Staining TV’s Reputation

Printed Page 231

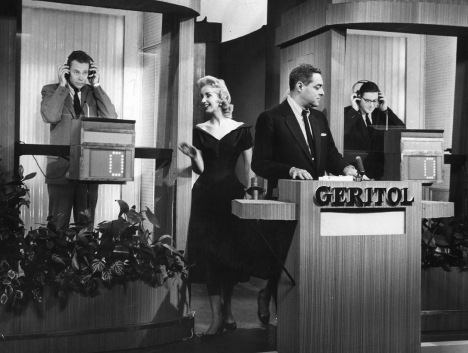

In the late 1950s, corruption in an increasingly popular TV program format—quiz shows—tainted TV’s reputation and further altered the power balance between broadcast networks and program sponsors. Quiz shows had become huge business. By the end of the 1957–58 TV season, twenty-two of them aired on network television. They were (and remain) cheap to produce, with inexpensive sets and amateurs as guests. For each show the corporate sponsor—like Revlon or Geritol—prominently displayed its name on the set throughout the program.

But as it turned out, many quiz shows were rigged. To heighten the drama and get rid of unappealing guests, sponsors pressured TV executives to give their favorite contestants answers to the quiz questions and allow them to rehearse their responses. The most notorious rigging occurred on Twenty-One, a quiz show owned by Geritol, whose profits had climbed by a whopping $4 million a year after it began sponsoring the program in 1956.

When investigations exposed the rigging, the networks further decreased their use of sponsors to create programming. Even more important, the fraud undermined Americans’ belief in TV’s democratic promise—to bring inexpensive, honest information and entertainment into every household. The scandals had magnified the separation between the privileged, powerful few (wealthy companies) and the general public. For the next forty years, the broadcast networks kept quiz shows out of prime time—the block of time (7–11 P.M. EST) with large viewer audiences.