Money In and Money Out

Printed Page 276

The Internet’s quick commercialization in the 1990s led to battles between corporations vying to attract the most users. In the beginning, commercial entities like AOL (America Online) and Microsoft sought to capture business as Internet service providers and Web browsing software companies, respectively. What no one anticipated was the emergence of search engines as a key advertising force, and the influence a small Internet start-up—Google—would have over Internet content within less than a decade. The main commercial services of the Web fall into four areas: Internet service providers, Web browsers, and directories and search engines.

Internet Service Providers

Since the early 1990s, Internet service providers (ISPs) have competed to provide consumers with access to the Internet. The earliest ISPs offered dial-up access. Today, the preferred access method is through broadband connections—which can quickly download multimedia content via high-speed service from cable, telephone, or satellite companies—making those companies the top ISPs.

AOL initially tried to dominate the ISP industry, connecting millions of home users to its proprietary Web system through dial-up access. The company was so successful that media giant Time Warner merged with AOL in 2000. However, AOL’s dial-up ISP business sharply declined as its customers shifted to broadband. The company adapted to the broadband environment by dropping its monthly membership service charge, making its content free, and attempting to capture more customers and thus attract more advertisers. Today, AOL’s sites—including AOL Instant Messenger, ICQ, CitySearch, Moviefone, and MapQuest—are among the most visited properties on the Internet, but AOL itself is a much smaller company. Time Warner finally split from AOL in 2009, as the promise of controlling the Internet through the merger nine years earlier never materialized. AOL worked to reinvent itself as a content company with the acquisition of Patch.com and community news sites in 2009, and the purchase of the Huffington Post in 2011.

Web Browsers

In the early 1990s, as the Web became the most popular part of the Internet, companies like Microsoft thought that the key to commercial success on the Net would be through a Web browser, since it is the most common interface with the Internet.

Beginning in 1995, Microsoft, at that time with a near-monopoly over computer operating systems with its Windows software, built a near-monopoly over the Internet by strategically bundling its Windows 95 operating system with its new Internet Explorer browser software. The release of Windows 95, which made Internet Explorer the preferred browser for computers using Windows, devastated Netscape, the most popular browser at the time. Alarmed by the company’s growing power, the U.S. Department of Justice brought an antitrust lawsuit against Microsoft in 1997, arguing that it had used its operating-system dominance to sabotage competing browsers. In 2001, the Department of Justice dropped its efforts to break Microsoft into two independent companies. In Europe, though, the European Union ruled that Microsoft committed antitrust violations and fined Microsoft a total of about $2.5 billion.3 Web browsers never became huge revenue-generating portals, and today companies like Microsoft, Apple, and Google release free browsers as a way to familiarize users with their other software. (Firefox, a nonprofit open-source browser, is an exception.) Although Internet Explorer continues to be the dominant Web browser, there is increasing competition from Firefox, Google Chrome, Safari, and Opera.

Directories and Search Engines

As Web sites rapidly proliferated on the Internet throughout the early 1990s, entrepreneurs seized the opportunity to help users navigate this vast amount of information. Two types of companies emerged—directories and search engines.

Directories rely on people to review and catalogue Web sites, creating categories with hierarchical topic listings that can be browsed. Yahoo! was one of the first companies to successfully provide such a service. Established in 1994, Yahoo!’s directory quickly dominated the Web-directory market by acting as an all-purpose entry point, or portal, to the Internet.

Search engines offer a different route for finding content on the Web: a complicated algorithm and an enormous database of Web pages compiled and regularly updated by the search-engine company. Users type in key words, and the algorithm is then applied to the company’s massive database, gleaning a list of Web pages ranked in order of relevance. Beyond its directory, Yahoo! began syndicating with the search-engine service Inktomi to bring algorithmic search to its very popular portal.

In 1998, Google introduced the first algorithm to mathematically rank a page’s “popularity” based on how many other pages link to it—and immediately became the megastar search engine. Even Yahoo! switched to Google, along with many other portals, as its main search provider. However, search-engine syndication provided only so much revenue. The application that made search engines (and Google especially) such important Web properties in the early 2000s was the ability to connect advertisers to the same key words users were typing into the search box. Ad sites soon appeared alongside (and in some cases, within) an algorithmic search list—an advertising strategy that was far more effective than banner ads. Google transformed almost overnight from a syndicated search-engine service into an advertising firm. Yahoo! and Microsoft have heavily invested in competing search-engine initiatives to reap some of the advertising profits but have not been able to match Google’s superior search engine. By 2011, Google had more than 65 percent of the search-engine market in the United States, while Yahoo!’s share was about 15 percent. Microsoft’s share had hit about 15 percent, just behind Yahoo!, with their Bing search engine.

Today, Google generates billions of dollars of revenue each year through the pay-per-click advertisements that accompany key-word searches. (Each time a user clicks on an online ad, Google gets money.) The company now also offers other Internet services, including shopping (Froogle), mapping (Google Maps), e-mail (Gmail), blogging (Blogger), and browsing (Chrome), and has begun to experiment with behavioral advertising and the placement of TV ads. Google has even begun challenging Microsoft’s Office programs with Google Apps software. In its most significant investments to date, Google acquired YouTube for $1.64 billion and purchased DoubleClick, one of the Internet’s leading advertising placement companies.

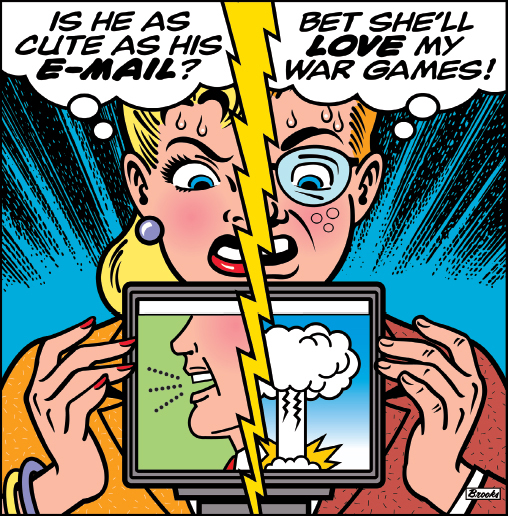

Because sending and receiving e-mail is still one of the most popular uses of the Internet, major Web corporations such as Yahoo!, AOL, Google, and Microsoft continue to offer free e-mail accounts to draw users to their sites; even Facebook introduced e-mail accounts in 2010. Each of these companies, some with millions of users, generates revenue through advertisements in subscribers’ e-mail messages, with Google’s Gmail ads tailored to keywords contained in the message.

A Closer Look at Advertising on the Internet

As previously noted, in the early years of the Web, advertising consisted of traditional display ads placed on pages. These reached small, general audiences and thus weren’t very profitable. In the late 1990s, Web advertising began shifting to search engines. Paid links appeared as “sponsored links” at the top, bottom, and side of a search-engine result list. Every time a user clicks on a sponsored link, the advertiser pays the search engine for the click-through. However, even though search engines insist on the relevance of their search results, the increasingly commercial nature of the Web and ability of commercial sites to buy advertisements on popular sites (thus making more links) means that search-engine results are biased toward commercial sites.

Advertising has also spread from Web pages to the newer, more interactive elements of the Internet, including social networking sites in which computer users reveal something about themselves and their interests. This information has made Internet advertising the most targeted kind of advertising in the history of mass communication. For example, Yahoo! gleans information from the search terms, Google scans the contents of Gmail messages, for keywords and Facebook uses profile information (age, gender, location, interests) to deliver individualized ads to users’ screens.

Overhead: Building the Infrastructure

We’ve just explored ways in which companies make money by attracting users—and thus advertisers—to the Internet. But what about money they have to spend to build their Internet businesses? “Money out” takes the form of investments in infrastructure needed for the Internet to operate. This infrastructure includes software, facilities, and equipment such as fiber-optic networks and bandwidth.