The Early History of American Advertising: 1850s to 1950s

Before the Industrial Revolution, most Americans lived in isolated areas and produced much of what they needed—tools, clothes, food—themselves. There were few products for sale, other than by merchants who offered additional goods and services in their own communities, so anything like modern advertising simply wasn’t necessary.

All that began changing in the 1850s with the Industrial Revolution and the linking of American villages and towns through railroads, the telegraph, and new print media. Merchants (such as patent medicine makers and cereal producers) wanted to advertise their wares in newspapers and magazines, giving rise to advertising agencies that managed these deals. These first national ads introduced the notion that it was important for sellers to differentiate their product from competing goods—which inspired more and more businesspeople to adopt advertising to drive sales.

Over the coming decades, all this fueled the growth of a consumer culture, in which Americans began desiring specific products and giving their loyalty to particular brands. Critics began decrying advertising’s power to seemingly dictate values and create needs in people—triggering the formation of watchdog organizations and careful consumers.

The First Advertising Agencies

The first American advertising agents were newspaper space brokers: individuals who purchased space in newspapers and then sold it to various merchants. Newspapers, accustomed to advertisers’ not paying their bills (or paying late), welcomed the space brokers, who paid up front. Brokers usually received discounts of 15 to 30 percent, then sold the space to advertisers at the going rate. In 1841, Volney Palmer opened the first ad agency in Philadelphia; for a 25 percent commission from newspaper publishers, he sold space to advertisers.

The first full-service modern ad agency, N. W. Ayer, introduced a different model: Instead of working for newspapers, the agency worked primarily for companies—or clients—that manufactured consumer products. Opening in 1869 in Philadelphia, N. W. Ayer helped develop, write, produce, and place ads in selected newspapers and magazines for its clients. The agency collected a fee from its clients for each ad placed, which covered the price that each media outlet charged for placement of the ad, plus a 15 percent commission. According to this model, the more ads an agency placed, the larger its revenue. Today, while the commission model still dominates, some advertising agencies now work for a flat fee, and some are paid on how well the ads they create drive sales for the client.

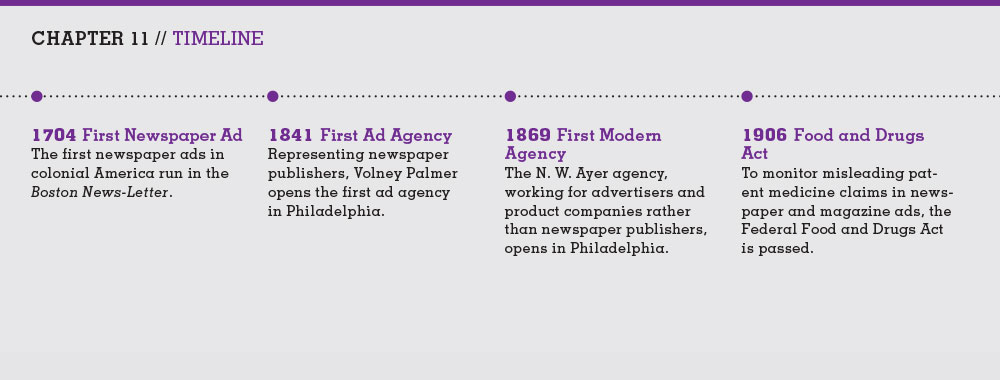

CHAPTER 11 // TIMELINE

1704 First Newspaper Ad

The first newspaper ads in colonial America run in the Boston News-Letter.

1841 First Ad Agency

Representing newspaper publishers, Volney Palmer opens the first ad agency in Philadelphia.

1869 First Modern Agency

The N. W. Ayer agency, working for advertisers and product companies rather than newspaper publishers, opens in Philadelphia.

1906 Food and Drugs Act

To monitor misleading patent medicine claims in newspaper and magazine ads, the Federal Food and Drugs Act is passed.

1914 FTC

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) is established by the federal government to help monitor advertising abuses.

1940s The War Advertising Council

A voluntary group of ad agencies and advertisers organizes war bond sales, blood donor drives, and scarce-goods rationing.

1971 TV Tobacco Ban

Tobacco ads are banned on TV following a government ruling.

1988 Joe Camel

Joe Camel is revived as a cartoon character from an earlier print media campaign; the percentage of teens smoking Camels rises.

1989 Channel One

Channel One is introduced into thousands of schools, offering “free” equipment in exchange for ten minutes of news programming and two minutes of commercials.

1998 Billboard Tobacco Ban

The tobacco industry agrees to a settlement with several states, and tobacco ads are banned on billboards.

1990s Beer Ads on TV

Budweiser uses cartoon-like animal characters to appeal to young viewers.

2007 TV Ad Time

Fifteen minutes of each hour of prime-time network TV contains ads.

2013 Mega-Agencies

Four international mega-agencies—Omnicom, Interpublic, WPP, and Publicis—control more than half of the world’s ad revenues.

2015 Super Bowl Record

The average cost of a thirty-second spot during the Super Bowl reaches $4.5 million.

Click on the timeline above to see the full, expanded version.

Retail Stores: Giving Birth to Branding

During the mid-1800s, most manufacturers sold their goods directly to retail store owners, who usually set their own prices by purchasing products in large quantities. Stores would then sell these loose goods—from clothing to cereal—in large barrels and bins, so customers had no idea who made them. This arrangement shifted after manufacturers started using newspaper advertising to create brand names—that is, to differentiate their offerings and their company’s image from those of their competitors in the minds of consumers and retailers—even if the goods were basically the same. For example, one of the earliest brand names, Quaker Oats (the first cereal company to register a trademark in the 1870s), used the image of William Penn, the Quaker who founded Pennsylvania in 1681, in its ads to project a company image of honesty, decency, and hard work.

Consumers, convinced by the ads, began demanding certain products. And retail stores felt compelled to stock the desired brands. This enabled manufacturers, not the retailers, to begin setting the prices of their goods—confident that they’d prevail over the stores’ anonymous bulk items. Indeed, product differentiation in brand-name packaged goods represents advertising’s single biggest triumph. Though most ads don’t trigger a large jump in sales in the short run, over time they create demand by leading consumers to associate particular brands with qualities and values important to them.

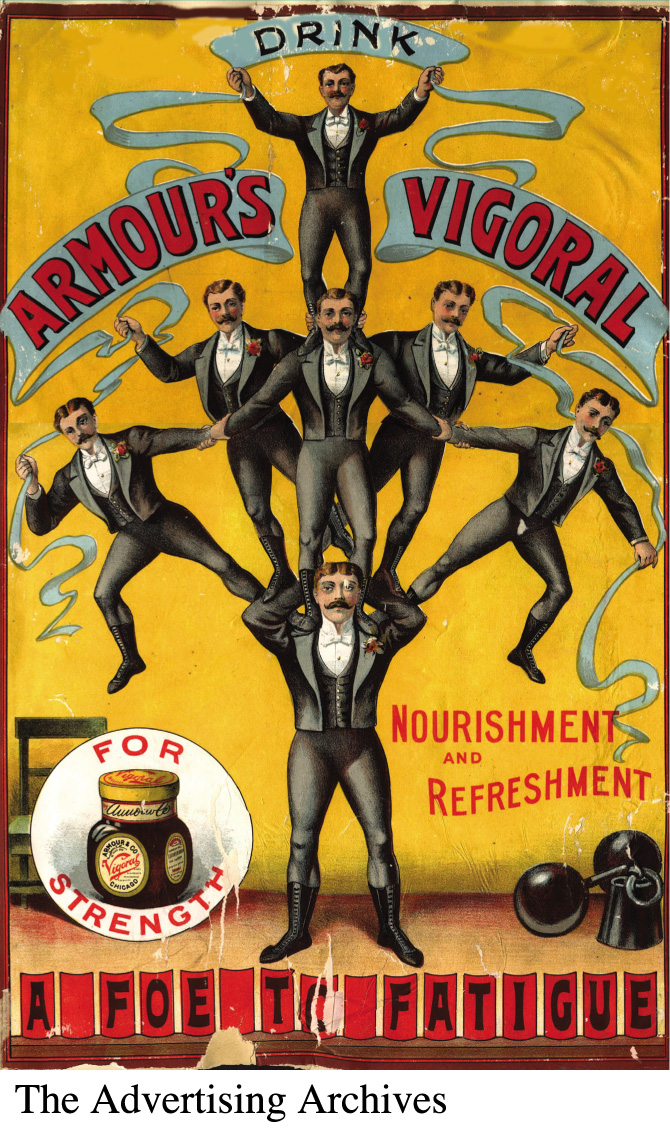

Patent Medicines: Making Outrageous Claims

As the nineteenth century marched on, patent medicine makers, excited by advertising’s power to differentiate their products, invested heavily in print ads developed and placed by ad agencies. But many patent medicines (which consisted of mostly water and high concentrations of ethyl alcohol) made outrageous claims about the medical problems they could cure. The misleading ads spawned public cynicism. As a result, advertisers began to police their own ranks and developed industry codes to restore consumers’ confidence. Partly to monitor patent medicine claims, Congress passed the Federal Food and Drugs Act in 1906.

Department Stores: Fueling a Consumer Culture

Along with patent medicine makers, department stores began advertising heavily in newspapers and magazines in the late nineteenth century. By the early 1890s, more than 20 percent of ad space in these media was devoted to department stores.

By selling huge volumes of goods and providing little individualized service, department stores saved a lot of money—and passed these savings on to customers in the form of lower prices (as Target and Walmart do today). The department stores thus lured customers away from small local stores, making even more money that they could reinvest in advertising. This development further fueled the growth of a large-scale consumer culture in the United States.

Transforming American Society

By the dawn of the twentieth century, advertising had become pervasive in the United States. As it gathered force, it began transforming American society. For one thing, by stimulating demand among consumers for more and more products, advertising helped manufacturers create whole new markets. The resulting brisk sales also enabled companies to recover their product-development costs quickly. In addition, advertising made people hungry for technological advances by showing how new machines—vacuum cleaners, washing machines, cars—might make daily life easier or better. All this encouraged economic growth by increasing sales of a wide range of goods.

Advertising also began influencing Americans’ values. As just one example, ads for household-related products (mops, cleaning solutions, washing machines) conveyed the message that “good” wives were happy to vanquish dirt from their homes. By the early 1900s, business leaders and ad agencies believed that women, who constituted as much as 70 to 80 percent of newspaper and magazine readerships, controlled most household purchasing decisions. Agencies developed simple ads tailored to supposedly feminine characteristics—ads featuring emotional and even irrational content. For instance, many such ads portrayed cleaning products and household appliances as “heroic” and showed grateful women gushing about how the product “saved” them from the shame of a dirty house or the hard labor of doing laundry by hand.

Early Regulation of Advertising

During the early 1900s, advertising’s growing clout—along with revelations of fraudulent advertising claims and practices—catalyzed the formation of the first watchdog organizations. For example, advocates in the business community in 1913 created the nonprofit Better Business Bureau, whose mission included keeping tabs on deceptive advertising. The following year, the government established the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), in part to help monitor advertising abuses. Alarmed by government’s willingness to step in, players in the advertising industry urged self-regulation to keep government interference at bay.

At the same time, advertisers recognized that a little self-regulation could benefit them in other ways as well. They especially wanted a formal service that tracked newspaper and magazine readership, guaranteed accurate audience measures, and ensured that newspapers didn’t overcharge agencies and their clients. To that end, publishers formed the Audit Bureau of Circulation (ABC) in 1914 to monitor circulation figures. In 2012, the group changed the name of its North American operations to Alliance for Audited Media, a rebranding partly aimed at staying relevant in a time of emerging digital newspaper and magazine business.

But it wasn’t until the 1940s that the industry began to deflect the long-standing criticisms that advertisers created needs that consumers never knew they had, dictated values, and had too strong a hand in the economy. To promote a more positive self-image, the ad industry developed the War Advertising Council. This voluntary group of ad agencies and advertisers began organizing war bond sales, blood donor drives, and scarce-goods rationing. Known today by a broader mission and its postwar name, the Ad Council chooses a dozen worthy causes annually and produces pro bono public service announcements (PSAs) aimed at combating social problems, such as illiteracy, homelessness, drug addiction, smoking, and AIDS.

With the advent of television in the 1950s, advertisers had a brand-new visual medium for reaching consumers. Critics complained about the increased intrusion of ads into daily family life. They especially decried what was then labeled subliminal advertising. Through this tactic, TV ads supposedly used hidden or disguised print and visual messages (often related to sex, like the shape of a woman’s body in an ice cube for a vodka ad) that allegedly register only in viewers’ subconscious minds, fooling them into buying products they don’t need. However, research has reported over the years that subliminal ads are no more powerful than regular ads. Demonstrating a willingness to self-regulate, though, the National Association of Broadcasters banned the use of anything resembling a subliminal-type ad in 1958.