Social Reform and the Muckrakers

Better distribution and lower costs had attracted readers, but to maintain sales, magazines had to change content as well. While printing the fiction and essays of the best writers of the day was one way to maintain circulation, many magazines also engaged in one aspect of yellow journalism—crusading for social reform on behalf of the public good. In the 1890s, for example, Ladies’ Home Journal (LHJ) and its editor, Edward Bok, led the fight against unregulated patent medicines (which often contained nearly 50 percent alcohol), while other magazines joined the fight against phony medicines, poor living and working conditions, and unsanitary practices in various food industries.

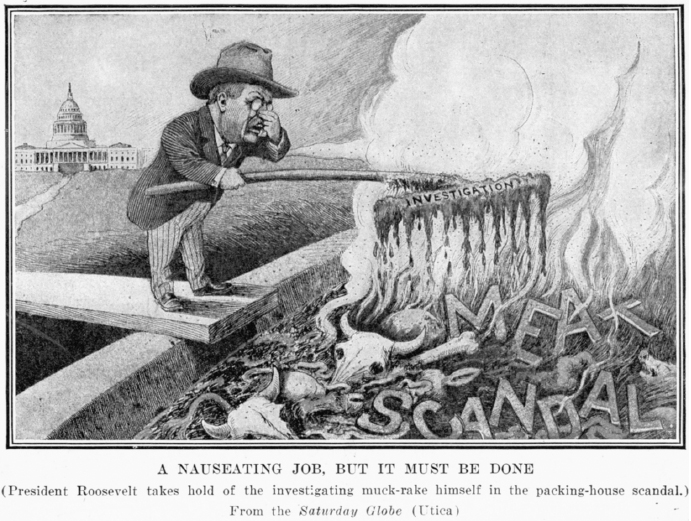

“Men with the muckrake are often indispensable to the well-being of society, but only if they know when to stop raking the muck.”

TEDDY ROOSEVELT, 1906

The rise in magazine circulation coincided with rapid social changes in America. While hundreds of thousands of Americans moved from the country to the city in search of industrial jobs, millions of new immigrants also poured in. Thus, the nation that journalists had long written about had grown increasingly complex by the turn of the century. Many newspaper reporters became dissatisfied with the simplistic and conventional style of newspaper journalism and turned to magazines, where they were able to write at greater length and in greater depth about broader issues. They wrote about such topics as corruption in big business and government, urban problems faced by immigrants, labor conflicts, and race relations.

“Ford gave Everyman a car he could drive, [and] Wallace gave Everyman some literature he could read; both turned the trick with mass production.”

JOHN BAINBRIDGE, MAGAZINE HISTORIAN, 1945

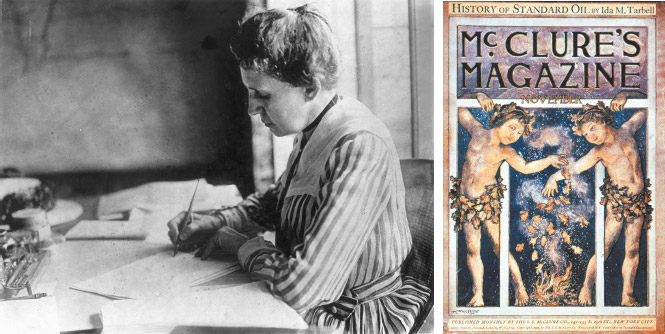

In 1902, McClure’s magazine (1893–1933) touched off an investigative era in magazine reporting with a series of probing stories, including Ida Tarbell’s “The History of the Standard Oil Company,” which took on John D. Rockefeller’s oil monopoly, and Lincoln Steffens’s “Shame of the Cities,” which tackled urban problems. In 1906, Cosmopolitan magazine joined the fray with a series called “The Treason of the Senate,” and Collier’s magazine (1888–1957) developed “The Great American Fraud” series, focusing on patent medicines (whose ads accounted for 30 percent of the profits made by the American press by the 1890s). Much of this new reporting style was critical of American institutions. Angry with so much negative reporting, in 1906 President Theodore Roosevelt dubbed these investigative reporters muckrakers, because they were willing to crawl through society’s muck to uncover a story. Muckraking was a label that Roosevelt used with disdain, but it was worn with pride by reporters such as Ray Stannard Baker, Frank Norris, and Lincoln Steffens.

Influenced by Upton Sinclair’s novel The Jungle—a fictional account of Chicago’s meatpacking industry—and by the muckraking reports of Collier’s and LHJ, in 1906 Congress passed the Pure Food and Drug Act and the Meat Inspection Act. Other reforms stemming from muckraking journalism and the politics of the era include antitrust laws for increased government oversight of business, a fair and progressive income tax, and the direct election of U.S. senators.