Early Regulation of Wireless/Radio

Printed Page 166

By the turn of the twentieth century, radio had become a new force in American life. U.S. lawmakers—recognizing radio’s power to shape political opinion, economic dynamics, and military strategy and tactics—moved to ensure U.S. control over the fledgling industry. With this goal in mind, legislators first defined radio as a shared resource for the public good. Then they passed laws regulating how the public airwaves could be used and in what manner private businesses could take part in the industry.

Providing Public Safety

Because radio waves crossed state and national borders, legislators determined that broadcasting constituted a “natural resource”—a kind of interstate commerce. Therefore, radio waves could not be owned; they were the collective property of all Americans, just like national parks. And as collective property, they should provide a benefit to society. To that end, U.S. lawmakers enacted rules focused on national security and public safety, but which also set the stage for the emergence of radio as a public mass medium.

The first came in 1910, when Congress passed the Wireless Ship Act. The law mandated that all major U.S. seagoing ships carrying more than fifty passengers and traveling more than two hundred miles off either coast be equipped with wireless equipment with a one-hundred-mile range. The importance of this act was underscored by the Titanic disaster in 1912, when radio distress signals called rescue ships, enabling them to save more than seven hundred lives. In the wake of the Titanic tragedy, Congress passed the Radio Act of 1912, which required all radio stations on land or at sea to be licensed and assigned special call letters, and for each station to be operated only by a licensed person. The act helped to bring some order to the airwaves, which had been increasingly jammed with amateur radio operators. This act also formally adopted the SOS Morse-code distress signal that other countries had been using for several years.

Ensuring National Security

The government also took steps to ensure that radio contributed to national security. By 1915, more than twenty American companies sold wireless point-to-point communication systems, primarily for use in ship-to-shore communication. American Marconi (a subsidiary of British Marconi) was the biggest of these companies. But in 1914, with World War I erupting in Europe, the U.S. Navy questioned the wisdom of allowing a foreign-controlled company to wield so much power over communication. When the United States entered the war in 1917, the government closed down all amateur radio operations, took control of key radio transmitters, and blocked British Marconi from purchasing alternators from General Electric. These moves addressed concerns about national security. They also enabled the United States to reduce Britain’s influence over communication and tightened U.S. control over the emerging wireless infrastructure—key steps in safeguarding U.S. interests.

RCA: The Formation of an American Radio Monopoly

Some members of Congress, along with some business leaders, opposed federal legislation granting the government or the navy a radio monopoly. To secure a place in the fast-evolving industry, General Electric proposed a plan by which it would create a private-sector-monopoly—a privately owned company that would have the government’s approval to dominate the radio industry. In 1919, the plan was accepted by the powers that be at both General Electric and the U.S. Navy, the government branch most prominently fighting for control of the radio industry in America. GE swiftly broke off negotiations to sell key radio technologies to European-owned companies such as British Marconi, thereby limiting those companies’ global reach. In 1919, it founded a new company, Radio Corporation of America (RCA), which soon acquired American Marconi as well as radio patents of other U.S. companies and wireless patents from AT&T. Having pooled the necessary technology and patents to monopolize the wireless industry, RCA was poised to expand American communication technology throughout the world.3

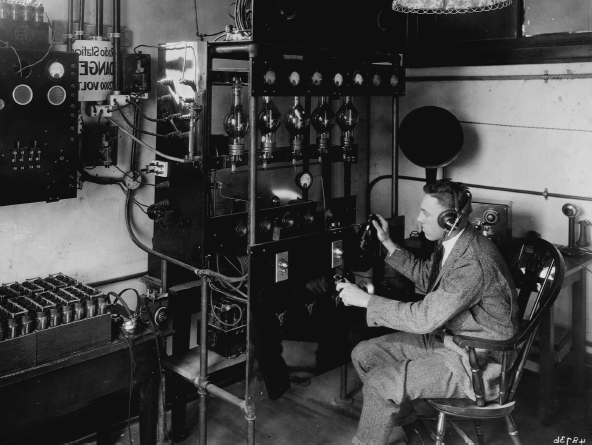

KDKA: The First Commercial Radio Station

With the advent of the United States’ global dominance in mass communication, many people became intrigued by radio’s potential. Amateur stations popped up in places like San Jose, California; Medford, Massachusetts; New York; Detroit; and Pierre, South Dakota. The best-known early station was started by an engineer named Frank Conrad, who worked for GE’s rival, Westinghouse Electric Company. In 1916, he set up a radio studio above his Pittsburgh garage by placing a microphone in front of a phonograph. Conrad broadcast music and news to his friends (whom he supplied with receivers) two evenings a week on experimental station 8XK. When a Westinghouse executive got wind of Conrad’s activities in 1920, he established KDKA, generally regarded as the first commercial (profit-based) broadcast station. The following year, the U.S. Commerce Department officially licensed five radio stations for operation; by early 1923, more than six hundred commercial and noncommercial stations were operating. Just two years later, a whopping 5.5 million radio sets were in use across America—made by companies such as GE and Westinghouse and costing about $55 ($664 in today’s dollars). Radio was officially a mass medium.