The Evolution of Digital Gaming

In their most basic form, digital games involve users in an interactive computerized environment where they strive to achieve a desired outcome. These days, most digital games go beyond a simple competition like Pong; they often entail sweeping narratives and offer imaginative and exciting adventures, sophisticated problem-solving opportunities, and multiple possible outcomes.

But the boundaries were not always so varied. Digital games evolved from their simplest forms in the arcade into four major formats: television, handheld devices, computers, and finally the Internet. As these formats evolved and graphics advanced, distinctive types of games emerged and became popular. These included classically structured games played in arcades and on consoles and mobile devices, online role-playing games, computerized versions of card games, fantasy sports leagues, and virtual social environments. Together, these varied formats constitute an industry that now generates more than $45 billion in annual revenues worldwide—and that has become a socially driven mass medium.

Arcades and Classic Games

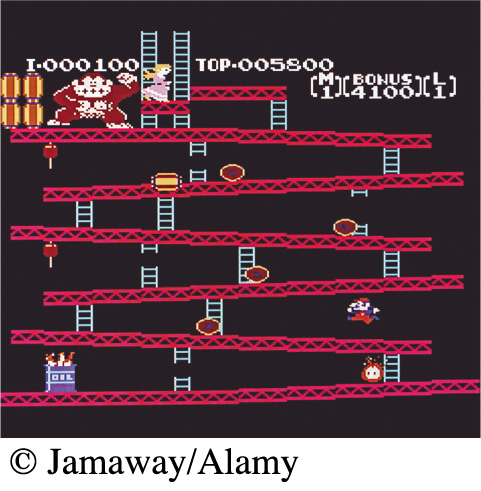

By the late 1970s and early 1980s, games like Asteroids, Pac-Man, and Donkey Kong filled arcades and bars, competing with traditional pinball machines. In a way, arcades signaled digital gaming’s potential as a social medium, because many games allowed players to compete with or against each other, standing side by side. To be sure, arcade gaming has been superseded by the console and computer. But the industry still attracts fun-seekers to amusement parks, malls, and casinos, as well as to businesses like Dave & Buster’s—a gaming/restaurant chain operating in more than fifty locations.

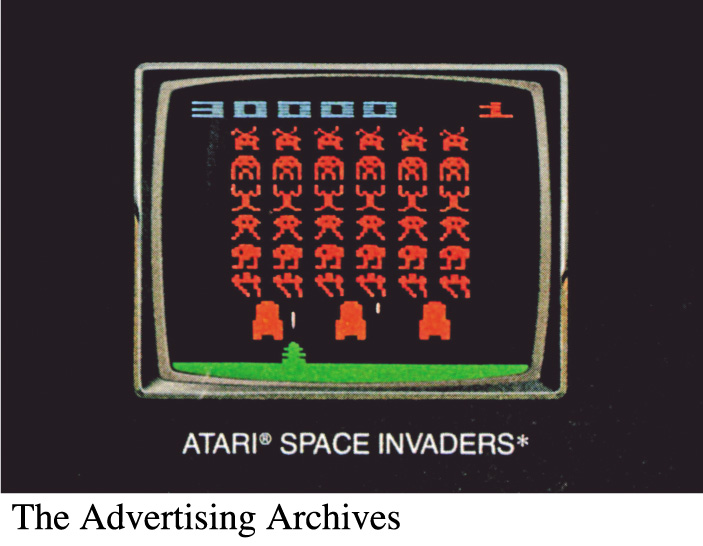

To play the classic arcade games, as well as many of today’s popular console games, players use controllers like joysticks and buttons to interact with graphical elements on a video screen. With a few notable exceptions (puzzle games like Tetris, for instance), these types of video games require players to identify with a position on the screen. In Pong, this position is represented by an electronic paddle; in Space Invaders, it’s an earthbound shooting position. After Pac-Man, the avatar (a graphic interactive “character” situated within the world of the game) became the most common figure of player control and position identification. In the United States, the most popular video games today assume a first-person perspective, in which the player “sees” the virtual environment through the eyes of an avatar. In contrast, players in South Korea often favor real-time strategy games with an elevated three-quarters perspective, which affords a grander and more strategic vantage point on the field of play.

Consoles and Advancing Graphics

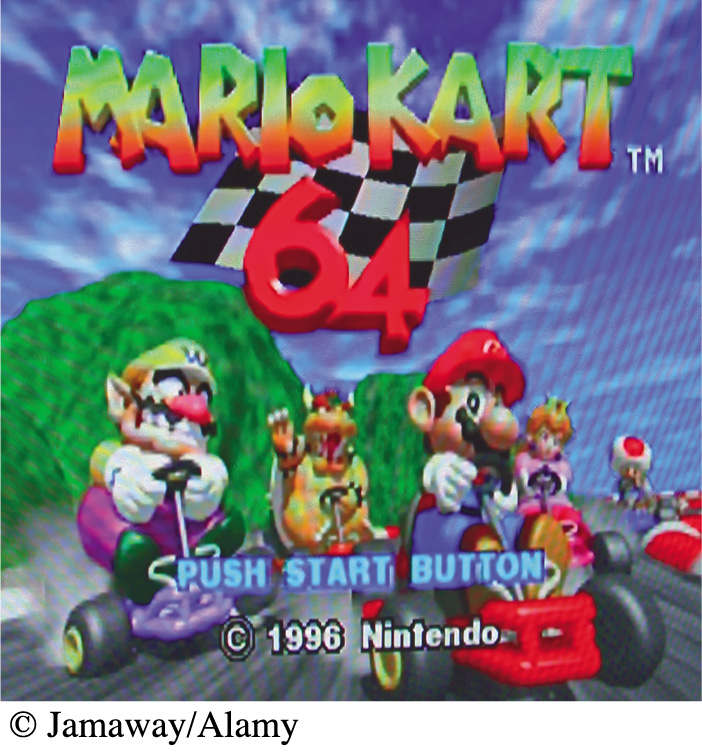

Today, many digital games are played on home consoles, devices people use specifically to play video games. These systems have become increasingly more powerful since the appearance of the early Atari consoles in the 1970s. One way of charting the evolution of consoles is to track the number of bits (binary digits) they can process at one time. The bit rating of a console is a measure of its power at rendering computer graphics. The higher the bit rating, the more detailed and sophisticated the graphics. The Atari 2600, released in 1977, used an 8-bit processor, as did the wildly popular Nintendo Entertainment System, first released in Japan in 1983. Sega Genesis, the first 16-bit console, appeared in 1989. In 1992, 32-bit computers appeared on the market; the following year, 64 bits became the new standard. The 128-bit era dawned with the marketing of Sega Dreamcast in 1999. With the current generation of consoles, 256-bit processors are the standard.

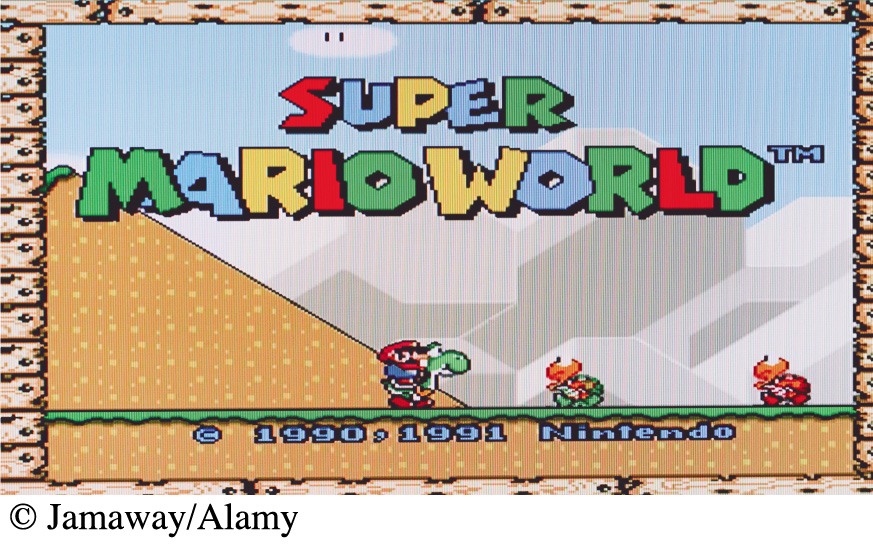

But more detailed graphics have not always replaced simpler games. Nintendo, for example, offers many of its older, classic games for download onto its newest consoles even as updated versions are released, for nostalgic gamers as well as new fans. Perhaps the best example of enduring games is the Super Mario Bros. series. Created by Nintendo mainstay Shigeru Miyamoto in 1983, the original Mario Bros. game began in arcades. The 1985 sequel—Super Mario Bros., developed for the 8-bit Nintendo Entertainment System—became the best-selling video game of all time. It held this title until as recently as 2009, when it was unseated by Nintendo’s Wii Sports. Graphical elements from the Mario Bros. games, like the “1-Up” mushroom that gives players an extra life, remain instantly recognizable to gamers of all ages. Some even appear on nostalgic T-shirts, as toys and cartoons, and in updated versions of newer games.

Through decades of ups and downs in the digital gaming industry (Atari closing down, Sega no longer making video consoles), three major home console makers emerged: Nintendo, Sony, and Microsoft. Nintendo has been making consoles since the 1980s; Sony and Microsoft came later, but both companies were already major media conglomerates and thus well positioned to support and promote their interests in the video game market. Veteran digital manufacturer Sony has the second most popular console, its PlayStation series, introduced in 1994. Its current console, the PlayStation 4 (PS4), boasts more than one hundred million users on its online PlayStation Network. Microsoft’s first foray into video game consoles was the Xbox, released in 2001 and linked to the Xbox LIVE online service in 2002. Xbox LIVE allows its nearly fifty million subscribers to play online and enables users to download new content directly to the console—the Xbox One. In 2015, this was the world’s third most popular console.

Nintendo released its most recent console, the Wii, in 2006. The device supports traditional video games like the New Super Mario Bros. However, its unique wireless motion-sensing controller takes the often-sedentary nature out of video gameplay. Games like Wii Sports require the user to mimic the full-body motion of bowling or playing tennis, while Wii Fit uses a wireless balance board for interactive yoga, strength, aerobic, and balance games. Although the Wii has lagged behind Xbox and PlayStation in establishing an online community, it is now the best selling of the three major console systems.

Advances in graphics and gameplay have also enhanced smaller handheld consoles. Nintendo’s Game Boy, a two-color handheld console introduced in 1989, was one early success, selling far more than the competing Sega Game Gear and Atari Lynx, even though those two systems included full-color graphics. For many players, cutting-edge graphics on handheld consoles were—and remain—second in importance to convenience and simplicity. Nonetheless, the early handhelds gave way to later generations of devices, offering more advanced graphics and wireless capabilities. These include the Nintendo DS and the PlayStation PSP, as well as simpler games played on smartphones and other mobile devices. Handheld video games have made the medium more accessible and widespread. Even people who wouldn’t identify themselves as gamers may kill time between classes or waiting in line by playing Words with Friends on their phones.

Computers and Related Gaming Formats

Early home computer games, like the early console games, often mimicked (and sometimes ripped off) popular arcade games like Frogger, Centipede, Pac-Man, and Space Invaders. But for a time in the late 1980s and much of the 1990s, personal computers held some clear advantages over console gaming. The versatility of keyboards, compared with the relatively simple early console controllers, allowed for ambitious puzzle-solving games like Myst. Moreover, faster processing speeds gave some computer games richer, more detailed three-dimensional (3-D) graphics. Many of the most popular, early first-person shooter games (like Doom and Quake) were developed for home computers rather than traditional video game consoles. As consoles caught up with greater processing speeds and disc-based games in the late 1990s, elaborate computer games attracted less attention.

But computer-based gaming survives in the form of certain genres not often seen on consoles. Examples include the digitization of card and board games. In video games, players identify with a playing position on the screen; in digital versions of card and board games, players remain positioned outside the field of play.

The early days of the personal computer saw the creation of digital versions of Solitaire; digital versions of games like Hearts, Spades, and Chess followed. Currently, players can build their skills by playing against the computer and then test their skills by competing in online matches with other people. Sometimes players start online and then transfer their skills to traditional environments. For example, in 2003, Chris Moneymaker (his real name), an accountant from Tennessee, paid $39 to enter a qualifying tournament at PokerStars.com. He then moved from online poker to the face-to-face gaming tables of Las Vegas, where he ended up taking home the $2.5 million grand prize at the World Series of Poker. One of the largest and most vibrant types of digital gaming performs the reverse action, transferring real-world action into a gaming environment: online fantasy sports. Fantasy sports games eventually became a key component of Internet-connected social gaming.

The Internet and Social Gaming

With the introduction of the Sega Dreamcast in 1999, the first console to feature a built-in modem, game playing emerged as an online, multiplayer social activity. The Dreamcast didn’t last, but online connections are now a normal part of console video games. Internet-connected players oppose one another in combat, fight together against a common enemy, or team up to achieve a common goal (like sustain a medieval community). With multiple players joining in digital games via the Internet, this form of gaming has become a contemporary social medium.

Some of the biggest social gaming titles have been first-person shooter games like Counter-Strike, an online spin-off of the popular Half-Life console game. Each player views the game from the first-person perspective but also plays on a team, as either a terrorist or counterterrorist. The ability to play online has added a new dimension to other, less combat-oriented games, too. For example, football and music enthusiasts playing already-popular console games like Madden NFL and Rock Band can now engage with others in live, online, multiplayer play. And young and old alike can compete against teams in other locations in Internet-based bowling tournaments using the Wii.

The increasingly social nature of video games has made them a natural fit for social networking sites. Many online games—like Lexulous (inspired by the board game Scrabble) and Farmville—are now embedded in these sites. Online fantasy sports games also reach a mass audience with a major social component. Players—real-life friends, virtual acquaintances, or a mix of both—assemble teams and use actual sports results to determine scores in their online games. But rather than experiencing the visceral thrills of, say, Madden NFL 11, fantasy football participants take a more detached, managerial perspective on the game—a departure from the classic video game experience. Fantasy sports’ managerial angle makes it even more fun to watch almost any televised game. That’s because players focus more on making strategic investments in individual performances scattered across the various professional teams than they do in rooting for local teams. In the process, players become statistically savvy aficionados of the game overall, rather than rabid fans of a particular team. According to the Fantasy Sports Trade Association, in 2014, nearly forty-two million Americans and Canadians played fantasy sports, spending around three and a half billion dollars in the process.7

This kind of online community building has also enabled a fairly recent form of gaming: massively multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPGs). These games are set in virtual worlds that require users to play through an avatar of their own design. The fantasy adventure game World of Warcraft made a big splash when it launched just in time for the 2004 holiday season, growing steadily until membership peaked at around twelve million active subscribers globally in 2010, before those numbers dropped a bit to ten million by 2014.8 Users can select from ten different types of avatars, including dwarves, gnomes, night elves, orcs, trolls, and humans. To succeed in the game, many players join with other players to form guilds or tribes, working together toward in-game goals that can be achieved only through teams. Second Life, a 3-D social simulation set in real time, also features social interaction. Players build human avatars, selecting from an array of physical characteristics and clothing. They then use real money to buy virtual land and to trade in virtual goods and services.

Simulations like Second Life and MMORPGs like World of Warcraft are aimed at teenagers and adults. But one of the biggest areas in online gaming is the children’s market. Club Penguin, a moderated virtual world purchased by Disney, enables kids to play games and chat as colorful penguins. Similarly, the toy maker Ganz developed the online Webkinz World to revive its stuffed animal sales. Each Webkinz stuffed animal comes with a code that lets players access the online world, play games, and care for the virtual version of their plush pets.

Online games have further fostered media convergence. World of Warcraft, for instance, is now a comic-book series, a quarterly magazine, and a feature film in development with director Duncan Jones. The “massively multiplayer” aspect of MMORPGs also indicates that digital games—once designed for solo or small-group play—have expanded to reach large groups, similar to traditional mass media.

Consoles, Portables, and Entertainment Centers

In the earlier days of video games, their most prominent media crossovers came when a movie or perhaps a TV cartoon was derived from a popular game. Increasingly, though, games can be consumed the same way so much music, television, and film are consumed: just about anywhere, in a number of shapes, sizes, and styles. Video game consoles, once used exclusively for games, now work as part computer, part cable box. They’ve become powerful entertainment centers, with multiple forms of media converging in a single device. For example, Xbox 360 and PS3 can function as DVD players and digital video recorders (with hard drives of up to 250 gigabytes) and offer access to Twitter, Facebook, blogs, and video chat. PS3 can also play Blu-ray discs, and all three console systems offer connections to stream Netflix movies. Portable players like the top-selling Nintendo DS, released in 2004, and PlayStation Portable (PSP), released in 2005, are additional examples of converged gaming devices. Both are Wi-Fi capable, so players can interface with other DS or PSP users to play games or even browse the Internet.

Portable players remain immensely popular; Nintendo DS sold more than 154 million units through 2014. However, they face competition from the widespread use of smartphones and touchscreen tablets. These devices are not typically designed principally for games, but their capabilities bring casual gaming to customers who might not have been interested in the handheld consoles of the past. Manufacturers of these devices are catching on to their converged gaming potential: After years of relatively little interest in video games, Apple introduced Game Center in 2010. This social gaming network allows users to invite friends or find others for multiplayer gaming, track their scores, and view high scores on a leader board—which the DS and PSP do as well. With more than 500 million iPhones and more than 210 million iPads sold worldwide by 2014 (and millions more iPod Touch devices in circulation), plus more than 260,000 games like Blek and Minecraft: Pocket Edition available in its App Store, Apple has all the elements in place to transform the portable video game business.9 Gaming on smartphones will gather steam as well, especially with Xbox LIVE access on Microsoft’s Windows Phone 7.

| MAJOR VIDEO GAME CONVENTIONS | |||

| Innovation | Description | Examples | |

| Avatars | On-screen figures of player identification | Pac-Man, the Mario Bros. (right), Sonic the Hedgehog, Link from Legend of Zelda |

© Jamaway/Alamy

|

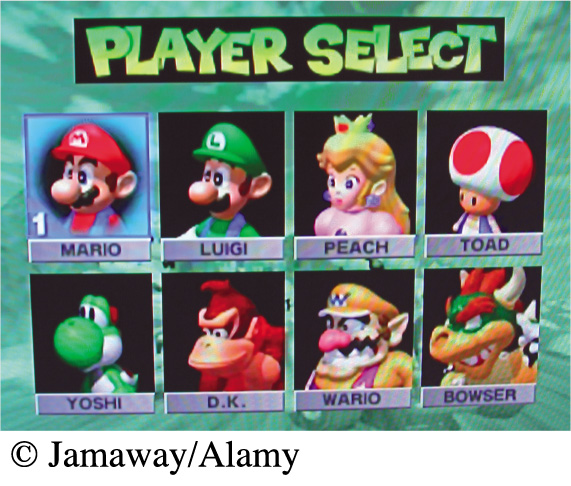

| Bosses | Powerful enemy characters that represent the final challenge in a stage or the entire game | Bowser from the Mario series, Hitler in Castle Wolfenstein, Donkey Kong (right) |

© Jamaway/Alamy

|

| Vertical and Side Scrolling | As opposed to a fixed screen, scrolling that follows the action as it moves up, down, or sideways in what is called a “tracking shot” in the cinema | Platform games like Jump Bug, Jungle King, and Super Mario Bros.; also integrated into the design of Angry Birds (right) |

© lifestyleUK/Alamy

|

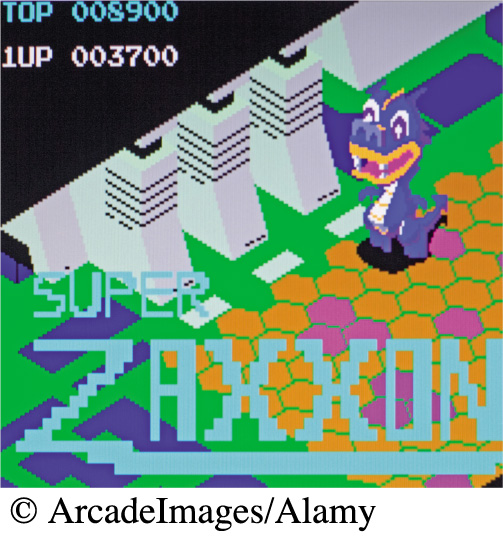

| Isometric Perspective (also called Three-Quarters Perspective) | An elevated and angled perspective that enhances the sense of three-dimensionality by allowing players to see the tops and sides of objects | Zaxxon (right), real-time strategy games like StarCraft, god games like Civilization and Populous |

© ArcadeImages/Alamy

|

| First-Person Perspective | Presents the gameplay through the eyes of your avatar | First-person shooter (FPS) games like Castle Wolfenstein, Doom (right), Halo, and Call of Duty |

Jonathan Alcorn/Bloomberg via Getty Images

|

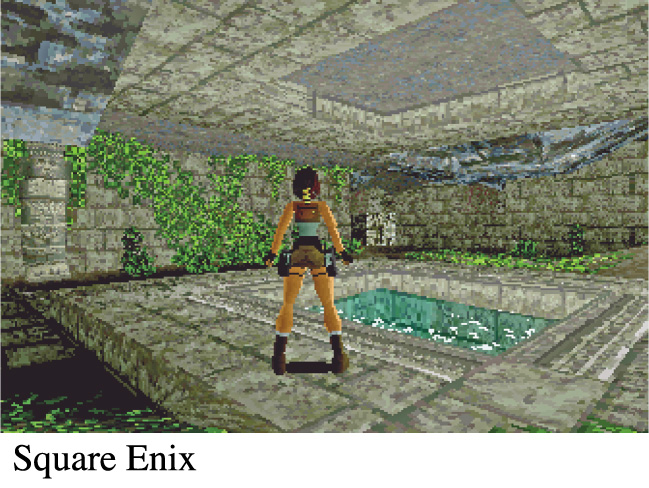

| Third-Person Perspective (or Over-the-Shoulders Perspective) | Enables you to view your heroic avatar in action from an external viewpoint | Tomb Raider (right), Assassin’s Creed, and the default viewpoint on World of Warcraft |

Square Enix

|

| Cut Scenes (also called In-Game Cinematic or In-Game Movie) | Narrative respite from gameplay, providing cinematic scenes that advance the story; often appear at the beginning of games and between levels | Well-known early example appears in Maniac Mansion (1987); cut scenes from games like the Grand Theft Auto series (right) have become increasingly vivid and complex |

The Advertising Archives

|

This convergence is changing the way people look at video games and their systems. The games themselves are no longer confined to arcades or home television sets, while the systems have gained power as entertainment tools, reaching a wider and more diverse audience. Many phones and PDAs operate as de facto handheld consoles, and many home consoles serve as comprehensive entertainment centers. Thus, gaming has become an everyday form of entertainment, rather than the niche pursuit of hard-core enthusiasts.

With its increased profile and flexibility across platforms, the gaming industry has achieved a mass medium status on par with that of film or television. This rise in status has come with stiffer and more complex competition, not just within the gaming industry but also across media. Rather than Sony competing with Nintendo, or TV networks competing among themselves for viewers, or new movies facing off at the box office, media must now compete against other media for an audience’s attention.