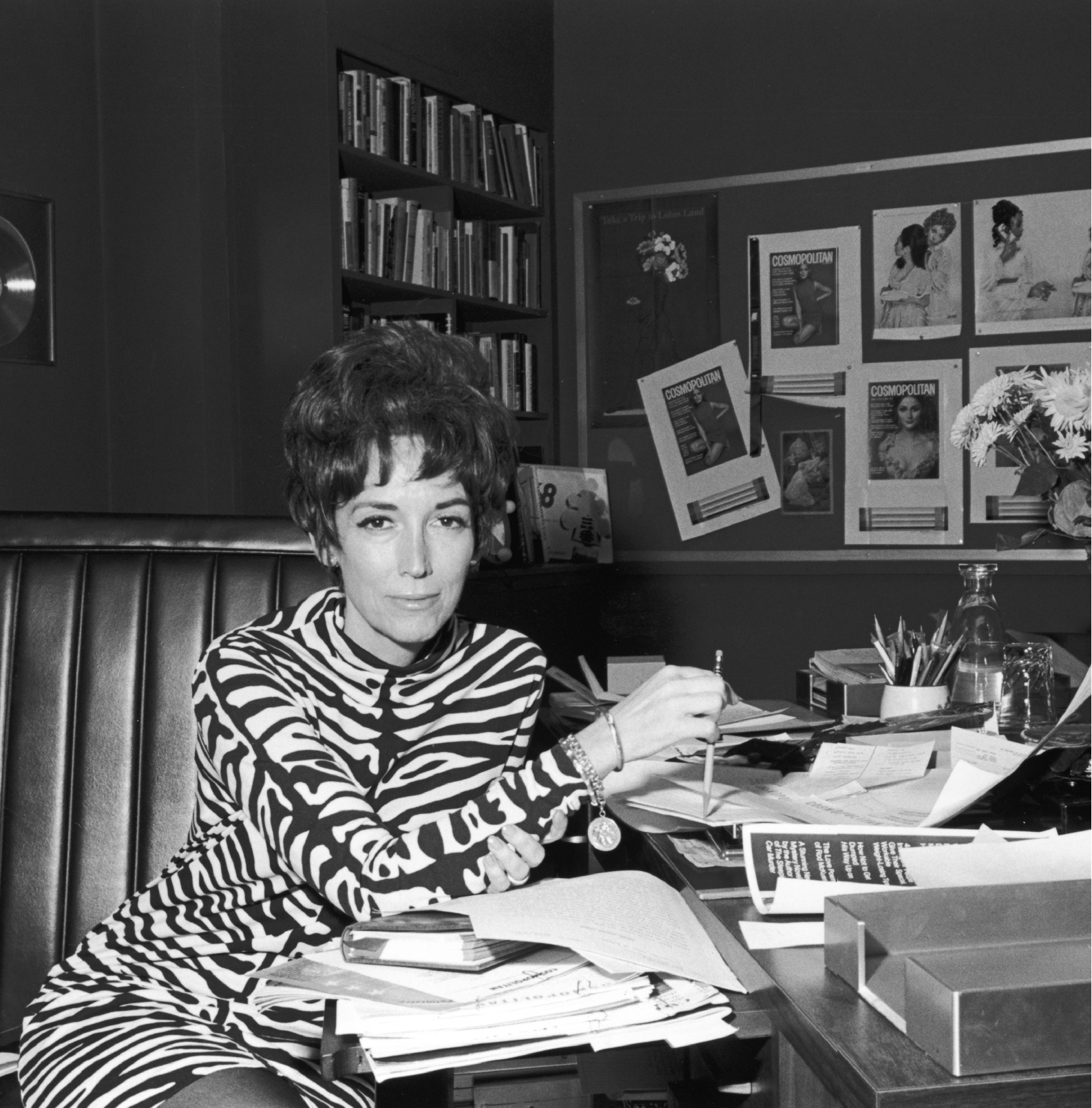

Cosmopolitan had great success as an upscale literary magazine, but by the early 1960s the format had become outdated and readership and advertising had declined. At this point, the magazine had its most radical makeover. In 1962, Helen Gurley Brown, one of the country’s top advertising copywriters, was recently married (at age forty) and wrote the best-selling book Sex and the Single Girl. When she proposed a magazine modeled on the book’s vision of strong, sexually liberated women, the Hearst Corporation hired her in 1965 as editor in chief to reinvent Cosmopolitan. The new Cosmopolitan helped spark a sexual revolution and was marketed to the “Cosmo Girl”: women age eighteen to thirty-four with an interest in love, sex, fashion, and their careers.

Brown maintained a pink corner office in the Hearst Tower in New York until her death in 2012, but her vision of Cosmo continues today. It’s the top women’s fashion magazine—surpassing competitors like Glamour, Marie Claire, and Vogue–and has wide global influence with 64 international editions. Although its present format is far from its origins, Cosmopolitan endures based on its successful reinventions for over 127 years.

SINCE THE 1740S, magazines have played a key role in our social and cultural lives, becoming America’s earliest national mass medium. They created some of the first spaces for discussing the broad issues of the age, including public education, the abolition of slavery, women’s suffrage, literacy, and the Civil War.

SINCE THE 1740S, magazines have played a key role in our social and cultural lives, becoming America’s earliest national mass medium. They created some of the first spaces for discussing the broad issues of the age, including public education, the abolition of slavery, women’s suffrage, literacy, and the Civil War.

“For generations, Time and Newsweek fought to define the national news agenda. … That era seems to be ending. … The circulations of Time and Newsweek now stand about where they were in 1966.”

NEW YORK TIMES, 2010

In the nineteenth century, magazines became an educational forum for women, who were barred from higher education and from the nation’s political life. At the turn of the twentieth century, magazines’ probing reports would influence investigative journalism, while their use of engraving and photography provided a hint of the visual culture to come. Economically, magazines brought advertised products into households, hastening the rise of a consumer society.

Today, more than twenty thousand commercial, alternative, and noncommercial magazines are published in the United States annually. Like newspapers, radio, movies, and television, magazines reflect and construct portraits of American life. They are catalogues for daily events and experiences, but they also show us the latest products, fostering our consumer culture. We read magazines to learn something about our community, our nation, our world, and ourselves.

In this chapter, we will:

- Investigate the history of the magazine industry, highlighting the colonial and early American eras, the arrival of national magazines, and the development of photojournalism

- Focus on the age of muckraking and the rise of general-interest and consumer magazines in the modern American era

- Look at the decline of mass market magazines, TV’s impact, and how magazines have specialized in order to survive in a fragmented and converged market

- Investigate the organization and economics of magazines and their function in a democracy

As you think about the evolution of magazine culture, consider your own experiences. When did you first start reading magazines, and what magazines were they? What sort of magazines do you read today—popular mainstream magazines like Cosmo or Sports Illustrated, or niche publications that target very specific subcultures? How do you think printed magazines can best adapt to the age of the Internet? For more questions to help you think through the role of magazines in our lives, see “Questioning the Media” in the Chapter Review.

Past-Present-Future: Magazines

Long before the arrival of motion pictures or cable television, magazines were the first medium to bring visuals to the masses, and the first to segment the masses into groups of various interests or demographics. Early magazines used engravings and illustrations to visualize life; later, magazines of the twentieth century used photographs to disseminate some of the most iconic images of modern times. Although some of the largest magazines once targeted a general-interest audience, most magazines succeeded by creating content for a specific audience—e.g., Latina, for Hispanic women, or Golf Digest, for fans of the sport.

Today, the magazine industry is in the midst of a digital transition that is eviscerating its print business. Newsstand sales continue to fall, as readers sometimes find print magazine content less timely. Industry consultant John Harrington noted that timeliness poses a particular problem in celebrity magazines, where celebrity gossip can be found online. “By the time the magazine comes out, it’s old news,” he said.1

Yet, for all of the laments of the magazine industry in the present, magazines might be particularly well suited to adapt their content to the digital turn in a creative and compelling way. The relatively bite-sized content of magazines—articles, essays, photos, glorified ads—is compatible with online reading habits, and the visual nature of magazines translates well to tablet and online environments. And while most magazines have always focused on driving sales for their advertisers, tablet editions go one step better, and offer immediate links to e-commerce. One success story is the Atlantic (founded in 1857), which still distributes a print edition, but also has a network of Web sites with multimedia and timely blog posts. The Atlantic offers hope to others: in 2011, it became the first major magazine in which digital advertising revenue exceeded print ad revenue.2