A Closer Look at Public Relations Functions

Printed Page 364

Regardless of whether they work at a PR agency or on staff at an organization’s in-house PR department, public relations professionals pay careful attention to the needs of their clients and to the perspectives of their targeted audiences. They provide a multitude of services, including developing publicity campaigns and formulating messages about what their clients are doing in areas such as government relations, community outreach, industry relations, diversity initiatives, and product or service development. Some PR professionals also craft propaganda. This is communication that is presented as advertising or publicity and that is intended to gain (or undermine) public support for a special issue, program, or policy—such as a nation’s war effort (see “Converging Media Case Study: YouTube and Wartime PR”). In addition, PR practitioners might produce employee newsletters, manage client trade shows and conferences, conduct historical tours, appear on news programs, organize damage control after negative publicity, or analyze complex issues and trends affecting a client’s future.

Research: Formulating the Message

Like advertising, PR makes use of mail, telephone, Internet surveys, and focus groups to get a fix on an audience’s perceptions of an issue, a policy, a program, or a client’s image. This research also helps PR firms focus their campaign messages. For example, the Liz Claiborne Foundation has tried to combat domestic violence (specifically, teen dating abuse) by using survey results from 683 teens to develop its “Love Is Not Abuse” campaign.

Communication: Conveying the Message

Once a PR group has formulated a message, it conveys the message through a variety of channels. With advances in digital technology, these channels have become predominantly Internet-based in recent years. Press releases, or news releases, are announcements written in the style of news reports that provide new information about an individual, a company, or an organization, now typically issued via e-mail. In issuing press releases, PR agents hope that journalists will pick up the information and transform it into news reports about the agents’ clients.

Since the introduction of portable video equipment in the 1970s, PR agencies and departments have also been issuing video news releases (VNRs)—thirty- to ninety-second visual press releases designed to mimic the style of a broadcast news report. Although networks and large TV news stations do not usually broadcast VNRs, news stations in small TV markets regularly use material from these releases, which can also be sent to editors of well-trafficked blogs and other Web sites, or displayed independently online. As with press releases, VNRs give PR firms some control over what constitutes “news” and a chance to influence the public’s opinions about an issue, a program, or a policy, although the FCC requires that the source of a VNR be disclosed if video from the VNR is broadcast in a news program.

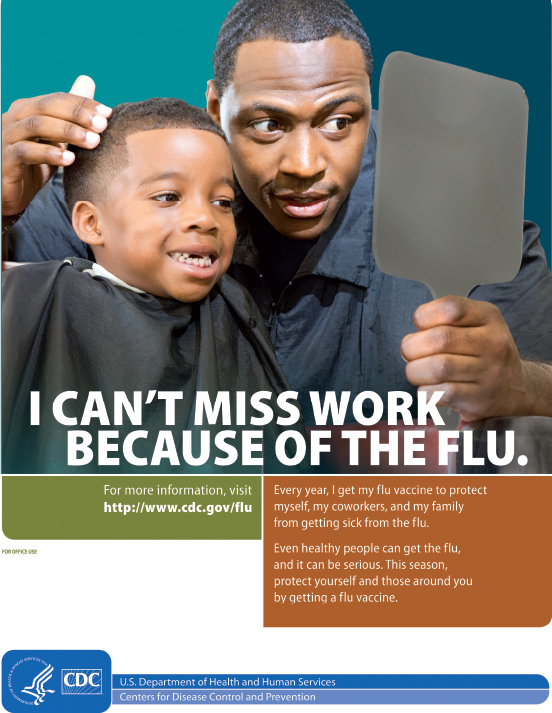

PR firms can also bring attention to nonprofits by creating public service announcements (PSAs): usually fifteen- to sixty-second audio or video reports that promote government programs, educational projects, volunteer agencies, or social reform.

The Internet has also become an essential avenue for transmitting PR messages. Public relations practitioners use the Internet to send electronic press releases and VNRs, make press kits available for downloading, post YouTube videos, and host PR-based Web sites (for instance, the official Web sites of political candidates).

The Web also enables PR professionals to have their clients interact with audiences on a more personal, direct basis through social media tools like Facebook, Twitter, Wikipedia, and blogs. Executives, celebrities, and politicians can seem more accessible and personable through a Twitter feed. The immediacy of social media also means that public relations professionals might be forced to respond more quickly and decisively to a message or an image once it goes viral. The Internet and social media also complicate the traditional PR relationship of an organization to its publics: Now potentially anyone connected to the Internet can be one of the “publics” that interact with the organization.

Managing Media Relations

Some PR practitioners specialize in media relations. They promote a client or an organization by securing publicity or favorable coverage in the various news media. In an in-house PR department, media-relations specialists will speak on behalf of their organization or direct reporters to experts inside and outside the company who can provide information about whatever topic the reporter is writing about.

Media-relations specialists may also recommend advertising to their clients when it seems that ads would help focus a complex issue or enhance a client’s image. In addition, they cultivate connections with editors, reporters, freelance writers, and broadcast news directors to ensure that their press releases or VNRs are favorably received. (See “Media Literacy Case Study: Improving the Credibility Gap”.)

If a client company has had some negative publicity (for example, one of its products has been shown to be defective or dangerous, or a viral video on the Internet quickly spreads disinformation about the company), media-relations specialists also perform damage control or crisis management. In fact, during a crisis, these specialists might be the sole source of information about the situation for the public. How PR professionals perform this part of their job can make or break an organization. The handling of the Exxon Valdez oil spill and Tylenol tampering deaths in the 1980s offer two contrasting examples.

In 1989, the Exxon Valdez oil tanker spilled eleven million gallons of crude oil into Prince William Sound. The accident contaminated fifteen hundred miles of Alaskan coastline and killed countless birds, otters, seals, and fish. In one of the biggest PR blunders of that century, Exxon reacted to the crisis grudgingly and accepted responsibility slowly. Although the company’s PR advisers had advised a quick response, Exxon failed to send any of its chief officers immediately to the site—a major gaffe. Many critics believed that Exxon was trying to duck responsibility by laying the burden of the crisis on the shoulders of the tanker’s captain. Even though the company changed the name of the tanker to Mediterranean and implemented other strategies intended to salvage the company’s image, the public continued to view Exxon in a negative light. BP had a similar public relations failure following a deadly oil rig explosion and massive oil leak in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010.

A decidedly different approach was taken in the 1982 tragedy involving Tylenol pain-relief capsules. Seven people in the Chicago area died after consuming capsules that someone had laced with poison. The parent company, Johnson & Johnson, and its PR representatives discussed whether to pull all Tylenol capsules from store shelves. Some participants in these discussions worried that this move might send the message that corporations could be intimidated by a single deranged person. Nevertheless, Johnson & Johnson’s chairman and the company’s PR agency, Burson-Marsteller, opted to fully disclose the tragedy to the media and to immediately recall all Tylenol capsules across the nation. The recall cost the company an estimated $100 million and cut its market share in half.

Burson-Marsteller tracked public opinion about the crisis and about its client nightly through telephone surveys. It also organized satellite press conferences to debrief the news media. In addition, it set up emergency phone lines to take calls from consumers and health-care providers who had questions about the crisis. When the company reintroduced Tylenol three months later, it did so with tamper-resistant bottles that almost every major drug manufacturer soon copied. According to Burson-Marsteller, which received PRSA awards for its handling of the crisis, the public thought Johnson & Johnson had responded admirably to the situation and did not hold Tylenol responsible for the deaths. In fewer than three years, Tylenol recaptured its dominant share of the market.

Coordinating Special and Pseudo Events

Another public relations practice involves coordinating special events to raise the profile of corporate, organizational, or government clients. Through such events, a corporate sponsor aligns itself with a cause or an organization that has positive stature among the public. For example, John Hancock Financial has been the primary sponsor of the Boston Marathon since 1986 and provides the race’s prize money.

In contrast to a special event, a pseudo event is any circumstance created for the sole purpose of gaining coverage in the media. Pseudo events may take the form of press conferences, TV and radio talk-show appearances, or any other staged activity aimed at drawing public attention and media coverage. Clients and sometimes paid performers participate in these events, and their success is strongly determined by how much media attention the event attracts. For example, during the 1960s, antiwar and Civil Rights activists staged protest events only if news media were assembled.

Fostering Positive Community and Consumer Relations

Another responsibility of PR practitioners is to sustain goodwill between their clients and the public. Many public relations professionals define “the public” as consisting of two distinct audiences: communities and consumers. Thus they carefully manage relations with both groups.

PR specialists let the public know that their clients or companies are valuable members of the communities in which they operate. They design opportunities for their clients to demonstrate that they are good citizens. For example, they arrange for client firms to participate in community activities such as hosting plant tours and open houses, making donations to national and local charities, participating in town events like parades and festivals, and allowing employees to take part in local fund-raising drives for good causes.

PR strategists also strive to show that their clients care about their customers. For example, a PR campaign might send the message that the business has established product-safety guarantees, or that the company will answer all calls and mail from customers promptly. These efforts result in satisfied customers, which translates into repeat business and new business, as customers spread the word about their positive experiences with the organization.

Cultivating Government Relations

PR groups working for or in corporations also cultivate connections with the government agencies that have some say in how companies operate in a particular community, state, or nation. Through such connections, these groups can monitor the regulatory environment and determine new laws’ potential implications for the organization’s they represent. For example, a new regulation might require companies to provide more comprehensive reporting on their environmental-safety practices, which would represent an added responsibility.

Government PR specialists monitor new and existing legislation, look for opportunities to generate favorable publicity, and write press releases and direct-mail letters to inform the public about the pros and cons of new regulations. In many industries, government relations has developed into lobbying: the process of trying to influence lawmakers to support legislation that would serve an organization’s or industry’s best interests. In seeking favorable legislation, some lobbyists contact government officials on a daily basis. In Washington, D.C., alone, there are about twelve thousand registered lobbyists, and lobbying expenditures targeting the federal government rose to $3.5 billion in 2010, up from $1.56 billion ten years earlier.5

The millions of dollars that lobbyists inject into the political process—treating lawmakers to special events and campaign contributions in return for legislation that accommodates their clients’ interests—is viewed by many as unethical. Another unethical practice is astroturf lobbying, which consists of phony grassroots public-affairs campaigns engineered by unscrupulous public relations firms. Through this type of lobbying, PR firms deploy blogs, social media campaigns, massive phone banks, and computerized mailing lists to drum up support and create the impression that millions of citizens back their client’s side of an issue—even if the number is much lower.

Just as corporations use PR to manage government relations, some governments have used PR to manage their image in the public’s mind. For example, following the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the United States, the Saudi Arabian government hired the PR firm Qorvis Communications to help repair its image with American citizens after it was revealed that many of the 9/11 terrorists were from Saudi Arabia.6