The First Amendment, Broadcasting, and the Internet

As the film industry developed, the lack of clarity regarding the First Amendment’s protection of expression in movies prompted the industry to regulate itself. And with the rise of additional new media that our nation’s founders could not have envisioned—namely, broadcasting and the Internet—legislators and industry players once again began debating the question of how free these media are under the First Amendment. Different types of protections and levels of regulation developed in broadcast and cyberspace. Whereas film received protections similar to print in the 1952 Supreme Court ruling, broadcast is subject to fewer protections, and the Internet is so relatively new that people are still debating how First Amendment rights might apply to it.

Two Pivotal Court Cases

Drawing on the argument that limited broadcast signals constitute a scarce national resource, Congress passed the Communications Act of 1934 (see Chapter 6 on radio). The act mandated that radio broadcasters operate in “the public interest, convenience, or necessity,” suggesting that they were not free to air whatever they wanted. Since that time, station owners have challenged the “public interest” statute and argued that because the government is not allowed to dictate newspaper content, it similarly should not be permitted to control licenses or mandate broadcast programming. But the U.S. courts have outlined major differences between broadcast and print—as demonstrated by two cases.

The first case—Red Lion Broadcasting Co. v. FCC (1969)—began when WGCB, a small-town radio station in Red Lion, Pennsylvania, refused to give airtime to author Fred Cook. Cook wrote a book criticizing Barry Goldwater, the Republican Party’s presidential candidate in 1964. On a syndicated show WGCB aired, a conservative radio preacher and Goldwater fan verbally attacked Cook on the air. Cook asked for response time from the stations that carried the attack. Most complied, but WGCB snubbed him. He appealed to the FCC, which ordered the station to give Cook free time. The station refused, claiming the First Amendment gave it control over its programming content. The Supreme Court sided with the FCC and ordered the station to give Cook airtime, arguing that the public interest—in this case, the airing of differing viewpoints—outweighs a broadcaster’s rights.

The second case—Miami Herald Publishing Co. v. Tornillo (1974)—centered on the question of whether the newspaper in this case, the Miami Herald, should have been forced to give political candidate Pat Tornillo Jr. space to reply to an editorial opposing his candidacy. In contrast to the Red Lion decision, the Supreme Court sided with the paper. The Court argued that forcing a newspaper to give a candidate space violated the paper’s First Amendment right to decide what to publish. Clearly, print media had more freedom of expression than did broadcasting.

Dirty Words, Indecent Speech, and Hefty Fines

Like the Supreme Court’s rulings in the Red Lion and Miami Herald cases, regulators’ actions regarding indecency in broadcasting reflected the idea that broadcasters had less freedom of expression than did print media. In theory, communication law says that the government cannot censor (prohibit before the fact) broadcast content. However, the government may punish broadcasters after the fact for indecency.

Concerns over indecent broadcast programming cropped up in 1937, when the FCC scolded NBC for airing a sketch featuring sultry comedian-actress Mae West. After the sketch, which West peppered with sexual innuendos, the networks banned her from further radio appearances for “indecent” speech. Since then, the FCC has periodically fined or reprimanded stations for indecent programming, especially during times when children might be listening. For example, after an FCC investigation in the 1970s, several stations lost their licenses or were fined for broadcasting topless radio, which featured deejays and callers discussing intimate sexual subjects in the afternoon. (Topless radio would reemerge in the 1980s, this time with doctors and therapists, rather than deejays, offering intimate counsel to listeners.)

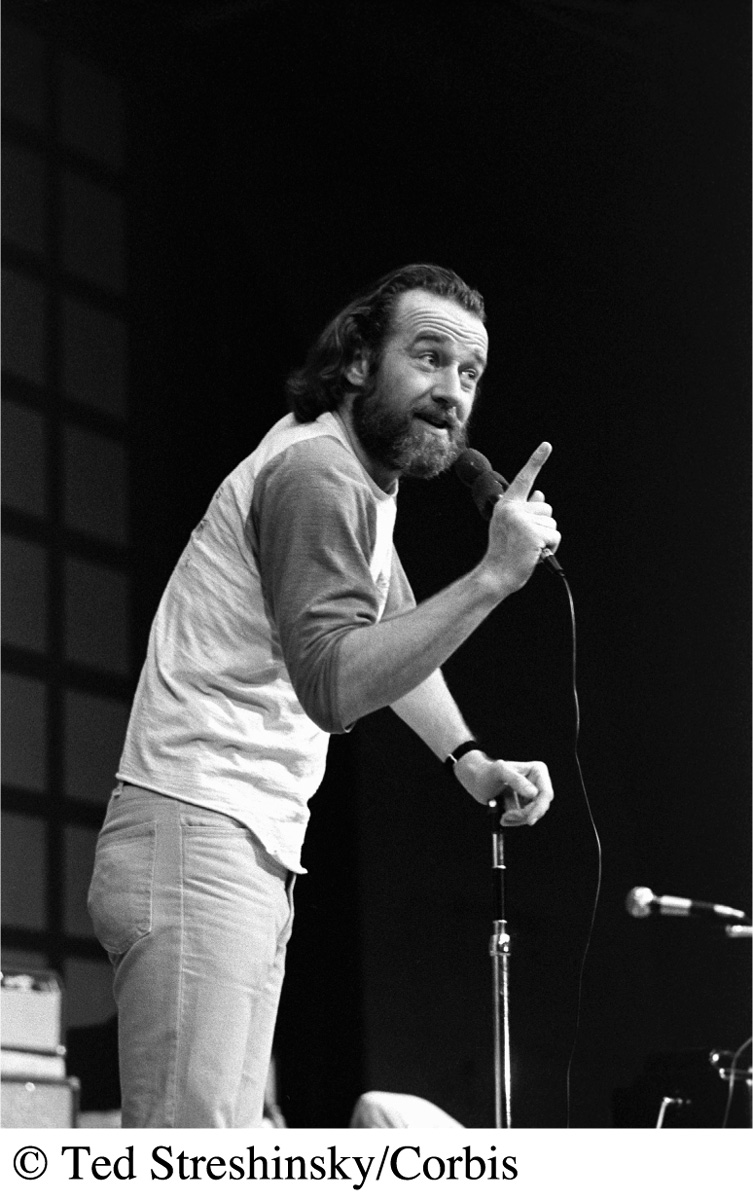

The current precedent for regulating broadcast indecency stems from a complaint to the FCC that came in 1973. In the middle of the afternoon, WBAI, a nonprofit Pacifica network station in New York, aired George Carlin’s famous comedy sketch about the “seven dirty words” that can’t be said on TV. A man riding in a car with his fifteen-year-old son heard the program and complained to the FCC, which sent WBAI a letter of reprimand. Although no fine was issued, the station challenged the warning on principle—and won its case in court. The FCC promptly appealed to the Supreme Court. Though no court had legally defined indecency (which remains undefined today), the Supreme Court sided with the FCC in the 1978 FCC v. Pacifica Foundation case. The decision upheld the FCC’s authority to require broadcasters to air adult programming only at times when children were not likely to be listening. The FCC banned indecent programs from most stations between 6:00 A.M. and 10:00 P.M.

Political Broadcasts and Equal Opportunity

In addition to indecency rules, another law affecting broadcasting but not the print media is Section 315 of the Communications Act of 1934. The section mandates that during elections, broadcast stations must provide equal opportunities and response time for qualified political candidates. In other words, if broadcasters give or sell time to one candidate, they must give or sell the same opportunity to others. Local broadcasters and networks have fought this law for years, claiming that because no similar rule applies to newspapers or magazines, the law violates their First Amendment right to control content. Many stations decided to avoid political programming entirely, ironically reversing the rule’s original intention. The TV networks managed to get the law amended in 1959 to exempt newscasts, press conferences, and other events—such as political debates—that qualify as news. For instance, if a senator running for office appears in a news story, opposing candidates cannot invoke Section 315 and demand free time.

Supporters of the equal opportunity law in broadcasting argue that it enables lesser-known candidates representing views counter to those of the Democratic and Republican parties to add their perspectives to political dialogue. It also gives less-wealthy candidates a more affordable channel than newspaper and magazine ads for getting their message out to the public.

Fair Coverage of Controversial Issues

Considered an important corollary to Section 315, the Fairness Doctrine was to controversial issues what Section 315 is to political speech. Initiated in 1949, this FCC rule required stations to air programs about controversial issues affecting their communities and to provide competing points of view during the programs. Broadcasters again protested that the print media did not have to obey these requirements. And once more, many stations simply avoided airing controversial issues. The Fairness Doctrine ended with little public debate in 1987 after a federal court ruled that it was merely a regulation, not an extension of Section 315 law.

Since 1987, however, support for reviving the Fairness Doctrine has surfaced periodically. Its advocates argue that broadcasting is fundamentally different from—and more pervasive than—print media. Thus, it should be more accountable to the public interest. The end of the Fairness Doctrine might have contributed to a more polarized political climate, fed in part by news networks unburdened by the requirement to provide different points of view. On the other hand, the lack of requirement could allow the dissemination of other views that might not otherwise garner much attention.

Communication Policy and the Internet

Because the Internet is not regulated by the government, is not subject to the Communications Act of 1934, and has done little self-regulating, many people see it as the one true venue for unlimited free speech under the First Amendment. Its current global expansion is comparable to the early days of broadcasting, when economic and technological growth outstripped law and regulation.

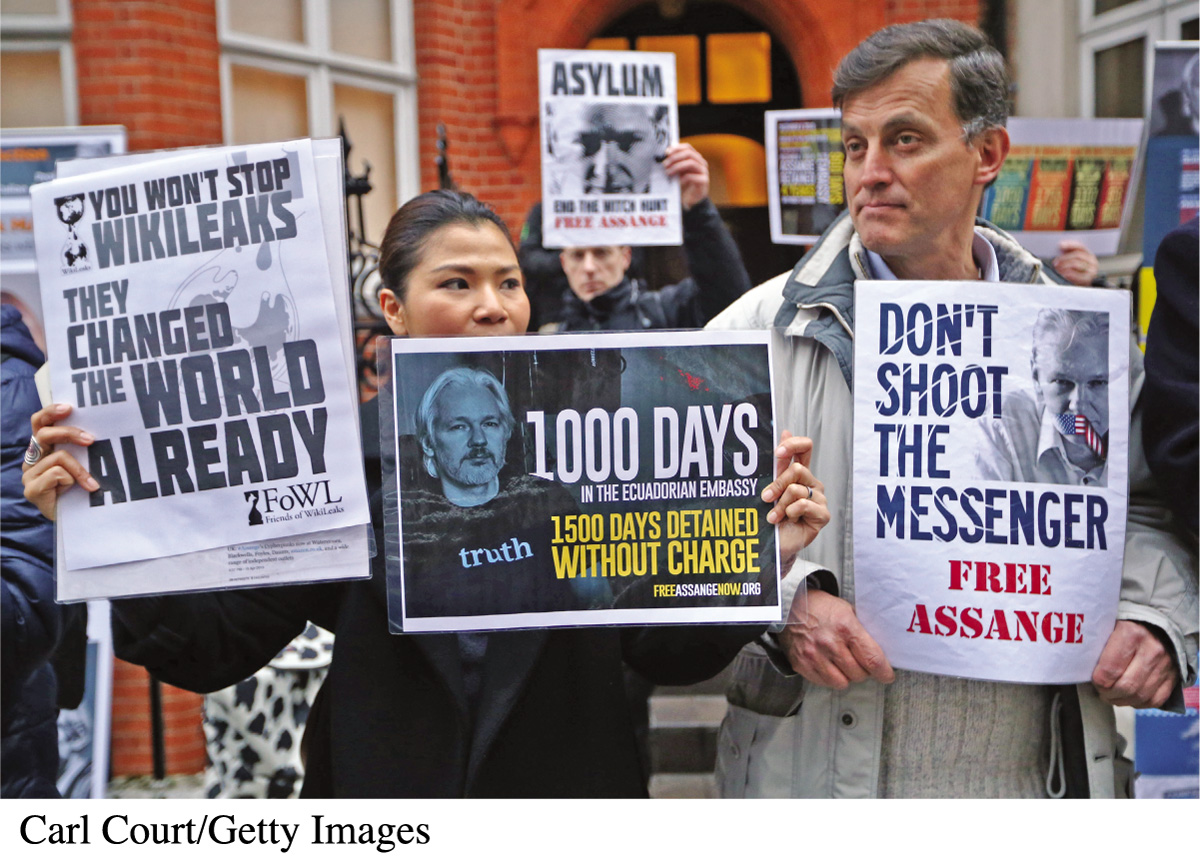

Early debates about what forms of expression should be allowed on the Internet typically revolved around such issues as civility and pornography. Those discussions have continued (see “Converging Media Case Study: Bullying Converges Online” on pages 458–459), but the debate has expanded to issues like government surveillance and how traditional means like wiretapping and search warrants can be expanded to include the turning over of Internet browsing histories and other data. As this medium continues to expand rapidly, we will need to consider some important questions: Will the Internet remain free of government attempts to contain it, change it, and monitor who has access to it? Can the Internet continue to serve as a democratic forum for regional, national, and global interest groups? Many global movements use this medium to fight political oppression. Human Rights Watch, for example, encourages free-expression advocates to use blogs “for disseminating information about, and ending, human rights abuses around the world.” 12