Monitoring the Advertising Industry

Printed Page 346

Worried about advertising’s power over vulnerable consumers, a few nonprofit watchdog and advocacy organizations, such as Commercial Alert and the American Legacy Foundation, have emerged. Such groups strive to compensate for some of the shortcomings of the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and other government agencies in monitoring false and deceptive ads and the excesses of commercialism. At the same time, the FTC is still trying to combat the negative impact of advertising, though its effectiveness remains questionable, especially in light of cutbacks at the agency that have been going on since the 1980s.

Commercial Alert

Since 1998, Commercial Alert has worked to “limit excessive commercialism in society.” Founded in part with help from longtime consumer advocate Ralph Nader, Commercial Alert became a project of Public Citizen, a nonprofit consumer protection organization based in Washington, D. C. In addition to trying to check commercialism, Commercial Alert has challenged specific marketing tactics that allow corporations to intrude into civic life. For example, in 2012 Commercial Alert objected to the state of Kentucky’s proposal to sell advertising on school buses. The group argued that “children need a sanctuary from a world where everything seems to be for sale.” In constantly questioning the role of advertising in our democracy, Commercial Alert has aimed to strengthen noncommercial culture and limit the amount of corporate influence on publicly elected government officials and organizations.

The American Legacy Foundation

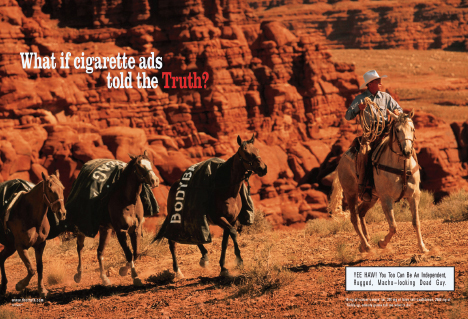

Some nonprofit organizations have used innovative advertising of their own to offset the effects of ads for dangerous products. For example, in 2000, the American Legacy Foundation launched an antismoking/antitobacco–industry ad campaign called “Truth.” The campaign’s mission has been to counteract tobacco marketing and reduce tobacco use among young people. The “Truth” project uses print and television ads that contradict the images that have long been featured in cigarette ads. For example, one spot shows a giant rat expiring on a city sidewalk, clutching a cardboard sign saying that cigarettes contain the same chemical found in rat poison. All “Truth” spots prominently reference the foundation’s Web site, thetruth.com, which offers statistics, discussion forums, and outlets for teen creativity, such as games.

The FTC

Through its truth-in-advertising rules, the FTC has played an investigative role in substantiating the claims of various advertisers. Thus the organization contributes to some regulation of the ad industry. The FTC usually permits a certain amount of puffery—ads featuring hyperbole and exaggeration—particularly when an ad describes a product as “new and improved.” However, the FTC defines ads as deceptive when they are likely to mislead reasonable consumers through statements made, images shown, or omission of certain information. (For example, in some Campbell Soup ads once featuring images of a bowl of soup, marbles had been placed in the bottom of the bowl to push bulkier ingredients to the surface. This was deceptive advertising because it made the soup look less watery than it really was.) Moreover, when an advertiser makes comparative claims for a product, such as it’s “the best,” “the greatest,” or “preferred by four out of five doctors,” FTC rules require statistical evidence to back up the claims.

When the FTC discovers deception in advertising, it usually requires advertisers to change or remove the ads from circulation. The FTC can also impose monetary civil penalties, which are paid to consumers. And it occasionally requires an advertiser to run spots correcting the deceptive ads.