Conducting Social Scientific Media Research

Printed Page 486

As researchers investigated various theories about how media affect people, they also developed different approaches to conducting their research. These approaches vary depending on whether the research originates in the private or public sector. Private research, sometimes called proprietary research, is generally conducted for a business, a corporation, or even a political campaign. It typically addresses some real-life problem or need. Public research usually takes place in academic and government settings. It tries to clarify, explain, or predict—in other words, to theorize about—the effects of mass media rather than to address a consumer problem.

Most media research today focuses on media’s impact on human characteristics such as learning, attitudes, aggression, and voting habits. This research employs the scientific method, which consists of seven steps:

- Identify the problem to be researched.

- Review existing research and theories related to the problem.

- Develop working hypotheses or predictions about what the study might find.

- Determine an appropriate method or research design.

- 5. Collect information or relevant data.

- Analyze results to see whether they verify the hypotheses.

- Interpret the implications of the study.

The scientific method relies on objectivity (eliminating bias and judgments on the part of researchers), reliability (getting the same answers or outcomes from a study or measure during repeated testing), and validity (demonstrating that a study actually measures what it claims to measure).

A key step in using the scientific method is posing one or more hypotheses: tentative general statements that predict the influence of an independent variable on a dependent variable, or relationships between variables. For example, a researcher might hypothesize that frequent TV viewing among adolescents (independent variable) causes poor academic performance (dependent variable). Or, a researcher might hypothesize that playing first-person-shooter video games (independent variable) is associated with aggression in children (dependent variable).

Researchers using the scientific method may employ experiments or survey research in their investigations.

Experiments

Like all studies that use the scientific method, experiments in media research isolate some aspect of content; suggest a hypothesis; and manipulate variables to discover a particular medium’s impact on people’s attitudes, emotions, or behavior. To test whether a hypothesis is true, researchers expose an experimental group—the group under study—to selected media images or messages. To ensure valid results, researchers also use a control group that is not exposed to the selected media content and thus serves as a basis for comparison. Subjects are picked for each group through random assignment, meaning that each subject has an equal chance of being placed in either group.

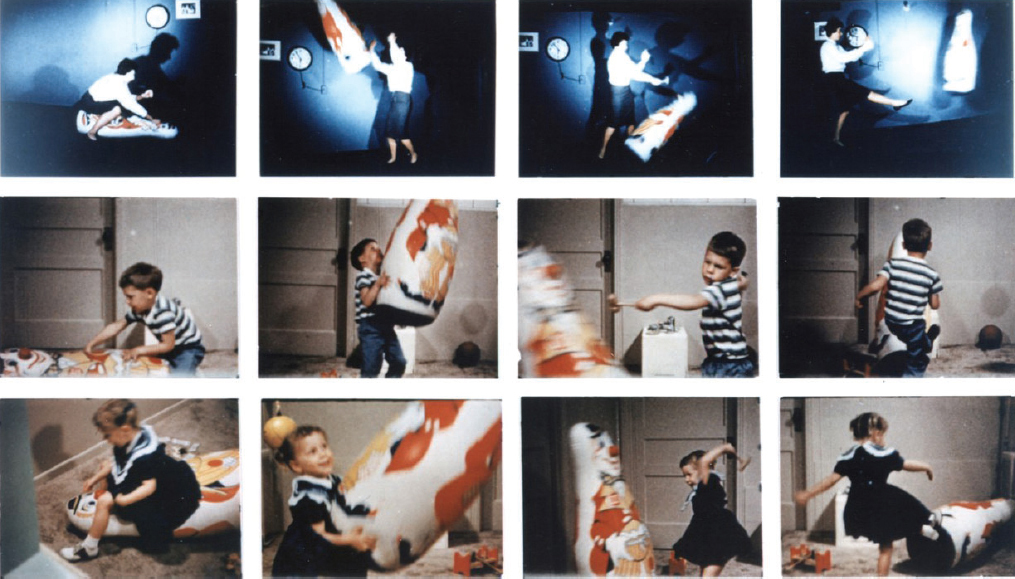

For instance, suppose researchers wanted to test the effects of violent films on preadolescent boys. The study might take a group of ten-year-olds and randomly assign them to two groups. The experimental group watches a violent action movie that the control group does not see. Later, both groups are exposed to a staged fight between two other boys, and researchers watch how each group responds. If the control subjects try to break up the fight but the experimental subjects do not, researchers might conclude that the violent film caused the differences in the groups’ responses. (See the Bobo doll” experiment photos below.)

When experiments carefully account for independent variables through random assignment, they generally work well to substantiate cause-effect hypotheses. Although experiments can sometimes take place in field settings, where people can be observed using media in their everyday environments, researchers have less control over variables. Conversely, a weakness of more carefully controlled experiments is that they are often conducted in the unnatural conditions of a laboratory environment, which can affect the behavior of the experimental subjects.

Survey Research

Through survey research, investigators collect and measure data taken from a group of respondents regarding their attitudes, knowledge, or behavior. Using random sampling techniques that give each potential subject an equal chance to be included in the survey, this research method draws on much larger populations than those used in experimental studies. Researchers can conduct surveys through direct mail, personal interviews, telephone calls, e-mail, and Web sites, thus accumulating large quantities of information from diverse cross sections of people. These data enable researchers to examine demographic factors in addition to responses to questions related to the survey topic.

Surveys offer other benefits as well. Because the randomized sample size is large, researchers can usually generalize their findings to the larger society as well as investigate populations over a long time period. In addition, they can use the extensive government and academic survey databases now widely available to conduct longitudinal studies, where they compare new studies with those conducted years earlier.

But like experiments, surveys also have several drawbacks. First, they cannot show cause-effect relationships. They can only show correlations—or associations—between two variables. For example, a random survey of ten-year-old boys that asks about their behavior might demonstrate that a correlation exists between acting aggressively and watching violent TV programs. But this correlation does not identify the cause and the effect. (Perhaps people who are already aggressive choose to watch violent TV programs.) Second, surveys are only as good as the wording of their questions and the answer choices they present. Thus, a poorly designed survey can produce misleading results.

Content Analysis

As social scientific media researchers developed theories about the mass media, it became increasingly important to more precisely describe the media content being studied. As a corrective, they developed a method known as content analysis to systematically describe various types of media content.

Content analysis involves defining terms and developing a coding scheme so that whatever is being studied—acts of violence in movies, representations of women in television commercials, the treatment of political candidates in news reports—can be accurately judged and counted. One annual content analysis study is conducted by the Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation (GLAAD) each year to count the quantity, quality, and diversity of gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender (GLBT) characters on television. In 2011, GLAAD’s content analysis found that ABC Family led all networks with 55 percent of its programming hours featuring GLBT characters. TBS and A&E were at the bottom of their list, each with just 5 percent of its programming time featuring GLBT characters.

Content analysis has its own limitations. For one thing, this technique does not measure the effects of various media messages on audiences or explain how those messages are presented. Moreover, problems of definition arise. For instance, how do researchers distinguish slapstick cartoon aggression from the violent murders or rapes shown during an evening police drama?