The Printing Press and the Publishing Industry: Books Become a Mass Medium

Printed Page 38

Books moved from the entrepreneurial stage to mass medium status with the invention of the printing press (which made books widely available for the first time) and the rise of the publishing industry (which arose to satisfy people’s growing hunger for books).

The Printing Press

The printing press was invented by Johannes Gutenberg in Germany between 1453 and 1456. Drawing on the principles of movable type, and adapting a device from the design of a wine press, Gutenberg’s staff of printers produced the first so-called modern books, including two hundred copies of a Latin Bible—twenty-one of which still exist. The Gutenberg Bible (as it’s now known) was printed on a fine calfskin-based parchment called vellum.

Printing presses spread rapidly across Europe in the late 1400s and early 1500s. Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales was the first English work to be printed in book form. Many of these early books were large, elaborate, and expensive. But printers gradually reduced books’ sizes and developed less-expensive grades of paper. These changes made books cheaper to produce, so printers could sell them for less, making the books affordable to many more people.

The spread of printing presses and books sparked a major change in the way people learned. Previously, people followed the traditions and ideas framed by local authorities—the ruling class, clergy, and community leaders. But as books became more broadly available, people gained access to knowledge and viewpoints far beyond their immediate surroundings and familiar authorities. Some of them began challenging the traditional wisdom and customs of their tribes and leaders.2 This interest in debating ideas would ultimately encourage the rise of democratic societies in which all citizens had a voice.

The Publishing Industry

In the two centuries after the invention of the printing press, publishing—the establishment of printing shops to serve the public’s growing demand for books—took off in Europe, eventually spreading to England and finally to the American colonies. In colonial America, English locksmith Stephen Daye set up a print shop in the late 1630s in Cambridge, Massachusetts. There, he and his son printed The Whole Booke of Psalms (known today as The Bay Psalm Book), marking the beginning of book publishing in the colonies. By the mid-1760s, all thirteen colonies had printing shops. Some publishers (such as Benjamin Franklin, who published several popular novels by British author Samuel Richardson) grew quite wealthy in this profession.

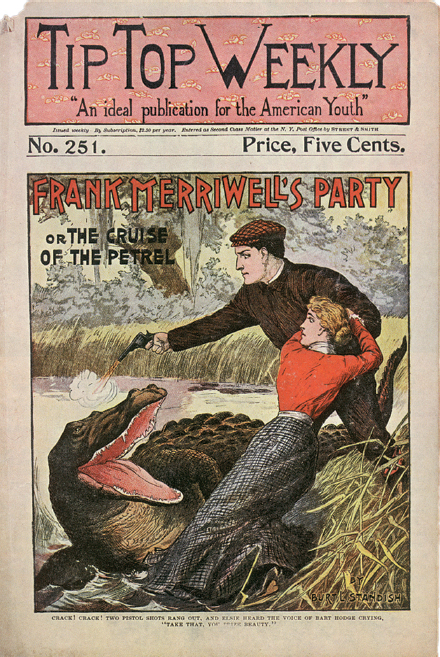

However, in the early 1800s, U.S. publishers had to find ways to lower the cost of producing books to meet exploding demand. By the 1830s, machine-made paper replaced the more expensive handmade varieties, cloth covers supplanted costlier leather ones, and paperback books with cheaper paper covers (introduced from Europe) all helped to make books even more accessible to the masses. Further reducing the cost of books, publishers Erastus and Irwin Beadle introduced paperback dime novels (so called because they sold for five or ten cents) in 1860. By 1885, one-third of all books published in the United States consisted of popular paperbacks and dime novels, sometimes identified as pulp fiction (a reference to the cheap, machine-made pulp paper they were printed on).

Meanwhile, the printing process itself also advanced. In the 1880s, the introduction of linotype machines enabled printers to save time by setting type mechanically using a typewriter-style keyboard. The introduction of steam-powered and high-speed rotary presses also permitted the production of even more books at lower costs. In the early 1900s, with the development of offset lithography, publishers could print books from photographic plates rather than from metal casts. This greatly reduced the cost of color ink and illustrations and accelerated the production process—enabling publishers to satisfy Americans’ steadily increasing demand for books.