Magazine Departments and Duties

Unlike a broadcast station or a daily newspaper, a small newsletter or magazine can begin cheaply via computer-based desktop publishing, which enables an aspiring publisher-editor to write, design, lay out, and print or post online a modest publication. For larger operations, however, the work is divided into departments.

Editorial and Production

“Inevitably, fashion advertisers that prop up the glossies will, like everyone else, increasingly migrate to Web and mobile interactive advertising.”

ADVERTISING AGE, 2006

The lifeblood of a magazine is the editorial department, which produces its content, excluding advertisements. Like newspapers, most magazines have a chain of command that begins with a publisher and extends to the editor in chief, the managing editor, and a variety of subeditors. These subeditors oversee such editorial functions as photography, illustrations, reporting and writing, copyediting, layout, and print and multimedia design. Magazine writers generally include contributing staff writers, who are specialists in certain fields, and freelance writers, nonstaff professionals who are assigned to cover particular stories or a region of the country. Many magazines, especially those with small budgets, also rely on well-written unsolicited manuscripts to fill their pages. Most commercial magazines, however, reject more than 95 percent of unsolicited pieces.

Despite the rise of inexpensive desktop publishing, most large commercial magazines still operate several departments, which employ hundreds of people. The production and technology department maintains the computer and printing hardware necessary for mass market production. Because magazines are printed weekly, monthly, or bimonthly, it is not economically practical for most magazine publishers to maintain expensive print facilities. As with USA Today, many national magazines digitally transport magazine copy to various regional printing sites for the insertion of local ads and for faster distribution.

Advertising and Sales

“If you don’t acknowledge your magazine’s advertisers, you don’t have a magazine.”

ANNA WINTOUR, EDITOR OF VOGUE, 2000

The advertising and sales department of a magazine secures clients, arranges promotions, and places ads. Like radio stations, network television stations, and basic cable television stations, consumer magazines are heavily reliant on advertising revenue. The more successful the magazine, the more it can charge for advertisement space. Magazines provide their advertisers with rate cards, which indicate how much they charge for a certain amount of advertising space on a page. A top-rated consumer magazine like Sports Illustrated might charge almost $400,000 for a full-page color ad and $116,100 for a third of a page, black-and-white ad. However, in today’s competitive world, most rate cards are not very meaningful: Almost all magazines offer 25 to 50 percent rate discounts to advertisers.11 Although fashion and general-interest magazines carry a higher percentage of ads than do political or literary magazines, the average magazine contains about 45 percent ad copy and 55 percent editorial material, a figure that has remained fairly constant for the past decade.

The traditional display ad has been the staple of magazine advertising for more than a century. As magazines move to tablet editions, the options for ad formats has grown immensely. For example, Condé Nast magazines offer static display ads with a link for its editions on the iPad, Kindle Fire, Nexus 7, and Surface. But they offer almost thirty other premium ad types, which can include audio, video, tap and reveal, and panoramic views. A single issue static page ad in tablet editions of titles like GQ, Wired, Vanity Fair, the New Yorker, and Vogue would cost $5,000. A premium ad with effects such as animation or a slide show costs $25,000, while a premium plus ad with effects like a virtual tour or full interactivity costs $45,000. (The cost per ad is discounted with purchases of multiple issues.)

A few contemporary magazines, such as Highlights for Children, have decided not to carry ads and rely solely on subscriptions and newsstand sales instead. To protect the integrity of their various tests and product comparisons, Consumer Reports and Cook’s Illustrated carry no advertising. To strengthen its editorial independence, Ms. magazine abandoned ads in 1990 after years of pressure from the food, cosmetics, and fashion industries to feature recipes and more complementary copy.

“So … the creative challenge, especially when you work for a bridal magazine, is how do we keep this material fresh? How do we keep it relevant? How do we, you know, get the reader excited, keep ourselves excited?”

DIANE FORDEN, EDITOR IN CHIEF, BRIDAL GUIDE MAGAZINE, 2004

Some advertisers and companies have canceled ads when a magazine featured an unflattering or critical article about a company or an industry.12 In some instances, this practice has put enormous pressure on editors not to offend advertisers. The cozy relationships between some advertisers and magazines have led to a dramatic decline in investigative reporting, once central to popular magazines during the muckraking era.

As television advertising siphoned off national ad revenues in the 1950s, magazines began introducing different editions of their magazines to attract advertisers. Regional editions are national magazines whose content is tailored to the interests of different geographic areas. For example, Sports Illustrated often prints five different regional versions of its College Football Preview and March Madness Preview editions, picturing regional stars on each of the five covers. In split-run editions, the editorial content remains the same, but the magazine includes a few pages of ads purchased by local or regional companies. Most editions of Time and Sports Illustrated, for example, contain a number of pages reserved for regional ads. Demographic editions, meanwhile, are editions of magazines targeted at particular groups of consumers. In this case, market researchers identify subscribers primarily by occupation, class, and zip code. Time magazine, for example, developed special editions of its magazine for top management, high-income zip-code areas, and ultrahigh-income professional/managerial households. Demographic editions guarantee advertisers a particular magazine audience, one that enables them to pay lower rates for their ads because the ads will be run only in a limited number of copies of the magazine. The magazine can then compete with advertising in regional television or cable markets and in newspaper supplements. Because of the flexibility of special editions, new sources of income opened up for national magazines. Ultimately, these marketing strategies permitted the massive growth of magazines in the face of predictions that television would cripple the magazine industry.

Circulation and Distribution

The circulation and distribution department of a magazine monitors single-copy and subscription sales. Toward the end of the general-interest magazine era in 1950, newsstand sales accounted for about 43 percent of magazine sales, and subscriptions constituted 57 percent. Since that time, subscriptions have risen to 73 percent of magazine sales. One tactic used by magazines’ circulation departments to increase subscription sales is to encourage consumers to renew well in advance of their actual renewal dates. Magazines can thus invest and earn interest on early renewal money as a hedge against consumers who drop their subscriptions.

Other strategies include evergreen subscriptions—those that automatically renew on a credit card account unless subscribers request that the automatic renewal be stopped—and controlled circulations, providing readers with the magazine at no charge by targeting captive audiences such as airline passengers or association members. These magazines’ financial support comes solely from advertising or corporate sponsorship.

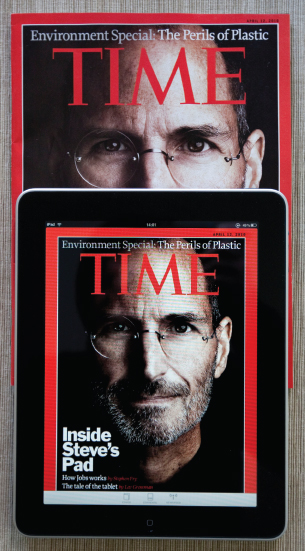

The biggest strategy for reviving magazine sales is the migration to digital distribution (which also promises savings over the printing and physical distribution of glossy paper magazines). The number of magazines with iPad apps (which enable users to click on the app and launch the magazine) has grown rapidly, but publishers and customers alike have complained about Apple’s initial requirements, which permitted only the sale of single issues and only through their iTunes App Store. Apple also declined to share subscriber information with publishers, and, as with the sales of songs in iTunes, Apple would keep a 30-percent cut of each transaction. Magazine publishers didn’t like Apple’s big share of profits and lack of marketing information about their readers, and readers didn’t like the high price of buying single issues through the App Store.13

Although the iPad still reigns supreme in the world of tablets, other touchscreen color tablets, like the Amazon Kindle Fire, the Google Nexus 7, and the Samsung Galaxy Tab, have offered competition in the expanding market. Moreover, Google tried out OnePass, an alternative payment system that takes only a 10-percent cut of the sale price and shares subscriber information with the publisher. By the summer of 2011, Apple recognized that it had to adjust its rules, and began offering publishers some subscriber information and allowing them to sell subscriptions. Other models, such as the Next Issue Media app, offer more than forty titles for a subscription fee of $9.99 to $14.99 a month—a plan like Netflix, but for magazines.