The Networks

Printed Page 169

With the establishment of the private sector’s involvement in radio, the groundwork was laid for radio to take off as a business—which would enable commercial station owners (and the advertisers that funded them) to reach more listeners more efficiently than ever. The radio network arose: a cost-saving operation that links a group of affiliate or subsidiary broadcast stations that share programming produced at a central location. (At that time, stations were linked through special phone lines; today, it’s through satellite relays.)

A network enables stations to control program costs and avoid unnecessary duplication of content creation. Simply put, it was cheaper to produce programs at one station and broadcast them simultaneously over multiple owned or affiliated stations than for each station to generate its own programs. Networks thus brought the best musical, dramatic, and comedic talent to one place, where programs could be produced and then distributed all over the country. This new business model concentrated control of radio in the hands of a few corporate players, all of whom jockeyed for additional power.

AT&T: Making a Power Grab

The shift toward networks began in 1922 when RCA’s partnership with AT&T started to unravel. In a major power grab, AT&T, which already had a government-sanctioned monopoly in the telephone business, decided to break its RCA agreements in an attempt to monopolize radio. Identifying the new medium as the “wireless telephone,” AT&T argued that broadcasting was merely an extension of its control over the telephone. The corporate giant complained that RCA had gained too much power. In violation of its early agreements with RCA, AT&T began making and selling its own radio receivers.

That same year, AT&T started WEAF (now WNBC) in New York, the first radio station to regularly sell commercial time to advertisers. Advertising (company executives reasoned) would ensure profits long after radio-set sales had saturated the consumer market. AT&T claimed that under the RCA agreements, it had the exclusive right to sell ads, which AT&T called toll broadcasting. Most people in radio at the time recoiled at the idea of using the medium for advertising, viewing the medium instead as a public information service. But executives remained riveted by the potential of radio ads to enhance profits.

Still, the initial motivation behind AT&T’s toll broadcasting idea was to dominate radio. Through its agreements with RCA, AT&T retained the rights to interconnect the signals between two or more radio stations via telephone wires. By the end of 1924, AT&T had interconnected twenty-two stations in a network to air a talk by President Calvin Coolidge. Some of these stations were owned by AT&T, but most simply consented to become AT&T “affiliates,” agreeing to air the phone company’s programs.

Seeing AT&T’s success, GE, Westinghouse, and RCA launched a competing network. AT&T promptly denied them access to its telephone wires, so GE, Westinghouse, and RCA used inferior telegraph lines to connect its network stations. In 1925, the Justice Department, irritated by AT&T’s power grab, redefined patent agreements. AT&T received a monopoly on providing the wires, known as long lines, to interconnect stations nationwide. In exchange, AT&T agreed to sell its network to RCA for $1 million and promised not to reenter broadcasting for eight years.

NBC: RCA Forms a Network

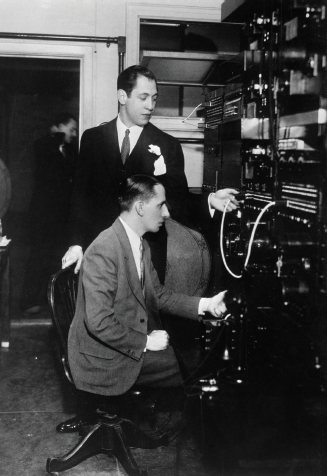

The commercial rewards of the network and affiliate system continued to excite executives’ imaginations. For example, after RCA bought AT&T’s telephone network, David Sarnoff, RCA’s general manager, created a new subsidiary in September 1926 called the National Broadcasting Company (NBC). NBC’s ownership was shared by RCA (50 percent), General Electric (30 percent), and Westinghouse (20 percent). The subsidiary became known as the NBC-Red network. The network created by RCA, GE, and Westinghouse became a sister network named NBC-Blue. By 1933, NBC-Red would have twenty-eight affiliates; NBC-Blue, twenty-four.

CBS: A Rival Network Challenges NBC

The network and affiliate system under RCA/NBC thrived throughout most of the 1920s and brought Americans together as never before to participate in the big events of the day. For example, when aviator Charles Lindbergh returned from the first solo transatlantic flight in 1927, an estimated twenty-five to thirty million people listened to his welcome-home party on the six million radio sets then in use. At the time, it was the largest shared audience experience in the history of any mass medium.

During this decade, competition also stiffened further within the industry. For instance, in 1928, William Paley, the twenty-seven-year-old son of a Philadelphia cigar company owner, bought the Columbia Phonograph Company and built it into a network later renamed the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS). Unlike NBC, which actually charged its affiliates up to $96 a week for having the privilege of carrying its programming, CBS paid affiliates as much as $50 an hour to carry its programs. By 1933, Paley’s efforts had netted CBS more than ninety affiliates, many of which had defected from NBC. Paley also concentrated on developing news programs and entertainment shows, particularly soap operas and comedy-variety series. To that end, CBS raided NBC not just for affiliates but for top talent such as comedian Jack Benny and singer Frank Sinatra. In 1949, CBS finally surpassed NBC as the highest-rated network on radio.