Retail Stores: Giving Birth to Branding

Printed Page 324

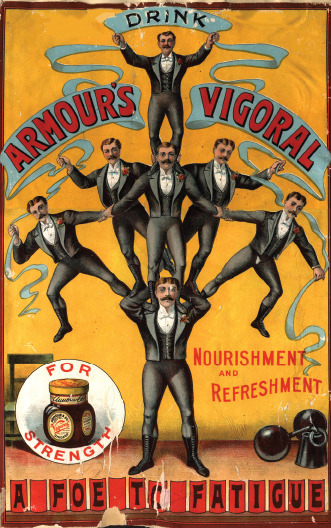

During the mid-1800s, most manufacturers sold their goods directly to retail store owners, who usually set their own prices by purchasing products in large quantities. Stores would then sell these loose goods—from clothing to cereal—in large barrels and bins, so customers had no idea who made them. This arrangement shifted after manufacturers started using newspaper advertising to create brand names—that is, to differentiate their offerings and their company’s image from those of their competitors in the minds of consumers and retailers—even if the goods were basically the same. For example, one of the earliest brand names, Quaker Oats (the first cereal company to register a trademark in the 1870s) used the image of William Penn, the Quaker who founded Pennsylvania in 1681, in its ads to project a company image of honesty, decency, and hard work.

Consumers, convinced by the ads, began demanding certain products. And retail stores felt compelled to stock the desired brands. This enabled manufacturers, not the retailers, to begin setting the prices of their goods—confident that they’d prevail over the stores’ anonymous, bulk items. Indeed, product differentiation in brand-name packaged goods represents advertising’s single biggest triumph. Though most ads don’t trigger a large jump in sales in the short run, over time they create demand by leading consumers to associate particular brands with qualities and values important to them.