14

Legal Controls and Freedom of Expression

Printed Page 414

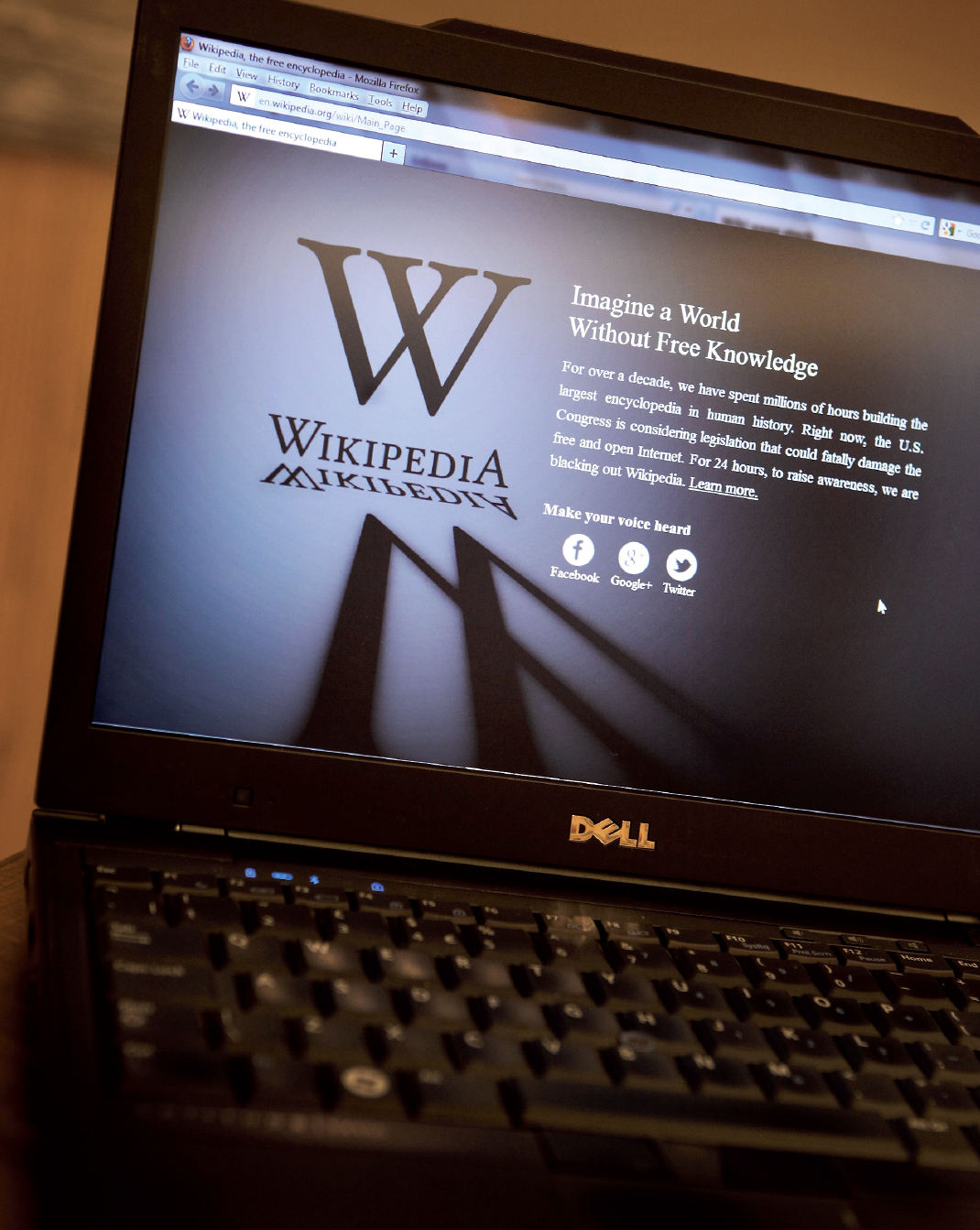

On January 18, 2012, anyone visiting the popular Web site Wikipedia was met with a blackout: An estimated 160 million visitors saw none of the site’s usual encyclopedic entries or search function, only a message asking people to “Imagine a world without free knowledge.” Internet users looking for access to sites like Reddit, Twitpic, and Mozilla found similar messages; they were just a few of the more than 115,000 Web sites that participated in protesting the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA), a bill under consideration in Congress that would expand governmental powers to combat copyright infringement on the Internet. The centerpiece of the protest was Wikipedia’s blacking out of its English-language site for twenty-four hours, advocating that users consider the consequences of this bill. The protest resulted in 3 million people e-mailing Congress to register opposition to SOPA and a similar bill being considered in the Senate—the Protect Intellectual Property Act (PIPA).1

Both SOPA and PIPA were pushed by old media powers that comprise the copyright lobby (including the Motion Picture Association of America, the Recording Industry Association of America, and an array of other companies in the music, television, film, and publishing industries). Supporters of the legislation claimed they were only trying to go after foreign sites that sell pirated copies of software, videos, and music.

The new media opponents of the bill, many associated with popular sites featuring a mix of preexisting and user-generated content, took issue with how the old media hoped to strengthen the law’s enforcement. The proposed law would have enabled copyright holders to block Web sites, censor search results, and cut off advertising revenue without even going through a judge. Some feared that the language of the law was so vague that one violation could result in the shutting down of an entire domain. Others argued the costs of complying with the law would have a chilling effect on the Internet economy by discouraging investors from developing new businesses.

The most relevant opposition to SOPA involved questions of censorship. Lawrence H. Tribe, a professor of constitutional law at Harvard University, wrote in a letter to Congress that SOPA’s “very existence would dramatically chill protected speech by undermining the openness and free exchange of information at the heart of the internet.” 2 International responses also condemned the legislation as a form of censorship. The European Union Parliament adopted a resolution that stressed “the need to protect the integrity of the global internet and freedom of communication by refraining from unilateral measures to revoke IP addresses or domain names.” 3

SUCH DEBATES OVER WHAT CONSTITUTES “FREE SPEECH” or “free expression” have intensified as technological advances enable easy creation of new types of media content. The questions explored in such debates center on two themes: economics and politics. For example, arguments about what constitutes copyright violation revolve around who should be allowed to make money from the creation, distribution, and ownership of media content—and who should shoulder the expense of enforcing copyright law. Meanwhile, debates about the particular messages in a piece of media content raise questions about politics. For instance, do teenagers have a right to use social media to bully a person because of his or her sexual orientation? Do military secrets published on the Internet prevent the government from protecting the citizenry?

Such arguments also raise questions regarding the variation in regulatory standards that has evolved across different mass media. For example, print media have the least regulation, as the First Amendment clearly protects freedom of the press. Broadcast has the strictest regulation, as lawmakers have defined the airwaves as a shared public resource. And regulation regarding the Internet is contested, as the technology (and the different ways in which people and organizations use it) is still comparatively new.

In this chapter, we examine these themes more closely by:

- exploring the origins of free expression and a free press, identifying four models of free expression, taking a closer look at the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, tracing the emergence of censorship, and comparing the First Amendment with the Sixth Amendment

- shining a spotlight on film and the First Amendment, assessing social and political pressures affecting moviemaking, self-regulation in the film industry, and the emergence of the film-ratings system

- taking stock of free expression in the broadcast and online media, including examining the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) regulation of broadcasting, definitions and regulation of indecent speech, laws governing political broadcasts, the impact of the Fairness Doctrine, and communication policy regarding the Internet

- considering the First Amendment’s role in our democracy today, including questions such as who (journalists? citizens? both?) should fulfill the civic role of watchdog