The Fall of General-Interest Magazines

The decline of the weekly general-interest magazines, which had dominated the industry for thirty years, began in the 1950s. By 1957, both Collier’s (founded in 1888) and Woman’s Home Companion (founded in 1873) had folded. Each magazine had a national circulation of more than four million the year it died. No magazine with this kind of circulation had ever shut down before. Together, the two publications brought in advertising revenues of more than $26 million in 1956. Although some critics blamed poor management, both magazines were victims of changing consumer tastes, rising postal costs, falling ad revenues, and, perhaps most important, television, which began usurping the role of magazines as the preferred family medium.

TV Guide Is Born

“Starting a magazine is an intensely complicated business, with many factors in play. You have to have the right person at the right time with the right ideas.”

TINA BROWN, FORMER EDITOR OF THE DEFUNCT TALK MAGAZINE, 2002

While other magazines were just beginning to make sense of the impact of television on their readers, TV Guide appeared in 1953. Taking its cue from the pocket-size format of Reader’s Digest and the supermarket sales strategy used by women’s magazines, TV Guide, started by Walter Annenberg’s Triangle Publications, soon rivaled the success of Reader’s Digest by addressing the nation’s growing fascination with television by publishing TV listings. The first issue sold a record 1.5 million copies in ten urban markets. Because many newspapers were not yet listing TV programs, by 1962 the magazine became the first weekly to reach a circulation of 8 million with its seventy regional editions tailoring its listings to TV channels in specific areas of the country. (See Table 9.1 for the circulation figures of the Top 10 U.S. magazines.)

TV Guide’s story illustrates a number of key trends that impacted magazines beginning in the 1950s. First, TV Guide highlighted America’s new interest in specialized magazines. Second, it demonstrated the growing sales power of the nation’s checkout lines, which also sustained the high circulation rates of women’s magazines and supermarket tabloids. Third, TV Guide underscored the fact that magazines were facing the same challenge as other mass media in the 1950s: the growing power of television. TV Guide would rank among the nation’s most popular magazines in the twentieth century.

In 1988, media baron Rupert Murdoch acquired Triangle Publications for $3 billion. Murdoch’s News Corp. owned the new Fox network, and buying the then-influential TV Guide ensured that the fledgling network would have its programs listed. By the mid-1990s, Fox was using TV Guide to promote the network’s programming in the magazine’s hundred-plus regional editions. In 2005, after years of declining circulation (TV schedules in local newspapers undermined its regional editions), TV Guide became a full-size entertainment magazine, dropping its smaller digest format and its 140 regional editions. In 2008, TV Guide, once the most widely distributed magazine, was sold to a private venture capital firm for $1—less than the cost of a single issue. The TV Guide Network and TVGuide.com—both deemed more valuable assets—were sold to the film company Lionsgate Entertainment for $255 million in 2009. As TV Guide fell out of favor, Game Informer—a magazine about digital games—became a top title as it chronicled the rise of another mass media industry.

TABLE 9.1

THE TOP 10 MAGAZINES (RANKED BY PAID U.S. CIRCULATION AND SINGLE-COPY SALES, 1972 vs. 2012)

Source: Magazine Publishers of America, http://www.magazine.org, 2012.

| 1972 | 2012 | ||

| Rank/Publication | Circulation | Rank/Publication | Circulation |

| 1 Reader’s Digest | 17,825,661 | 1 AARP The Magazine | 22,625,070 |

| 2 TV Guide | 16,410,858 | 2 AARP Bulletin | 22,343,419 |

| 3 Woman’s Day | 8,191,731 | 3 Game Informer Magazine | 8,016,925 |

| 4 Better Homes and Gardens | 7,996,050 | 4 Better Homes and Gardens | 7,619,247 |

| 5 Family Circle | 7,889,587 | 5 Reader’s Digest | 5,552,450 |

| 6 McCall’s | 7,516,960 | 6 Good Housekeeping | 4,350,749 |

| 7 National Geographic | 7,260,179 | 7 National Geographic | 4,178,679 |

| 8 Ladies’ Home Journal | 7,014,251 | 8 Family Circle | 4,122,460 |

| 9 Playboy | 6,400,573 | 9 People | 3,601,769 |

| 10 Good Housekeeping | 5,801,446 | 10 Woman’s Day | 3,412,086 |

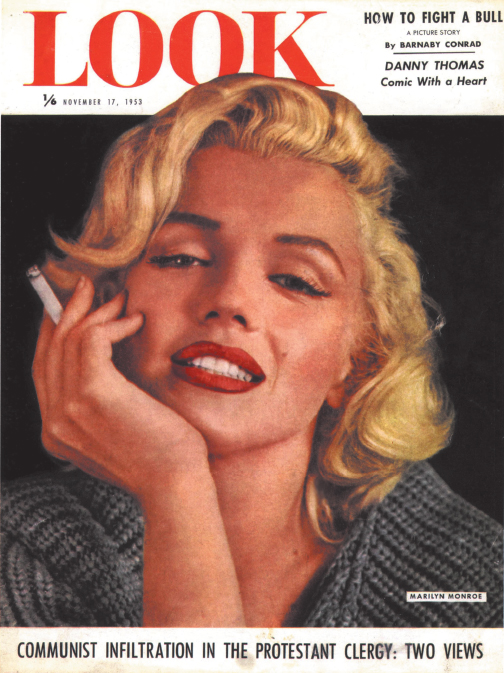

Saturday Evening Post, Life, and Look Expire

With large pages, beautiful photographs, and compelling stories on celebrities like Marilyn Monroe, Look entertained millions of readers from 1937 to 1971, emphasizing photojournalism to compete with radio. By the late 1960s, however, TV lured away national advertisers, postal rates increased, and production costs rose, forcing Look to fold despite a readership of more than eight million.

Although Reader’s Digest and women’s supermarket magazines were not greatly affected by television, other general-interest magazines were. The Saturday Evening Post folded in 1969, Look in 1971, and Life in 1972. At the time, all three magazines were rated in the Top 10 in terms of paid circulation, and each had a readership that exceeded six million per issue. Why did these magazines fold? First, to maintain these high circulation figures, their publishers were selling the magazines for far less than the cost of production. For example, a subscription to Life cost a consumer twelve cents an issue, yet it cost the publisher more than forty cents per copy to make and mail.

Second, the national advertising revenue pie that helped make up the cost differences for Life and Look now had to be shared with network television—and magazines’ slices were getting smaller. Life’s high pass-along readership meant that it had a larger audience than many prime-time TV shows. But it cost more to have a single full-page ad in Life than it did to buy a minute of ad time during evening television. National advertisers were often forced to choose between the two, and in the late 1960s and early 1970s television seemed a better buy to advertisers looking for the biggest audience.

Third, dramatic increases in postal rates had a particularly negative effect on oversized publications (those larger than the 8- by 10.5-inch standard). In the 1970s, postal rates increased by more than 400 percent for these magazines. The Post and Life cut their circulations drastically to save money. The Post went from producing 6.8 million to 3 million copies per issue; Life, which lost $30 million between 1968 and 1972, cut circulation from 8.5 million to 7 million. The economic rationale here was that limiting the number of copies would reduce production and postal costs, enabling the magazines to lower their ad rates to compete with network television. But in fact, with decreased circulation, these magazines became less attractive to advertisers trying to reach the largest general audience.

“At $64,200 for a black-and-white [full] page ad, Life had the highest rate of any magazine, which probably accounts for its financial troubles. … If an advertiser also wants to be on television, he may not be able to afford the periodical.”

JOHN TEBBEL, HISTORIAN, 1969

The general magazines that survived the competition for national ad dollars tended to be women’s magazines, such as Good Housekeeping, Better Homes and Gardens, Family Circle, Ladies’ Home Journal, and Woman’s Day. These publications had smaller formats and depended primarily on supermarket sales rather than on expensive mail-delivered subscriptions (like Life and Look). However, the most popular magazines, TV Guide and Reader’s Digest, benefited not only from supermarket sales but also from their larger circulations (twice that of Life), their pocket size, and their small photo budgets. The failure of the Saturday Evening Post, Look, and Life as oversized general audience weeklies ushered in a new era of specialization.

People Puts Life Back into Magazines

In March 1974, Time Inc. launched People, the first successful mass market magazine to appear in decades. With an abundance of celebrity profiles and human-interest stories, People showed a profit in two years and reached a circulation of more than two million within five years. People now ranks first in revenue from advertising and circulation sales—more than $1.5 billion a year.

The success of People is instructive, particularly because only two years earlier television had helped kill Life by draining away national ad dollars. Instead of using a bulky oversized format and relying on subscriptions, People downsized and generated most of its circulation revenue from newsstand and supermarket sales. For content, it took its cue from our culture’s fascination with celebrities. Supported by plenty of photos, its short articles are about one-third the length of the articles in a typical newsmagazine.

Although People has not achieved the broad popularity that Life once commanded, it does seem to defy the contemporary trend of specialized magazines aimed at narrow but well-defined audiences, such as Tennis World, Game Informer, and Hispanic Business. One argument suggests that People is not, in fact, a mass market magazine but a specialized publication targeting people with particular cultural interests: a fascination with music, TV, and movie stars. If People is viewed as a specialty magazine, its financial success makes much more sense. It also helps explain the host of magazines that try to emulate it, including Us Weekly, Entertainment Weekly, In Touch Weekly, Star, and OK! People has even spawned its own spin-offs, including People en Español and People StyleWatch; the latter is a low-cost fashion magazine that began in 2007 and features celebrity styles at discount prices.