Persuasive Techniques in Contemporary Advertising

In addition to using a similar organizational structure, most ad agencies employ a wide variety of persuasive techniques in the ad campaigns they create for their clients. Indeed, persuasion—getting consumers to buy one company’s products and services and not another’s—lies at the core of the advertising industry. Persuasive techniques take numerous forms, ranging from conventional strategies (such as having a famous person endorse a product) to not-so-conventional strategies (for instance, showing video game characters using a product).

Do these tactics work—that is, do they boost sales? This is a tough question, because it’s difficult to distinguish an ad’s impact on consumers from the effects of other cultural and social forces. But companies continue investing in advertising on the assumption that without the product and brand awareness that advertising builds, consumers just might go to a competitor.

Using Conventional Persuasive Strategies

Advertisers have long used a number of conventional persuasive strategies.

Famous-person testimonial: A product is endorsed by a well-known person. For example, Serena Williams has become a leading sports spokesperson, having appeared in ads for such companies as Nike, Kraft Foods, and Procter & Gamble.

Plain-folks pitch: A product is associated with simplicity. For instance, General Electric (“Imagination at work”) and Microsoft (“Your potential. Our passion”) have used straightforward slogans stressing how new technologies fit into the lives of ordinary people.

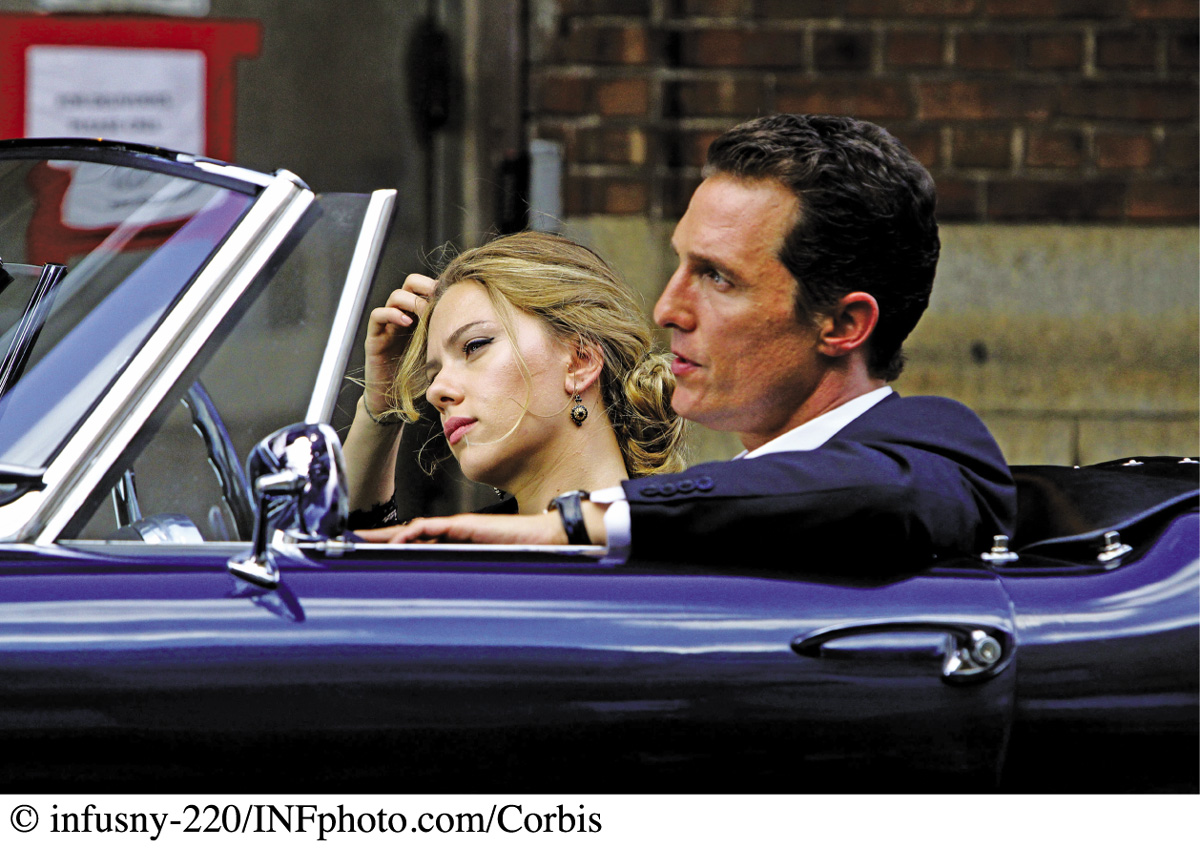

Snob appeal: An ad attempts to persuade consumers that using a product will maintain or elevate their social status. Advertisers selling jewelry, perfume, clothing, and luxury automobiles often use snob appeal.

Bandwagon effect: The ad claims that “everyone” is using a particular product. Brands that refer to themselves as “America’s favorite” or “the best-selling” imply that consumers will be “left behind” if they ignore these products.

Hidden-fear appeal: A campaign plays on consumers’ sense of insecurity. Deodorant, mouthwash, and shampoo ads often tap into people’s fears of having embarrassing personal hygiene problems if they don’t use the suggested product.

Irritation advertising: An ad creates product-name recognition by being annoying or obnoxious. (You may have seen one of these on TV, in the form of a local car salesman loudly touting the “UNBELIEVABLE BARGAINS!” available at his dealership.)

Associating Products with Values

In addition to the conventional persuasive techniques just described, ad agencies draw on the association principle in many campaigns for consumer products. Through this technique, the agency associates a product with a positive cultural value or image—even if that value or image has little connection to the product. For example, many ads displayed visual symbols of American patriotism in the wake of the 9/11 terrorist attacks in an attempt to associate products and companies with national pride.

Yet this technique has also been used to link products with stereotyped caricatures of targeted consumer groups, such as men, women, or specific ethnic groups. For example, many ads have sought to appeal to women by portraying men as idiots who know nothing about how to use a washing machine or how to heat up leftovers for dinner. The assumption is that portraying men as idiots will make women feel better about themselves—and thus be attracted to the advertised product (see “Media Literacy Case Study: Idiots and Objects: Stereotyping in Advertising” on pages 382–383).

Another popular use of the association principle is to claim that products are “real” and “natural”—possibly the most common adjectives used in advertising. For example, Coke sells itself as “the real thing.” The cosmetics industry offers synthetic products that make us look “natural.” And “green” marketing touts products that are often manufactured and not always environmentally friendly.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Philip Morris used the association principle to transform the image of its Marlboro filtered cigarette brand (considered a product for women in the 1920s) into a product for men. Ad campaigns featured images of active, rugged males, particularly cowboys. Three of the men who appeared in these ad campaigns eventually died of lung cancer caused by cigarette smoking. But that apparently hasn’t blunted the brand’s impact. By 2014, the branding consultancy BrandZ had named Marlboro the world’s ninth “most powerful [memorable] brand,” having an estimated worth of $67.3 billion. (Google, Apple, and IBM were the top three rated brands; see Table 11.1.)

| Rank | Brand | Brand Value ($Millions) | Brand Value Change, 2014 vs. 2013 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 158,843 | 40 | |

| 2 | Apple | 147,880 | –20 |

| 3 | IBM | 107,541 | –4 |

| 4 | Microsoft | 90,185 | 29 |

| 5 | McDonalds | 85,706 | –5 |

| 6 | Coca-Cola* | 80,683 | 3 |

| 7 | Visa | 79,197 | 41 |

| 8 | AT&T | 77,883 | 3 |

| 9 | Marlboro | 67,341 | –3 |

| 10 | Amazon.com | 64,255 | 41 |

*Coca-Cola includes Diet Coke, Coke Light, and Coke Zero.

Data from: “BrandZ Top 100 Most Powerful Brands 2014,” Millward Brown Optimor, www.millwardbrown.com/brandz/2014/Top100/Docs/2014_BrandZ_Top100_Chart.pdf

Telling Stories

Many ads also tell stories that contain elements found in myths (narratives that convey a culture’s deepest values and social norms). For example, an ad might take the shape of a mini-drama or sitcom, complete with characters, settings, and plots. Perhaps a character experiences a conflict or problem of some type. The character resolves the situation by the end of the ad, usually by purchasing or using the product. The product and those who use it emerge as the heroes of the story.

For instance, in the early 2000s, ads for GEICO car insurance featured TV commercials that looked like thirty-second sitcoms. The ad’s plot lines told the story of cavemen trying to cope in the modern world but who found themselves constantly ridiculed—for being cavemen (“so easy a caveman can do it”). The point of the ads included associating the product with humor, making the audience feel superior to dim-witted prehistoric guys. The ads were funny and popular, and ABC actually commissioned a short-lived sitcom called Cavemen based on the ads’ characters.

Although most of us realize that ads telling stories create a fictional world, we often can’t help but get caught up in them. That’s because they reinforce our values and assumptions about how the world works. And they reassure us that by using familiar brand names—packaged in comforting mini-stories—we can manage the everyday tensions and problems that confront us.

Placing Products in Media

Product placement—strategically placing ads or buying space in movies, TV shows, comic books, and video games so that they appear as part of a story’s set environment—is another persuasive strategy ad agencies use. For example, the 2010 movie Iron Man 2 features product placements from over sixty brands, almost triple the number shown in the original 2008 film, which included prominent use of brands like Burger King, Audi, and LG mobile. The NBC sitcom 30 Rock even made fun of product placement, satirizing how widespread it had become. In one scene, the actors talk about how great Diet Snapple is. Then an actual commercial for Snapple appears.

Many critics argue that product placement has gotten out of hand. In 2005, watchdog organization Commercial Alert asked both the FTC and the FCC to mandate that consumers be warned about product placement in television shows. The FTC rejected the petition, and by 2008 the FCC had still made no formal response to the request. Most defenders of product placement argue that there is little or no concrete evidence or research that this practice harms consumers. The 2011 documentary POM Wonderful Presents: The Greatest Movie Ever Sold takes a satirical look at product placement—and filmmaker Morgan Spurlock financed the film’s entire budget using that very strategy.