Commercial Speech and Regulating Advertising

Advertisements are considered commercial speech—defined as any print or broadcast expression for which a fee is charged to organizations and individuals buying time or space in the mass media. Though the U.S. Constitution’s First Amendment protects freedom of speech and of the press, it doesn’t specify whether advertisers can say anything they want in their commercial speech; thus, the question of whether commercial speech is protected by the Constitution is tricky. In some critics’ view, certain forms of advertising can have destructive consequences and therefore should be regulated. These include ads that target children, that tout unhealthy products (such as alcohol and tobacco), that prompt people to adopt dangerous behaviors (such as starving themselves to look like models in magazines), and that hawk prescription medications directly to consumers instead of to doctors.

Advertising and Effects on Children

Scholars and advertisers analyze the effects of advertising on children.

Discussion: In the video, some argue that using cute, kid-friendly imagery in alcohol ads can lead children to begin drinking; others dispute this claim. What do you think, and why?

To be sure, no one has figured out just how much power such ads have to actually influence target consumers. Indeed, studies have suggested that 75 to 90 percent of new consumer products fail because the buying public doesn’t embrace them—suggesting that advertising isn’t as effective as some critics might think.6 Nevertheless, serious concerns over the impact of advertising persist.

Targeting Children and Teens

Because children and teenagers may influence billions of dollars each year in family spending—on everything from snacks to cars—advertisers have increasingly targeted them, often viewing young people as “consumers in training.” When ads influence youngsters in a good way (for example, by getting them interested in reading books), no one complains about advertising’s power. It’s when ads influence kids and teens in what is perceived as a dangerous way (such as tempting them with unhealthy foods) that concerns arise.

For years, groups such as Action for Children’s Television (ACT) worked to limit advertising aimed at children (especially ads promoting toys associated with a show). In addition, parent groups have pushed to limit the heavy promotion of unhealthy products like sugar-coated cereals during children’s TV programs. Congress has responded weakly, hesitant to question the First Amendment’s protection of commercial speech and pressured by determined lobbying from the advertising industry. The Children’s Television Act of 1990 mandated that networks provide some educational and informational children’s programming, but the act has been difficult to enforce and has done little to restrict advertising aimed at kids.

In addition to trying to control TV advertising aimed at young people, critics have complained about advertising that has encroached on school property. The introduction of Channel One into thousands of schools during the 1989–90 school year has been one of the most controversial cases of in-school advertising. The brainchild of advertising firm Whittle Communications, Channel One offered free video and satellite equipment (tuned exclusively to Channel One) in exchange for a twelve-minute package of current events programming that included two minutes of commercials.

Over the years, the National Dairy Council and other organizations have also used schools to promote products—for example, by providing free filmstrips, posters, magazines, folders, and study guides adorned with member companies’ logos. Many teachers, especially in underfunded districts, have been grateful for these free materials. However, many parent and teacher groups have objected to Channel One (now in about eight thousand middle and high schools in the United States), which in their view requires teens to watch commercial messages in a learning environment.

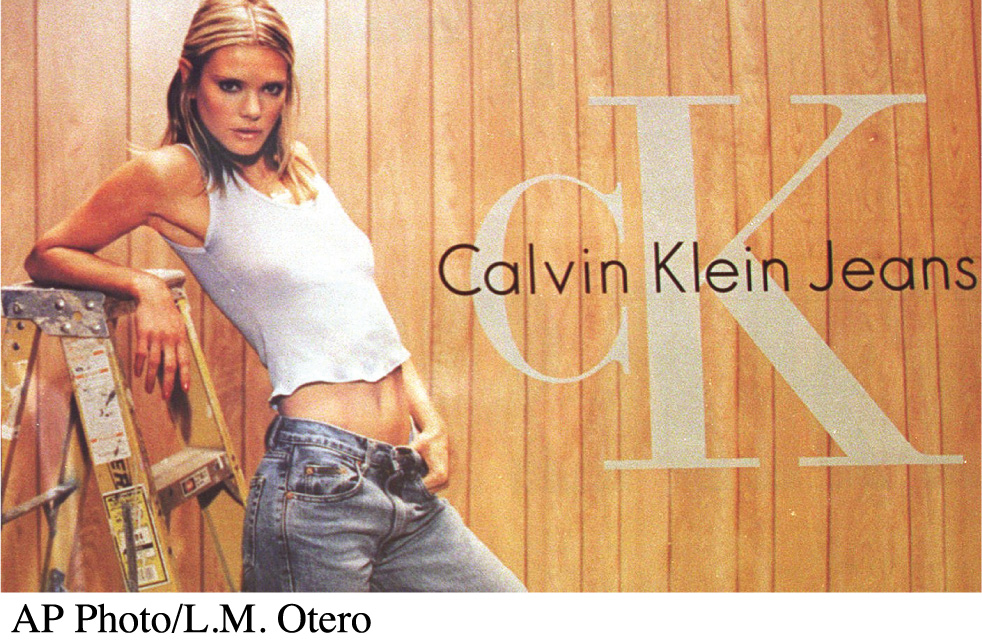

Triggering Anorexia and Overeating

Some critics accuse ads of contributing to anorexia among girls and women; others, of contributing to obesity among young and adult Americans. To be sure, companies have long marketed fashions and cosmetics by showing ultrathin female models using their products. Through such campaigns, advertising strongly shapes standards of beauty in our culture. Many girls and women apparently feel compelled to achieve those standards—even if it means starving themselves or having repeated cosmetic surgeries.

At the same time, advertising has been blamed for the tripling of obesity rates in the United States since the 1980s. Corn-syrup-laden soft drinks, fast food, junk food, and processed food are the staples of media advertising. Critics maintain that advertisements for fattening products have directly contributed to widespread obesity in the United States. The food and restaurant industry has denied this connection. Industry advocates claim that people have the power to decide what they eat—and many individuals are making poor choices, such as eating too much fast food.

Promoting Smoking

One of the most sustained criticisms of advertising is its promotion of tobacco consumption. Each year, an estimated 400,000 Americans die from diseases related to nicotine addiction and poisoning. Still, for a long time tobacco companies kept cranking out ad campaigns designed to win over new customer segments, which often included teenagers.

The government’s position regarding the tobacco industry began changing in the mid-1990s. At that time, new reports revealed that tobacco companies had known that nicotine was addictive as far back as the 1950s and had withheld that information from the public. Settlements between the industry and states have put significant limits on advertising and marketing of tobacco products. For example, ads cannot use cartoon characters such as Joe Camel, because such characters appeal to young people. And companies can’t show ads on billboards or in subway or commuter trains, where young people might be vulnerable to them. In June 2009, President Obama, himself a professed addicted smoker since his teen years, signed the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act. The act allows the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to lessen the nicotine in tobacco products and block misleading cigarette-packaging labels that say “low tar” and “light.” Despite these restrictions, tobacco companies still spend about $9 billion annually on U.S. advertisements—more than twenty times the amount spent on anti-tobacco public service spots.

Promoting Drinking

In 2013, 88,000 people in the United States died from alcohol-related diseases; another 10,000 lost their lives in car crashes involving drunk drivers. Many of the same complaints regarding tobacco advertising are also being leveled at alcohol ads. For example, critics have protested that one of the most popular beer campaigns of the late 1990s—featuring a trio of frogs croaking Budweis-errrr—used cartoon-like animal characters to appeal to young viewers. Some alcohol ads, such as Pabst Brewing Company’s ads featuring Snoop Dogg for Blast by Colt 45 (a strong flavored malt beverage that the Massachusetts attorney general called “binge-in-a can”), have targeted young minority populations specifically.

The alcohol industry has also heavily targeted college students with ads, especially for beer. The images and slogans in alcohol ads often associate the products with power, romance, sexual prowess, or athletic skill. In reality, though, alcohol is a depressant: It diminishes athletic ability and sexual performance, triggers addiction in as much as 10 percent of the U.S. population, and factors into many domestic-abuse cases. Thus, many ads present a false impression of what alcohol products can do for consumers.

Hawking Drugs Directly to Consumers

New advertising tactics by the pharmaceutical industry—such as marketing directly to consumers instead of to doctors—have also drawn fire from critics worried about vulnerable groups of consumers. According to a study by the Kaiser Family Foundation, from 1994 to 2007, spending on direct-to-consumer advertising for prescription drugs soared from $266 million to $5.3 billion. About two-thirds of such ads are shown on television, and they’ve proved effective for the pharmaceutical companies that invest in and use them. A survey found that nearly one in three adults has talked to a doctor about a particular drug after seeing an ad for it on TV, and one in eight subsequently received a prescription. The tremendous growth of prescription drug ads brings with it the potential for misleading or downright false claims. That’s because a brief TV advertisement can’t effectively communicate all of the cautionary information consumers need to know about these medications.

Monitoring the Advertising Industry

Worried about advertising’s power over vulnerable consumers, a few nonprofit watchdog and advocacy organizations, such as Commercial Alert and the American Legacy Foundation, have emerged. Such groups strive to compensate for some of the shortcomings of the FTC and other government agencies in monitoring false and deceptive ads and the excesses of commercialism. At the same time, the FTC is still trying to combat the negative impact of advertising, though its effectiveness remains questionable, especially in light of cutbacks at the agency that have been going on since the 1980s.

Commercial Alert

Since 1998, Commercial Alert has worked to “limit excessive commercialism in society.” Founded in part with help from longtime consumer advocate Ralph Nader, Commercial Alert became a project of Public Citizen, a nonprofit consumer protection organization based in Washington, D.C. In addition to its efforts to check commercialism, Commercial Alert has challenged specific marketing tactics that allow corporations to intrude into civic life. In 2012, Commercial Alert objected to the state of Kentucky’s proposal to sell advertising on school buses. The group argued that “children need a sanctuary from a world where everything seems to be for sale.” In constantly questioning the role of advertising in our democracy, Commercial Alert has aimed to strengthen noncommercial culture and limit the amount of corporate influence on publicly elected government officials and organizations.

The American Legacy Foundation

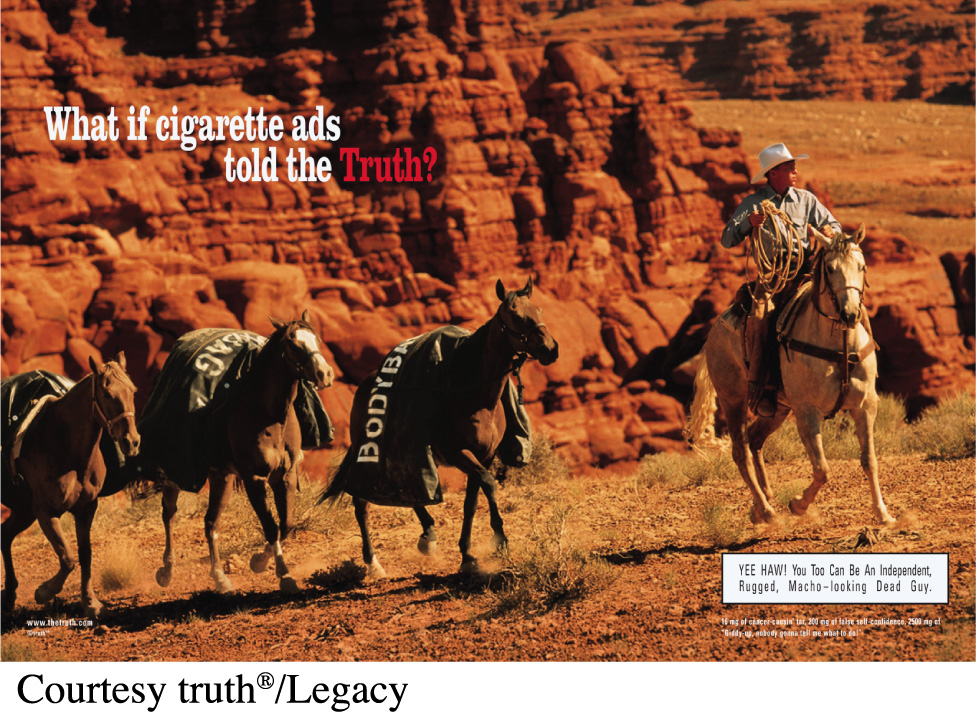

Some nonprofit organizations have used innovative advertising of their own to offset the effects of ads for dangerous products. In 2000, the American Legacy Foundation launched an anti-smoking/anti–tobacco industry ad campaign called “Truth.” The campaign’s mission has been to counteract tobacco marketing and reduce tobacco use among young people. The “Truth” project uses print and television ads that contradict the images that have long been featured in cigarette ads. For example, one of their early spots showed a giant rat expiring on a city sidewalk, clutching a cardboard sign saying that cigarettes contain the same chemical found in rat poison. All “Truth” spots prominently reference the foundation’s Web site, www.thetruth.com, which offers statistics, discussion forums, and outlets for teen creativity, such as games.

The FTC

Through its truth-in-advertising rules, the FTC has played an investigative role in substantiating the claims of various advertisers. Thus, the organization contributes to some regulation of the ad industry. The FTC usually permits a certain amount of puffery—ads featuring hyperbole and exaggeration—particularly when an ad describes a product as “new and improved.” However, the FTC defines ads as deceptive when they are likely to mislead reasonable consumers through statements made, images shown, or omission of certain information. (For example, in some Campbell Soup ads once featuring images of a bowl of soup, marbles had been placed in the bottom of the bowl to push bulkier ingredients to the surface. This was deceptive advertising because it made the soup look less watery than it really was.) Moreover, when an advertiser makes comparative claims for a product, such as it’s “the best,” “the greatest,” or “preferred by four out of five doctors,” FTC rules require statistical evidence to back up the claims.

When the FTC discovers deception in advertising, it usually requires advertisers to change or remove the ads from circulation. The FTC can also impose monetary civil penalties, which are paid to consumers. And it occasionally requires an advertiser to run spots correcting the deceptive ads.