Military Functions, Civic Roots

Printed Page 266

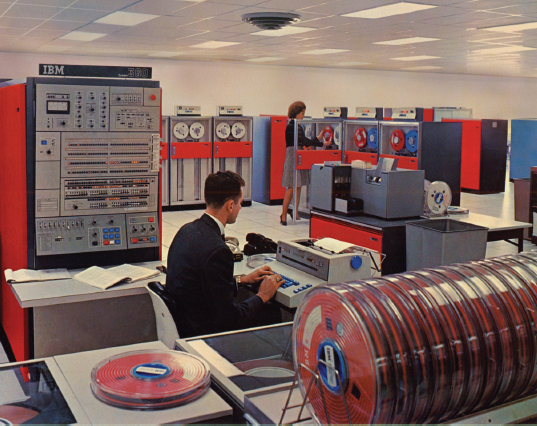

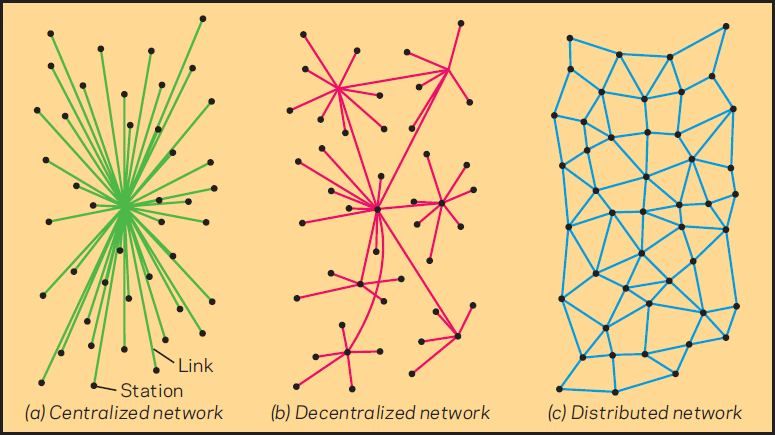

Created in 1958, the U.S. Defense Department’s Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) assembled a team of computer scientists around the country to develop and test technological innovations. Computers were relatively new at this time, and there were only a few expensive mainframe computers, each big enough to fill an entire room. Yet, the scientists working on ARPA projects wanted access to these computers. A solution to the problem was proposed: First, share computer processing time by creating a wired network system in which users from multiple locations could log onto a computer whenever they needed it. Second, to prevent logjams in data communication, the network used a system called packet switching, which broke down messages into smaller pieces to easily route through the network, and reassembled them on the other end. This system provided multiple paths linking computers to one another, thereby allowing communication to continue if one of the paths got clogged or disrupted—much like the national highway system supported by President Eisenhower. This computer network became the original Internet—called ARPAnet and nicknamed the Net—and it enabled military and academic researchers to communicate on a distributed network system (see Figure 9.1).

With only a few large, powerful research computers in the country, many computer scientists were suddenly able to access massive (for that time) amounts of computer power. The first Net messages ever were sent in 1969, when ARPAnet connections linked four universities: the University of California–Los Angeles, the University of California–Santa Barbara, Stanford, and the University of Utah. By 1970, another terminal was in place in Cambridge, Massachusetts, at computer research firm Bolt, Beranek and Newman (BBN), and by late 1971 there were twenty-three Internet hosts at university and government research centers across the United States. This same year, Ray Tomlinson of BBN came up with an essential innovation to help researchers communicate—e-mail—and decided to use the “@” sign to separate the user’s name from the computer name, a convention that has been used ever since.

During this development stage, the Internet (still called ARPAnet at this time) was used primarily by universities, government research labs, and corporations involved in computer software and other high-tech products. These users exchanged e-mail and posted information on computer bulletin boards, sites that listed information about particular topics such as health, technology, or employment services.