Unprotected Forms of Expression

Printed Page 422

Despite the First Amendment’s provision that “Congress shall make no law” restricting speech and the press, the federal government, state laws, and even local ordinances have on occasion curbed some forms of expression. And over the years, the U.S. court system has determined that some kinds of expression do not merit protection under the Constitution. These forms include sedition, copyright infringement, libel, obscenity, and violation of privacy rights.

Sedition

For more than a century after the Sedition Act of 1798, Congress passed no laws prohibiting the articulation or publication of dissenting opinions. But sentiments that fueled the Sedition Act resurfaced in the twentieth century, particularly in times of war. For instance, the Espionage Acts of 1917 and 1918, enforced during the two world wars, made it a federal crime to utter or publish “seditious” statements, defined as anything expressing opposition to the U.S. war effort.

For example, in the landmark Schenck v. United States (1919) appeal case, held during World War I, the Supreme Court upheld the conviction of a Socialist Party leader, Charles T. Schenck, for distributing leaflets urging American men to protest the draft. Justices argued that Schenck had violated the recently passed Espionage Act.

In supporting Schenck’s sentence—a ten-year prison term—Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes noted that the Socialist leaflets were entitled to First Amend-ment protection, but only during times of peace. In establishing the “clear and present danger” criterion for expression, the Supreme Court demonstrated the limits of the First Amendment.

Copyright Infringement

Appropriating a writer’s or an artist’s words, images, or music without consent or payment is also a form of expression not protected by the First Amendment. A copyright legally protects the rights of authors and producers to their published or unpublished writing, music, lyrics, TV programs, movies, or graphic-art designs. Congress passed the first Copyright Act in 1790, which gave authors the right to control their published works for fourteen years, with the opportunity to renew copyright protection for another fourteen years. After the end of the copyright period, the work would enter the public domain, which would give the public free access to the work. (For example, a publisher could reprint a written work that had entered the public domain.) The idea was that a period of copyright control would give authors financial incentive to create original works, and that moving works into the public domain would give others incentive to create works derived from earlier accomplishments.

But in time, artists, as they began to live longer, and corporations, which could also hold copyrights, wanted to prolong the period in which they could profit from creative works. In 1976 Congress extended the copyright period to the life of the author plus fifty years (seventy-five years for a corporate copyright owner). In 1998 (as copyrights on works such as Disney’s Mickey Mouse were set to expire), Congress again extended the copyright period for twenty additional years.

Today, nearly every innovation in digital culture creates new questions about copyright law. For example, is a video remix that samples copyrighted sounds and images a copyright violation or a creative accomplishment protected under the concept of fair use (the same standard that enables students to legally quote attributed text in their research papers)? One of the laws that tips the debates toward stricter enforcement of copyright is the Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998, which outlaws technology or actions that circumvent copyright systems. In other words, it may be illegal merely to create or distribute technology that enables someone to make illegal copies of digital content, such as a movie DVD.

The copyright lobby continues to pressure lawmakers to enact measures that would criminalize infringement. Legislation first proposed in 2011 would hold online service providers like YouTube, Internet search engines like Google, and payment service providers like Paypal accountable for policing their users and enforcing U.S. intellectual property law globally. As manifested in the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA) and Protect Intellectual Property Act (PIPA), this legislation has prompted recent worldwide protests, which have, as mentioned in the opening of this chapter, derailed the proposed bills—at least temporarily. Both sides of the piracy struggle recognize that the SOPA/PIPA conflict is just a skirmish in a much longer engagement over the future of free expression on the Internet.

Libel

The biggest legal worry haunting editors and publishers today is the possibility of being sued for libel, a form of expression that, unlike political speech, is not protected under the First Amendment.Libel is defamation of someone’s character in written or broadcast form. It differs from slander, which is spoken defamation. Inherited from British common law, libel is generally defined as a false statement that holds a person up to public ridicule, contempt, or hatred or that injures a person’s business or livelihood. Examples of potentially libelous statements include falsely accusing someone of professional incompetence (such as medical malpractice); falsely accusing a person of a crime (such as drug dealing); falsely stating that someone is mentally ill or engages in unacceptable behavior (such as public drunkenness); and falsely accusing a person of associating with a disrepu-table organization or cause (such as being a member of the Mafia or a neo-Nazi military group). (See “Media Literacy Case Study: A False Wikipedia ‘Biography’.”)

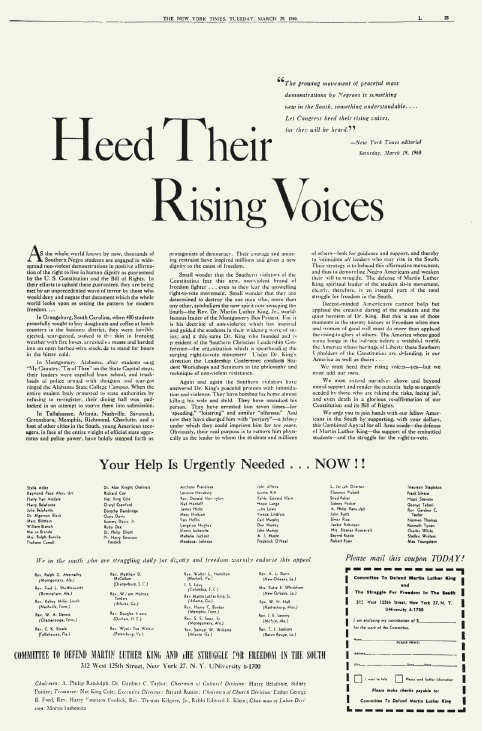

Since 1964, The New York Times v. Sullivan case has served as the standard for libel law. The case stems from a 1960 full-page advertisement placed in the New York Times by the Committee to Defend Martin Luther King and the Struggle for Freedom in the South. Without naming names, the ad criticized the law-enforcement tactics used in southern cities to break up Civil Rights demonstrations. The city commissioner of Montgomery, Alabama, L. B. Sullivan, sued the Times for libel, claiming the ad defamed him indirectly. Alabama civil courts awarded Sullivan $500,000, but the Times’ lawyers appealed to the Supreme Court. The Court reversed the ruling, holding that Alabama libel law violated the Times’ First Amendment rights.8

Private individuals (such as city sanitation employees, undercover police informants, or nurses) must prove three things to win a libel case: (1) that the public statement about them was false; (2) that damages or actual injury occurred (such as loss of a job, or mental anguish); and (3) that the publisher or broadcaster was negligent in failing to determine the truthfulness of the statement.

In the Sullivan case, the Supreme Court asked future civil courts to distinguish whether plaintiffs in libel cases are “public officials” or “private individuals.” To win libel cases, the Court said, public officials (such as movie or sports stars, political leaders, or lawyers defending a prominent client) are held to a tougher standard, and must prove falsehood, damages, negligence, and actual malice on the part of the news media. Actual malice means that the reporter or editor knew the statement was false and printed or broadcast it anyway, or acted with a reckless disregard for the truth. Because actual malice against a public official is hard to prove, it is difficult for public figures to win libel suits.

Historically, the best defense against libel in American courts has been the truth. In most cases, if libel defendants can demonstrate that they printed or broadcast true statements, plaintiffs will not recover any damages—even if their reputations were harmed. There are other defenses against libel as well. For example, prosecutors (who would otherwise be vulnerable to accusations of libel) are granted absolute privilege in a court of law so they can freely make accusatory statements toward defendants—a key part of their job. Reporters who print or broadcast statements made in court are also protected against libel.

Another defense against libel is the rule of opinion and fair comment, the notion that libel consists of intentional misstatements of factual information, not expressions of opinion. However, the line between fact and opinion is often blurry. For instance, one of the most famous tests of opinion and fair comment came with a case pitting conservative minister and political activist Jerry Falwell against Larry Flynt, publisher of Hustler, a pornographic magazine. The case developed after a spoof ad in the November 1983 issue of Hustler suggested that Falwell had had sex with his mother. Falwell sued for libel, demanding $45 million in damages. The jury rejected the libel suit but found that Flynt had intentionally caused Falwell emotional distress—and awarded Falwell $200,000. Flynt’s lawyers appealed, and the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the verdict in 1988, explaining that the magazine was entitled to constitutional protection.

Libel laws also protect satire, comedy, and opinions expressed in reviews of books, plays, movies, and restaurants. However, such laws do not protect malicious statements in which plaintiffs can prove that defendants used their free-speech rights to mount an uncalled-for damaging personal attack.

Obscenity

For most of this nation’s history, legislators have argued that obscenity is not a form of expression protected by the First Amendment. However, experts have not been able to agree on what constitutes an obscene work, especially as definitions of obscenity have changed over the years. For example, during the 1930s, novels (such as James Joyce’s Ulysses) were judged obscene if they contained “four-letter words.”

The current legal definition of obscenity, derived from the 1973 Miller v. California case, states that obscene materials meet three criteria: (1) the average person, applying contemporary community standards, finds the material as a whole appeals to prurient interest (i.e., incites lust); (2) the material depicts or describes sexual conduct in a patently offensive way; and (3) the material, as a whole, lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value. The Miller decision acknowledged that different communities and regions of the country have different standards with which to judge obscenity. It also required that a work be judged as a whole. This was designed to keep publishers from simply inserting a political essay or literary poem into pornographic materials to demonstrate that their publication contained redeeming features.

Since the Miller decision, major prosecutions of obscenity have been rare, and most battles now concern the Internet, where the concept of community standards has been eclipsed by this medium’s global reach. The most recent incarnation of the Child Online Protection Act—originally formed in 1998 to make it illegal to post “material that is harmful to minors”—was found unconstitutional in 2007 because it infringed on the right to free speech online. The presiding judge in this decision also stated that the act would be ineffective, as it wouldn’t apply to pornographic Web sites from overseas, which account for up to half of such sites. The ruling suggested that parents and software filters offer the best protection for children against harmful content on the Web.

Violation of Privacy Rights

Whereas libel laws safeguard a person’s character and reputation, the right to privacy protects an individual’s peace of mind and personal feelings. In the simplest terms, the right to privacy addresses a person’s right to be left alone, without his or her name, image, or daily activities becoming public property. The most common forms of privacy invasion are unauthorized tape recording, photographing, and wiretapping of someone; making someone’s personal records such as health and phone records available to the public; disclosing personal information such as religious or sexual activities; and appropriating (without authorization) someone’s image or name for advertising or other commercial purposes.

In general, the news media have been granted wide protections under the First Amendment to do their work even if it approaches or constitutes violation of privacy. For instance, journalists can typically use the names and pictures of private individuals and public figures without their consent in their news stories. Still, many local municipalities and states have passed “anti-paparazzi” laws protecting public individuals from unwarranted scrutiny and surveillance on their private property. A number of laws also protect regular citizens’ privacy. For example, the Privacy Act of 1974 protects individuals’ records from public disclosure unless they give written consent. In some cases, however, private citizens become public figures—for example, rape victims who are covered in the news. In these situations, reporters have been allowed to record these individuals’ quotes and use their images without permission.

The Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986 extended the law regarding private citizens to computer-stored data and the Internet, including employees’ e-mails composed and sent through their employer’s equipment. However, subsequent court decisions ruled that employees have no privacy rights in electronic communications conducted on their employer’s equipment. The USA PATRIOT Act of 2001 further weakened the earlier laws, giving the federal government more latitude in searching private citizens’ records and intercepting electronic communications without a court order.

Congress made a step toward bringing more Internet privacy to Americans by proposing the Do Not Track Me Online Act of 2011. It would give consumers the ability to opt out of having their online activity collected by private companies without their permission. But in a society that is both fiercely defensive of its privacy and widely engaged in sharing more personal information than in any other period in history, it remains unclear how individual privacy will be legally controlled in the digital age.