The Origins of Free Expression and a Free Press

In the United States, freedom of speech and freedom of the press are protected by the First Amendment in the Bill of Rights, developed for our nation’s Constitution. Roughly interpreted, these freedoms suggest that anyone should be able to express his or her views, and that the press should be able to publish whatever it wants, without prohibition from Congress. But there’s always been a tension between the notion of “free expression” and the idea that some expression (such as sexually explicit words or images) should be prohibited or censored. Many people have wondered what free expression really means.

In this section, we examine several aspects of free speech and freedom of the press. We explore the roots of the First Amendment and different interpretations of free expression that have arisen in modern times. We look at evolving notions of censorship and forms of expression that are not protected by the U.S. Constitution. And we consider ways in which the First Amendment has clashed with the Sixth Amendment, which guarantees accused individuals the right to speedy and public trials by impartial juries.

A Closer Look at the First Amendment

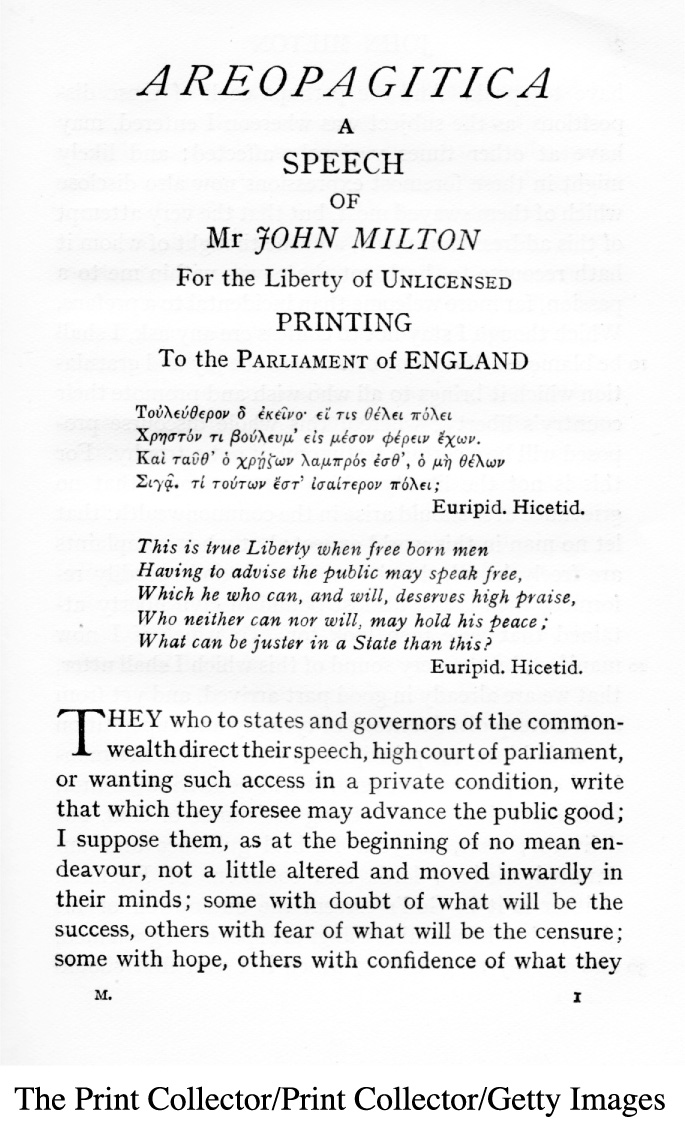

To understand how the idea of free expression has developed in the United States, we must understand how the notion of a free press came about. The story goes back to the 1600s, when various national governments in Europe controlled the circulation of ideas through the press by requiring printers to obtain licenses from them. Their goal was to monitor the ideas published by editors and writers and swiftly suppress subversion. However, in 1644, English poet John Milton published his essay Areopagitica, which opposed government licenses for printers and defended a free press. Milton argued that in a democratic society, all sorts of ideas—even false ones—should be allowed to circulate. Eventually, he maintained, the truth would emerge. In 1695, England stopped licensing newspapers, and most of Europe followed suit. In many democracies today, publishing a newspaper, magazine, or newsletter requires no license.

Less than a hundred years later, the writers of the U.S. Constitution were ambivalent about the idea of a free press. Indeed, the version of the Constitution ratified in 1788 did not include such protection. The states took a different tack, however. At that time, nine of the original thirteen states had charters defending freedom of the press. These states pushed to have federal guarantees of free speech and the press approved at the first session of the new Congress. Their efforts paid off: The Bill of Rights, which contained the first ten amendments to the Constitution, won ratification in 1791.

However, commitment to freedom of the press was not yet tested. In 1798, the Federalist Party, which controlled the presidency and the Congress, passed the Sedition Act to silence opposition to an anticipated war against France. The act was signed into law by President John Adams and resulted in the arrest and conviction of several publishers. However, after failing to curb opposition, the Sedition Act expired in 1801, during Thomas Jefferson’s presidency. Jefferson, a Democratic-Republican who had challenged the act’s constitutionality, pardoned all defendants convicted under it.4 Ironically, the Sedition Act—the first major attempt to constrain the First Amendment—ended up solidifying American support behind the notion of a free press.

Interpretations of Free Expression

Americans are not alone in debating what constitutes free expression and whether constraining expression is ever appropriate. Over time, four models have emerged that capture the widely differing interpretations of what “free expression” means.5 We can think of these as the authoritarian, state, social responsibility, and libertarian models. These models are distinguished by the degree of freedom their proponents advocate, and by ruling classes’ attitudes toward the freedoms granted to average citizens.

The Authoritarian Model

The authoritarian model developed around the time the printing press first arrived in sixteenth-century England. Under this model, criticism of government and public dissent were not tolerated, especially if such speech undermined “the common good”—an ideal that elites and rulers defined. The government actively censored any expression it found threatening, and it issued printing licenses only to those publishers willing to say positive things about the government. Today, this model persists in many developing countries that have authoritarian governments. In these nations, journalism’s job is to support government and business efforts to foster economic growth, minimize political dissent, and promote social stability.

The State Model

Under the state model, the government controls the press and what it reports. Leaders believe that the press should serve the goals of the state. Although the government tolerates some criticism, it suppresses ideas that challenge the basic premises of state authority. Today, a few countries use this model, including Myanmar (Burma), China, Cuba, and North Korea.

The Social Responsibility Model

The social responsibility model captures the ideals of mainstream journalism in the United States and most other democracies. The concepts and assumptions behind this model were outlined in 1947 by the Hutchins Commission, which was formed to examine the press’s increasing influence. The commission’s report called for the development of press watchdog groups, on the assumption that the mass media had grown too powerful. The report also concluded that the press needed to take more responsibility for improving American society by providing services like news forums for the exchange of ideas and better coverage of social groups and society’s range of economic classes.

The social responsibility model has roots in revolutionary Europe. This model calls for the press to be privately owned, so that newspapers operate independently of government. By doing so, the press functions as a Fourth Estate—an unofficial branch of government that watches for abuses of power by the legislative, judicial, and executive branches. The press supplies information about such abuses to citizens, so they can make informed decisions about political and social issues.

The Libertarian Model

The libertarian model is the flip side of both the state and the authoritarian models and an extension of the social responsibility model. This model encourages vigorous criticism of government and supports the highest degree of individual and press freedoms. Proponents of the libertarian model argue that no restrictions should be placed on the mass media or on individual speech. In North America and Europe, many alternative newspapers and magazines operate on such a model. They often emphasize the importance of securing rights for sidelined populations (such as gay men and lesbians), and follow an ethic that absolute freedom of expression is the best way to fight injustice and arrive at the truth.

The Evolution of Censorship

In the United States, the First Amendment theoretically prohibits censorship. Over time, Supreme Court decisions have defined censorship as prior restraint—meaning that courts and governments cannot block any publication or speech before it actually occurs. The principle behind prior restraint is that a law has not been broken until an illegal act has been committed. However, the Court left open the idea that the judiciary could halt publication of news in exceptional cases—for example, if such publication would threaten national security. In the 1970s, two pivotal court decisions tested the idea of prior restraint.

The Pentagon Papers Decision

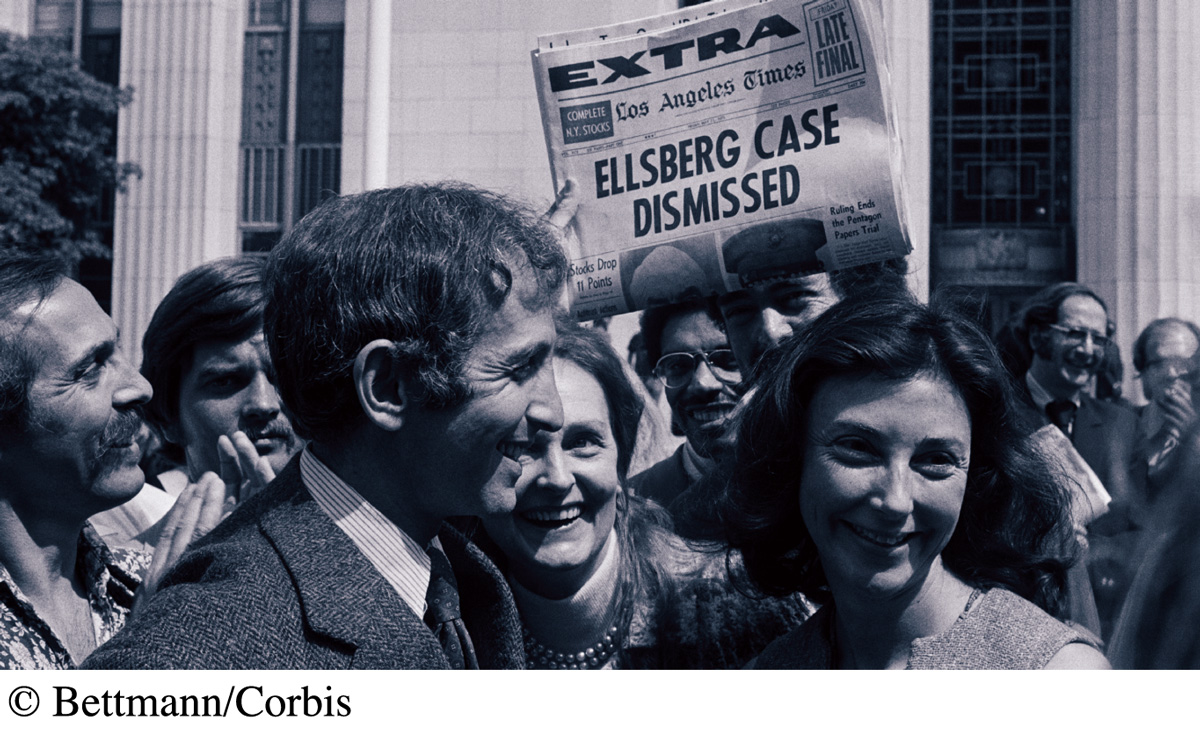

In 1971, with the Vietnam War still raging, Daniel Ellsberg, a former Defense Department employee, stole a copy of the forty-seven-volume report “History of U.S. Decision-Making Process on Vietnam Policy.” A thorough study of U.S. involvement in Vietnam since World War II, the report was classified by the government as top secret. Ellsberg and a friend leaked the report—nicknamed the Pentagon Papers—to the New York Times and the Washington Post. In June 1971, the Times began publishing excerpts of the report. To block any further publication, the Nixon administration applied for and received a federal court injunction against the Times to halt publication of the documents, arguing that it posed “a clear and present danger” to national security by revealing military strategy to the enemy.

In a 6–3 vote, the Supreme Court sided with the newspaper. Justice Hugo Black, in his majority opinion, attacked the government’s attempt to suppress publication: “Both the history and language of the First Amendment support the view that the press must be left free to publish news, whatever the source, without censorship, injunctions, or prior restraints.”6

The Progressive Magazine Decision

The conflict between prior restraint and national security surfaced again in 1979, when the U.S. government issued an injunction to block publication of the Progressive, a national left-wing magazine. The editors had planned to publish an article titled “The H-Bomb Secret: How We Got It, Why We’re Telling It.” The dispute began when the magazine’s editor sent a draft to the Department of Energy to verify technical portions of the article. Believing that the article contained sensitive data that might damage U.S. efforts to halt the proliferation of nuclear weapons, the department asked the magazine not to publish it. When the magazine said it would proceed anyway, the government sued the Progressive and asked a federal district court to block publication.

In an unprecedented action, Justice Robert Warren sided with the government, deciding that “a mistake in ruling against the United States could pave the way for thermonuclear annihilation for us all. In that event, our right to life is extinguished and the right to publish becomes moot.”7 Warren was seeking to balance the Progressive’s First Amendment rights against the possibility that the article, if published, would spread dangerous information and undermine national security. During appeals, several other publications printed their own stories about the H-bomb, and the U.S. government eventually dropped the case. None of the articles, including one ultimately published by the Progressive, contained precise details on how to design a nuclear weapon. But Warren’s decision represented the first time in American history that a prior-restraint order imposed in the name of national security stopped initial publication of a news report.

Unprotected Forms of Expression

Despite the First Amendment’s provision that “Congress shall make no law” restricting speech and the press, the federal government, state laws, and even local ordinances have on occasion curbed some forms of expression. And over the years, the U.S. court system has determined that some kinds of expression do not merit protection under the Constitution. These forms include sedition, copyright infringement, libel, obscenity, and violation of privacy rights.

Sedition

For more than a century after the Sedition Act of 1798, Congress passed no laws prohibiting the articulation or publication of dissenting opinions. But sentiments that fueled the Sedition Act resurfaced in the twentieth century, particularly in times of war. For instance, the Espionage Acts of 1917 and 1918—enforced during the two world wars—made it a federal crime to utter or publish “seditious” statements, defined as anything expressing opposition to the U.S. war effort.

For example, in the landmark Schenck v. United States (1919) appeal case, taking place during World War I, the Supreme Court upheld the conviction of a Socialist Party leader, Charles T. Schenck, for distributing leaflets urging American men to protest the draft. Justices argued that Schenck had violated the recently passed Espionage Act.

In supporting Schenck’s sentence—a ten-year prison term—Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes noted that the Socialist leaflets were entitled to First Amendment protection, but only during times of peace. In establishing the “clear and present danger” criterion for expression, the Supreme Court demonstrated the limits of the First Amendment.

Copyright Infringement

Appropriating a writer’s or an artist’s words, images, or music without consent or payment is also a form of expression not protected by the First Amendment. A copyright legally protects the rights of authors and producers to their published or unpublished writing, music, lyrics, TV programs, movies, or graphic art designs. Congress passed the first Copyright Act in 1790, which gave authors the right to control their published works for fourteen years, with the opportunity to renew copyright protection for another fourteen years. After the end of the copyright period, the work would enter the public domain, which would give the public free access to the work. (For example, a publisher could reprint a written work that had entered the public domain.) The idea was that a period of copyright control would give authors financial incentive to create original works, and that moving works into the public domain would give others incentive to create works derived from earlier accomplishments.

But in time, artists, as they began to live longer, and corporations, which could also hold copyrights, wanted to prolong the period in which they could profit from creative works. In 1976, Congress extended the copyright period to the life of the author plus fifty years (seventy-five years for a corporate copyright owner). In 1998 (as copyrights on works such as Disney’s Mickey Mouse were set to expire), Congress again extended the copyright period for an additional twenty years.

Today, nearly every innovation in digital culture creates new questions about copyright law. For example, is a video remix that samples copyrighted sounds and images a copyright violation or a creative accomplishment protected under the concept of fair use (the same standard that enables students to legally quote attributed text in their research papers)? One of the laws that tips the debates toward stricter enforcement of copyright is the Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998, which outlaws technology or actions that circumvent copyright systems.

In other words, it may be illegal merely to create or distribute technology that enables someone to make illegal copies of digital content, such as a movie DVD.

SOPA and PIPA

In general, the copyright lobby has enjoyed success getting lawmakers to pass favorable legislation. But this has not always been the case. Starting in 2011, U.S. lawmakers were considering two proposals: the Stop Online Piracy Act (SOPA) in the House, and the Protect Intellectual Property Act (PIPA) in the Senate. The proposals were spurred by concerns over illegally copied movies, music, games, and so on, that were being dubbed in foreign countries, outside the reach of U.S. law enforcement, and distributed globally via the Internet. Supporters said that PIPA and SOPA would attack the pirates by getting at the flow of pirated material online. But opponents saw it as an unprecedented power grab for Internet control by the U.S. government and raised cries of censorship and concerns about other ways the laws would threaten free speech. They argued that the laws would allow copyright holders to block Web sites, censor search results, and cut off advertising revenue without even going through a judge. Others feared the language was too vague and would reduce fair-use protections. Joining the protests were major Internet companies like Google, Mozilla, Wikipedia, and Reddit, who were among over 115,000 Web sites that held a “blackout” in protest on January 18, 2012. Wikipedia, for example, displayed a message to all visitors that said “Imagine a world without free knowledge” instead of the usual encyclopedic entries. The massive online protest resulted in three million e-mails to Congress to oppose the bills.8 The protests went international, with the European Union Parliament weighing in by adopting a resolution that stressed the “need to protect the integrity of the global internet and freedom of communication by refraining from unilateral measures to revoke IP addresses or domain names.”9

Although the SOPA and PIPA proposals have been dropped (at least for now), it’s notable that in addition to the important questions about free speech in a digital era, this conflict also represented a fight between “old” media and “new” media. The groups pushing for the bills were made up of people from the Motion Picture Association of America and the Recording Industry Association of America, whereas some of the highest-profile opponents were Internet groups like Wikipedia and Google. In addition to broader concerns over copyright versus free speech, the opposition effort probably got a boost from the public by portraying SOPA and PIPA as destructive to the more freewheeling and open culture of the Internet.

Libel

The biggest legal worry haunting editors and publishers today is the possibility of being sued for libel, a form of expression that, unlike political speech, is not protected under the First Amendment. Libel is defamation of someone’s character in written or broadcast form. It differs from slander, which is spoken defamation. Inherited from British common law, libel is generally defined as a false statement that holds a person up to public ridicule, contempt, or hatred, or that injures a person’s business or livelihood. Examples of potentially libelous statements include falsely accusing someone of professional incompetence (such as medical malpractice); falsely accusing a person of a crime (such as drug dealing); falsely stating that someone is mentally ill or engages in unacceptable behavior (such as public drunkenness); and falsely accusing a person of associating with a disreputable organization or cause (such as being a member of the Mafia or a neo-Nazi military group) (see “Media Literacy Case Study: A False Wikipedia ‘Biography’” on pages 444–445).

Since 1964, New York Times v. Sullivan has served as the standard for libel law. The case stems from a 1960 full-page advertisement placed in the New York Times by the Committee to Defend Martin Luther King and the Struggle for Freedom in the South. Without naming names, the ad criticized the law-enforcement tactics used in southern cities to break up Civil Rights demonstrations. The city commissioner of Montgomery, Alabama, L. B. Sullivan, sued the Times for libel, claiming the ad defamed him indirectly. Alabama civil courts awarded Sullivan $500,000, but the Times’ lawyers appealed to the Supreme Court. The Court reversed the ruling, holding that Alabama libel law violated the Times’ First Amendment rights.10

Private individuals (such as city sanitation employees, undercover police informants, or nurses) must prove three things to win a libel case: (1) that the public statement about them was false; (2) that damages or actual injury occurred (such as loss of a job or mental anguish); and (3) that the publisher or broadcaster was negligent in failing to determine the truthfulness of the statement.

In the Sullivan case, the Supreme Court asked future civil courts to distinguish whether plaintiffs in libel cases are “public officials” or “private individuals.” To win libel cases, the Court said, public officials (such as movie or sports stars, political leaders, or lawyers defending a prominent client) are held to a tougher standard and must prove falsehood, damages, negligence, and actual malice on the part of the news media. Actual malice means that the reporter or editor either knew the statement was false and printed or broadcast it anyway, or acted with a reckless disregard for the truth. Because actual malice against a public official is hard to prove, it is difficult for public figures to win libel suits.

Historically, the best defense against libel in American courts has been the truth. In most cases, if libel defendants can demonstrate that they printed or broadcast true statements, plaintiffs will not recover any damages—even if their reputations were harmed. There are other defenses against libel as well. For example, prosecutors (who would otherwise be vulnerable to accusations of libel) are granted absolute privilege in a court of law, so they can freely make accusatory statements toward defendants—a key part of their job. Reporters who print or broadcast statements made in court are also protected against libel.

Another defense against libel is the rule of opinion and fair comment, the notion that libel consists of intentional misstatements of factual information, not expressions of opinion. However, the line between fact and opinion is often blurry. For instance, one of the most famous tests of opinion and fair comment came with a case pitting conservative minister and political activist Jerry Falwell against Larry Flynt, publisher of Hustler, a pornographic magazine. The case developed after a spoof ad in the November 1983 issue of Hustler suggested that Falwell had had sex with his mother. Falwell sued for libel, demanding $45 million in damages. The jury rejected the libel suit but found that Flynt had intentionally caused Falwell emotional distress—and awarded Falwell $200,000. Flynt’s lawyers appealed, and the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the verdict in 1988, explaining that the magazine was entitled to constitutional protection.

Libel laws also protect satire, comedy, and opinions expressed in reviews of books, plays, movies, and restaurants. However, such laws do not protect malicious statements in which plaintiffs can prove that defendants used their free-speech rights to mount an uncalled-for, damaging personal attack.

Obscenity

For most of this nation’s history, legislators have argued that obscenity is not a form of expression protected by the First Amendment. However, experts have not been able to agree on what constitutes an obscene work, especially as definitions of obscenity have changed over the years. For example, during the 1930s, novels (such as James Joyce’s Ulysses) were judged obscene if they contained “four-letter words.”

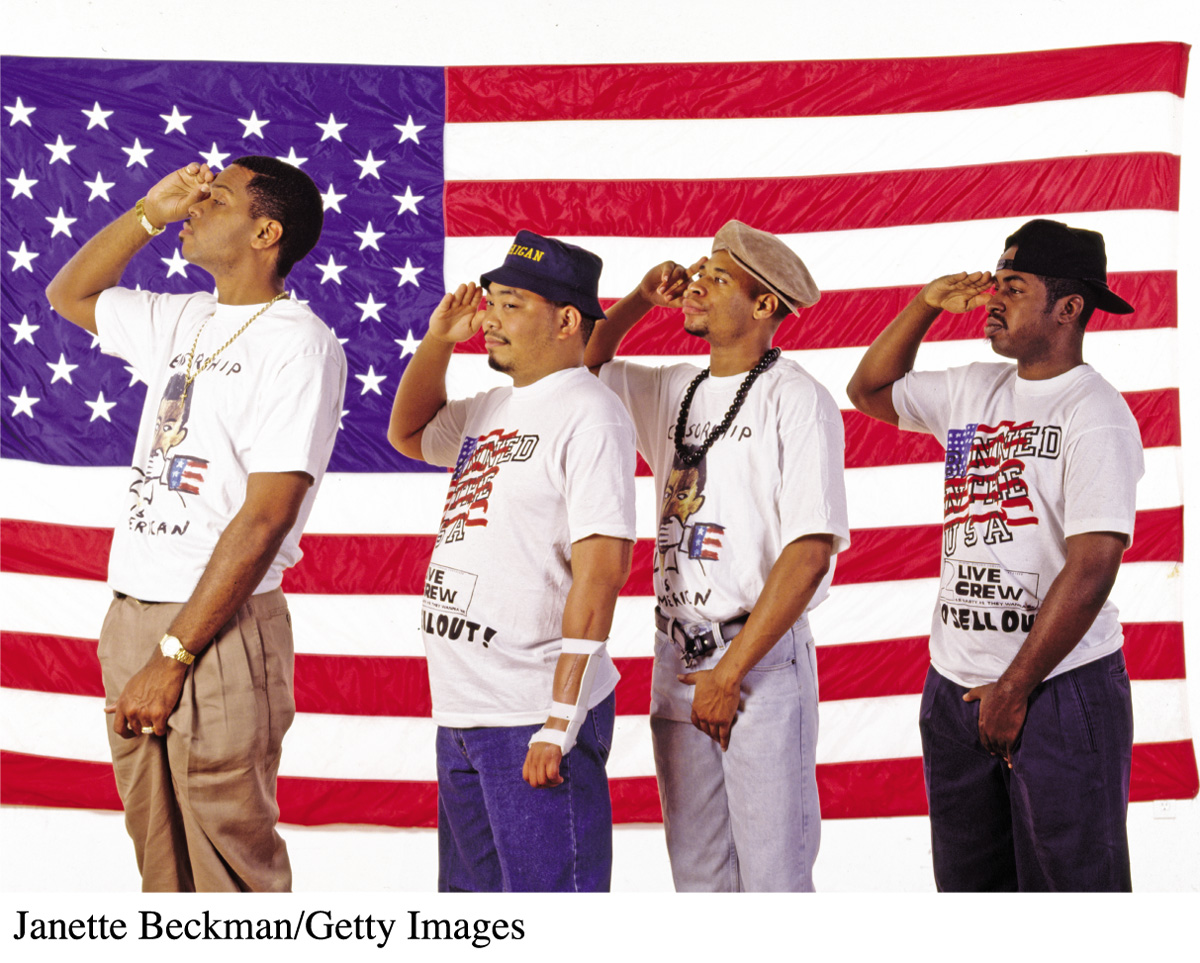

The current legal definition of obscenity, derived from the 1973 Miller v. California case, states that obscene materials meet three criteria: (1) the average person, applying contemporary community standards, finds that the material as a whole appeals to prurient interest (that is, incites lust); (2) the material depicts or describes sexual conduct in a patently offensive way; and (3) the material as a whole lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value. The Miller decision acknowledged that different communities and regions of the country have different standards with which to judge obscenity. It also required that a work be judged as a whole. This was designed to keep publishers from simply inserting a political essay or literary poem into pornographic materials to demonstrate that their publication contained redeeming features.

Since the Miller decision, major prosecutions of obscenity have been rare, and most battles now concern the Internet, for which the concept of community standards has been eclipsed by the medium’s global reach. The most recent incarnation of the Child Online Protection Act—originally conceived in 1998 to make it illegal to post “material that is harmful to minors”—was found unconstitutional in 2007 because it infringed on the right to free speech online. The presiding judge in this decision also stated that the act would be ineffective, as it wouldn’t apply to pornographic Web sites from overseas, which account for up to half of such sites. The ruling suggested that parents and software filters offer the best protection for children against harmful content on the Web.

Violation of Privacy Rights

Whereas libel laws safeguard a person’s character and reputation, the right to privacy protects an individual’s peace of mind and personal feelings. In the simplest terms, the right to privacy addresses a person’s right to be left alone, without his or her name, image, or daily activities becoming public property. The most common forms of privacy invasion are unauthorized tape recording, photographing, and wiretapping of someone; making someone’s personal records, such as health and phone records, available to the public; disclosing personal information, such as religious or sexual activities; and appropriating (without authorization) someone’s image or name for advertising or other commercial purposes.

In general, the news media have been granted wide protections under the First Amendment to do their work, even if it approaches or constitutes violation of privacy. For instance, journalists can typically use the names and pictures of private individuals and public figures without their consent in their news stories. Still, many local municipalities and states have passed “anti-paparazzi” laws protecting public individuals from unwarranted scrutiny and surveillance on their private property. A number of laws also protect regular citizens’ privacy. For example, the Privacy Act of 1974 protects individuals’ records from public disclosure unless they give written consent. In some cases, however, private citizens become public figures—for example, rape victims who are covered in the news. In these situations, reporters have been allowed to record these individuals’ quotes and use their images without permission.

The Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986 extended the law regarding private citizens to include computer-stored data and the Internet, such as employees’ e-mails composed and sent through their employer’s equipment. However, subsequent court decisions ruled that employees have no privacy rights in electronic communications conducted on their employer’s equipment. The USA PATRIOT Act of 2001 further weakened the earlier laws, giving the federal government more latitude in searching private citizens’ records and intercepting electronic communications without a court order. Following leaks from Edward Snowden about the domestic spying program of the NSA (National Security Agency), we learned that these interceptions and invasions of privacy were much more widespread than most people had guessed.

Congress took a step toward bringing more Internet privacy to Americans by proposing the Do Not Track Me Online Act of 2011. If passed, it would give consumers the ability to opt out of having their online activity collected by private companies without their permission. But in a society that is both fiercely defensive of its privacy and widely engaged in sharing more personal information than in any other period in history, it remains unclear how individual privacy will be legally controlled in the digital age.

First Amendment versus Sixth Amendment

First Amendment protections of speech and the press have often clashed with the Sixth Amendment, which guarantees an accused individual in “all criminal prosecutions … the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury.” Gag orders, shield laws, and laws governing the use of cameras in a courtroom all put restrictions on speech and other forms of expression for the sake of Sixth Amendment rights.

Bloggers and Legal Rights

Legal and journalism scholars discuss the legal rights and responsibilities of bloggers.

Discussion: What are some of the advantages and disadvantages to the audience turning to blogs, rather than traditional sources, for news?

Gag Orders

In recent criminal cases, some lawyers have used the news media to comment publicly on cases that are pending or in trial. This can make it difficult to assemble an impartial jury, thus threatening individuals’ Sixth Amendment rights. In the 1960s, the Supreme Court introduced safeguards for ensuring fair trials in heavily publicized cases. These included placing speech restrictions, or gag orders, on lawyers and witnesses. In some countries, courts have issued gag orders to prohibit the press from releasing information or giving commentary that might prejudice jury selection or cause an unfair trial. But in the United States, especially since a Supreme Court review in 1976, gag orders have been struck down as a prior-restraint violation of the First Amendment.

Shield Laws

Shield laws state that reporters do not have to reveal the sources of the information they use in news stories. The news media have argued that protecting sources’ confidentiality maintains reporters’ credibility, protects sources from possible retaliation, and serves the public interest by providing information citizens might not otherwise receive. Thirty-five states and the District of Columbia now have some type of shield law. However, there is no federal shield law in the United States, leaving journalists exposed to subpoenas from federal prosecutors and courts.

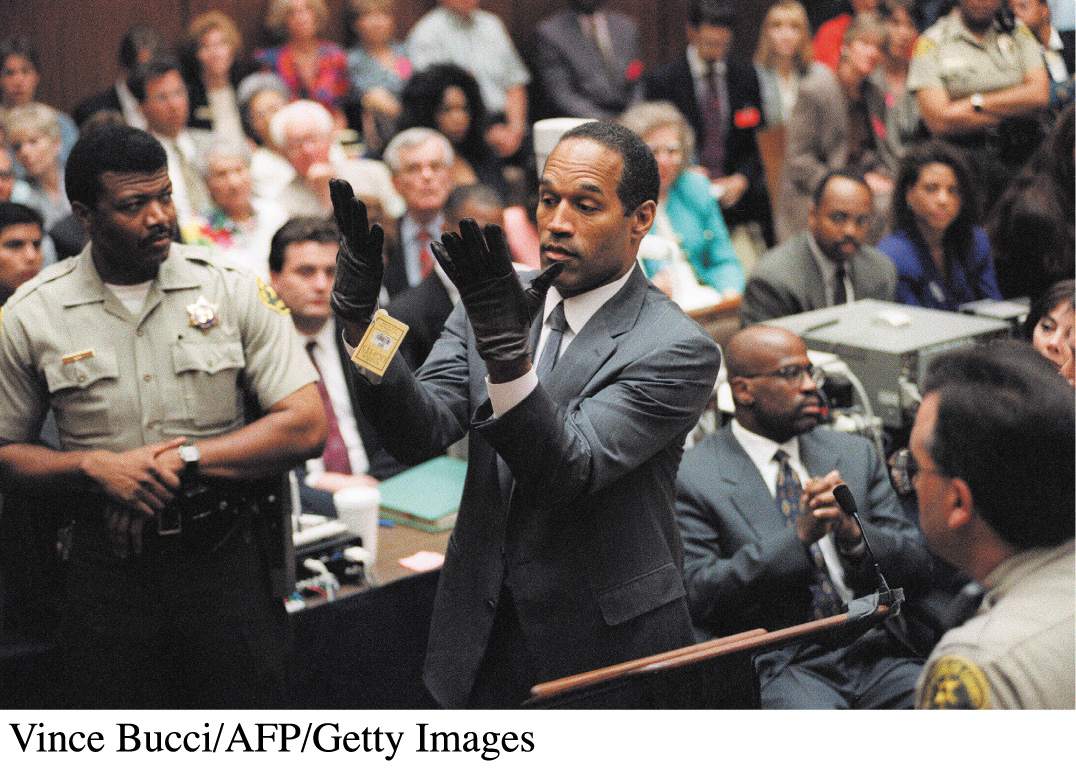

Laws Governing the Use of Cameras in a Courtroom

Debates over limiting electronic broadcast equipment and photographers in courtrooms date back to the Bruno Hauptmann trial in the mid-1930s. Hauptmann was convicted and executed for the kidnap-murder of the nineteen-month-old son of Anne and Charles Lindbergh (the aviation hero who made the first solo flight across the Atlantic Ocean in 1927). During the trial, Hauptmann and his attorney complained that the circus atmosphere fueled by the presence of radio and flash cameras prejudiced the jury and turned the public against him. After the trial, the American Bar Association amended its professional ethics code, stating that electronic equipment in the courtroom detracted “from the essential dignity of the proceedings.” For years after the Hauptmann trial, almost every state banned photographic, radio, and TV equipment from courtrooms.

But as broadcast equipment became more portable and less obtrusive, and as television became the major news source for most Americans, courts gradually reevaluated the bans. In the early 1980s, the Supreme Court ruled that the presence of TV equipment did not make fair trials impossible. The Court then left it up to each state to implement its own system. Today, all states allow television coverage of some cases (some just trial courts, some just appellate courts, some both), though most also allow presiding judges to place certain restrictions on coverage of courtrooms. The state courts are now dealing with questions about the use of other electronic devices, such as smartphones and tablets, and whether or not to allow reporters to tweet or send blog posts live from the courtroom. The United States Supreme Court continues to ban TV from its proceedings, although it broke its anti-radio rule in 2000 by permitting delayed broadcasts of the hearings on the Florida vote recount case that determined the winner of the 2000 presidential election.