The Media Playground

To fully explore the larger media playground, we need to look beyond digital gaming’s technical aspects and consider the human faces of gaming. The attractions of this interactive playground validate digital gaming’s status as one of today’s most powerful social media. Players can interact socially within the games themselves; they can also participate in communities outside of the games, organized around gaming-related interests.

Communities of Play: Inside the Game

Virtual communities often crop up around online video games and fantasy sports leagues. Indeed, players may get to know one another through games without ever meeting in person. They can interact in two basic types of groups. PUGs (short for “Pick-Up Groups”) are temporary teams usually assembled by matchmaking programs integrated into the game. The members of a PUG may range from elite players to noobs (clueless beginners) and may be geographically and generationally diverse. PUGs are notorious for harboring ninjas and trolls—two universally despised player types (not to be confused with ninja or troll avatars). Ninjas are players who snatch loot out of turn and then leave the group; trolls are players who delight in intentionally spoiling the gaming experience for others.

Because of the frustration of dealing with noobs, ninjas, and trolls, most experienced players join organized groups called guilds or clans. These groups can be small and easygoing or large and demanding. Guild members can usually avoid PUGs and team up with guildmates to complete difficult challenges requiring coordinated group activity. As the terms ninja, troll, and noob suggest, online communication is often encoded in gamespeak—a language filled with jargon, abbreviations, and acronyms relevant to gameplay. The typical codes of text messaging (OMG, LOL, ROFL, and so forth) form the bedrock of this language system.

Players communicate in two forms of in-game chat—voice and text. Xbox LIVE, for example, uses three types of voice chat that allow players to socialize and strategize, either in groups or one-on-one. Other in-game chat systems, like that in World of Warcraft, are text-based, with chat channels for trading in-game goods or coordinating missions within a guild. These methods of communicating with fellow players who may or may not know one another outside the game create a sense of community around the game’s story. Some players have formed lasting friendships or romantic relationships through game playing. Avid gamers have even held in-game ceremonies, like weddings or funerals—sometimes for game-only characters, sometimes for real-life events.

Communities of Play: Outside the Game

Communities also form outside games, through Web sites and even face-to-face gatherings dedicated to digital gaming in its many forms. This is similar to when online and in-person groups form to discuss other mass media, such as movies, TV shows, and books. These communities extend beyond gameplay, enhancing the social experience gained through the game. Sites that cater to communities of play fit into three categories. Some collect and share user-generated collective intelligence on gameplay.10 Others are independent sites that operate as community organizers for gamers. Still others are maintained by the industry and focus on distributing promotional material provided by hardware manufacturers and game publishers.

Collective Intelligence

Gamers looking for tips and cheats provided by fellow players need only Google what they want. The largest of the sites devoted to sharing collective intelligence is the World of Warcraft wiki (http://wowwiki.com). Similar user-generated sites are dedicated to a range of digital games, including Age of Conan, Assassin’s Creed, Grand Theft Auto, Halo, Super Mario Bros., Metal Gear, Pokémon, Sonic the Hedgehog, and Spore.

Independent Sites

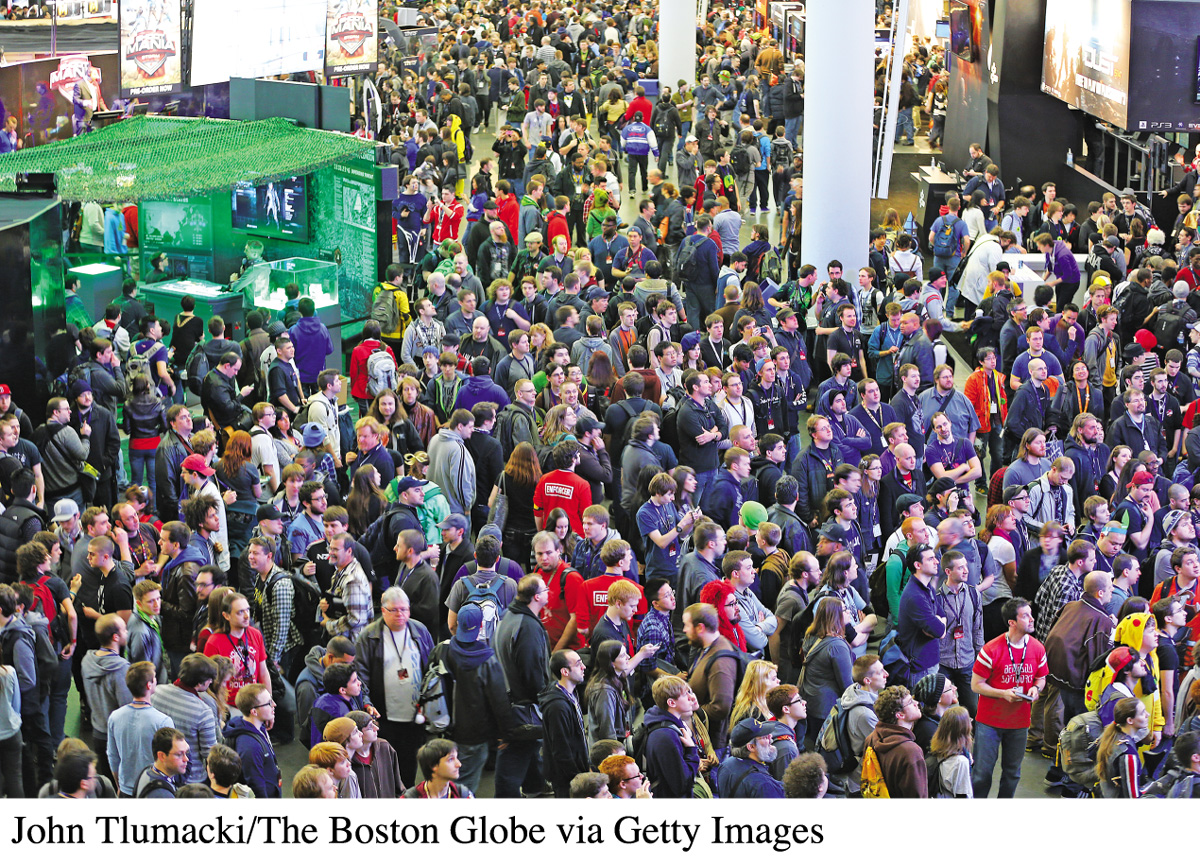

Penny-arcade.com is perhaps the best known of the independent community-building sites. Founded by Jerry Holkins and Mike Krahulik, the site started out as a Web comic focused on video game culture. It has since expanded to include forums and a Webcast called PATV, which documents behind-the-scenes work at Penny Arcade. Penny Arcade organizes a live festival for gamers called the Penny Arcade Expo (PAX), a celebration of gamer culture, and a children’s charity called Child’s Play.

Industry Sites

GameSpot.com and IGN.com are apt examples of the giant industry sites. GameSpot serves all the major gaming platforms and provides reviews, news, videos, cheats, and forums. It also has a culture section that features interviews with game designers and other creative artists. In 2011, GameSpot launched Fuse, a social networking service for gamers. IGN.com has most of the same services, as well as its Daily Fix—a regular Webcast about games.

Immersion and Addiction

As games and their communities have grown more elaborate and alluring, many players have spent more and more time immersed in them—a situation that can feed addictive behavior in some people. These deep levels of involvement are not always considered negative, however, especially within the media playground, but they are nonetheless issues to consider as gaming continues to evolve.

Immersion

For better or worse, gaming technology of the future promises experiences that will be more immersive, more portable, and more inclusive. As gaming matures as a mass medium, the industry will use its potential for immersion to attract different audiences seeking diverse experiences.

For example, the Wii’s system has successfully harnessed user-friendly motion-control technology to open up gaming to nontraditional players—women, senior citizens, and technophobes of all ages. More motion-controlled gaming is expected, with wireless controls to detect more of players’ body movements and even facial expressions. One version of this technology is Microsoft’s Kinect system, which uses a sensor camera to capture full-body player motion. The Kinect will also recognize players’ voices and faces, making on-screen avatars more accurate likenesses of the players. Used with Xbox LIVE, players can interact in full video or avatar form with friends online.

Another form of immersion has been imported from an older mass medium: In light of Hollywood’s great success with 3-D movies, television set production and video games have moved toward 3-D experiences. PlayStation rolled out 3-D games in the summer of 2010, followed shortly by Nintendo’s release of its 3DS—a 3-D version of its popular handheld console that doesn’t require special glasses.

These technological enhancements are being applied to existing entertainment brands, but video games in the future will also continue to move beyond entertainment. Games are already being used in workforce training, in military recruiting, for social causes, in classrooms, and as part of multimedia journalism. For instance, to accompany related news stories, the New York Times developed an interactive game called Gauging Your Distraction. The game demonstrates how distractions like cell phones affect a person’s driving ability. All of these developments continue to make games an ever-larger part of our media experiences—even for people who may not consider themselves avid gamers.

Addiction

No serious—and honest—gamer can deny the addictive qualities of digital gaming. In a 2011 study of more than three thousand third through eighth graders in Singapore, one in ten were considered pathological gamers, meaning that their gaming addiction was jeopardizing multiple areas of their lives, including school, social and family relations, and psychological well-being. Children with stronger addictions were more prone to depression, social phobias, and increased anxiety, which led to poorer grades in school. Singapore’s high percentage of pathological youth gamers is in line with studies from other countries, including the United States (8.5%), China (10.3%), and Germany (11.9%).11 Gender is a factor in game addiction: A 2013 study found that males are much more susceptible. This makes sense, given that the most popular games—action and shooter games—are heavily geared toward males.12

These findings are not entirely surprising, given that many digital games are not addictive by accident but rather by design. Just as “habit formation” is a primary goal of virtually every commercial form of digital media, from newspapers to television to radio, cultivating obsessive play is the aim of most game designs. From recognizing high scores to offering a variety of difficulty settings (encouraging players to try easy, medium, and hard versions) to embedding levels that gradually increase in difficulty, designers provide constant in-game incentives for obsessive play. This is especially true of multiplayer online games—such as Halo, Call of Duty, and World of Warcraft—which make money from long-term engagement by selling expansion packs or charging monthly subscription fees. These games have elaborate achievement systems with hard-to-resist rewards, including military ranks like “General” or fanciful titles like “King Slayer,” as well as special armor, weapons, and mounts (creatures your avatar can ride, including bears, wolves, and even dragons), all aimed at turning casual players into habitual ones.

This strategy of promoting habit formation may not differ from the cultivation of other media obsessions, like watching televised sporting events. Even so, real-life stories, such as that of the South Korean couple whose three-month-old daughter died of malnutrition while the negligent parents spent ten-hour overnight sessions in an Internet café raising a virtual daughter, bring up serious questions about video games and addiction. South Korea, one of the world’s most Internet-connected countries, is already sponsoring efforts to battle Internet addiction.13 Meanwhile, industry executives and others cite the positive impact of digital games, such as the learning benefits of games like SimCity and the health benefits of Wii Fit.