Chapter Introduction

14

Media Economics and the Global Marketplace

Some of today’s biggest mass media players have long histories, which they’ve built on and adapted through various technological changes, including history’s recent digital turn. Columbia Records (now part of the Sony empire) was founded in 1888. The Warner Brothers piece of the current Time Warner conglomerate got its start in 1903, when three brothers bought their first movie theater. Walt Disney Studios began in the back of a small L.A. real estate office in 1923. NBC started out in 1926 as a radio network formed by RCA (founded in 1919) and is currently part of NBC Universal, which is a subsidiary of cable and broadband giant Comcast. Comcast itself started out with just over one thousand cable subscribers in 1963. There can be big advantages to having the resources, name recognition, and established political connections that come with being a longtime member of the mass media. But in the age of the Internet and the Internet start-up, the explosive growth of a new media business can happen at a breathtaking pace. Two prime examples of this are Google and YouTube.

Google traces its origins to 1995, when Stanford student Sergey Brin was assigned to show prospective student Larry Page around campus. A year later the pair were collaborating on a prototype search engine, and in 1997 they registered the domain name “Google.com,” a play on the mathematical word googol (the number written out as a one followed by a hundred zeros). In 1998, the pair officially registered the company as an entity and hired their first employee. The company proceeded to grow at a startling pace, adding more and more services and features every few months—including AdWords in 2000, Images in 2001, Froogle (now Google Shopping) in 2002, Gmail in 2004, and Google Maps and a mobile search app in 2005—soon becoming one of the top American media companies1 (see also Table 14.1).

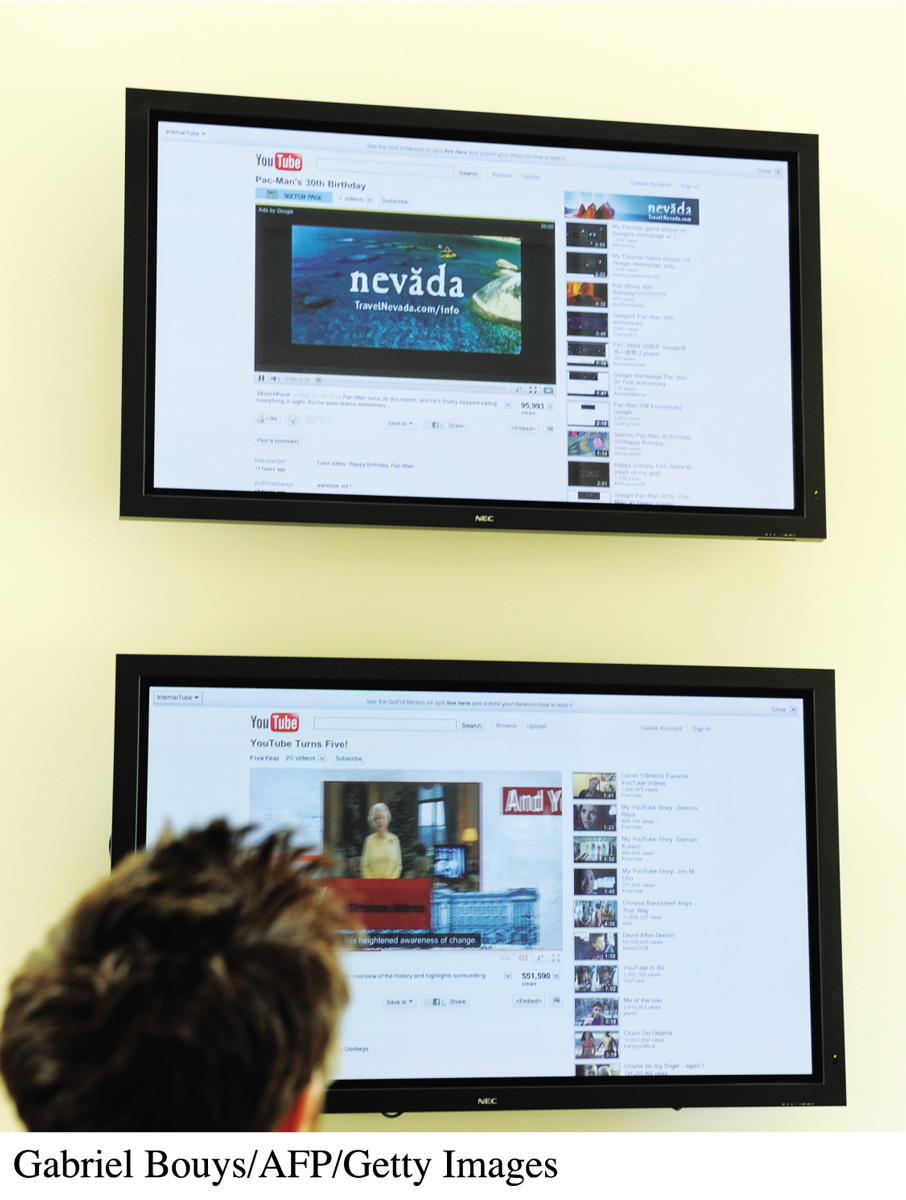

If anything, YouTube is even more of a digital age success story. The three founders, Chad Hurley, Steve Chen, and Jawed Karim, say they got the idea for a video-sharing site during a dinner party, and on Valentine’s Day 2005 they registered the trademark, name, and logo for YouTube. The first video (of Karim at the zoo) was posted on April 23, and by September the site got its first million-hit video (a Nike ad). By December, the company was getting major investment attention, and the site was more widely available after upgrading bandwidth and servers. Google bought YouTube in October 2006, a little more than a year after the first video was posted, for $1.65 billion. Since then, YouTube has been run as a subsidiary of Google and continues to grow in popularity. The economic impact of a video-sharing and social media site like YouTube goes well beyond the video and banner ads it can sell. The site has launched dozens of homegrown stars (including Ryan Higa, Jenna Marbles, and Pewdie Pie) and has become a source for breaking news (such as the posts of mobile phone videos that have been the basis for news stories about police abuse).

The logistics of the rise of digital conglomerates like Google and YouTube may be different from those of traditional mass media companies like Sony or Disney, especially in their speed. But their enormous flow of money and substantial power over the media landscape make the economics of these relative newcomers just as important when studying the media.

COMPARING GOOGLE TO TIME WARNER AND DISNEY, WE SEE TWO TYPES OF MEDIA SUCCESS, one based on an idea that could have happened only in the Internet age (a need for a better search engine), and the other, legacy entertainment conglomerates that have survived years of leadership changes and power struggles to enter the twenty-first century with massive resources. But not all of the mergers, takeovers, and acquisitions that have swept through the global media industries in the last twenty years have capitalized on the histories and reputations of the corporations involved. Take, for instance, the ill-timed purchase of MySpace by News Corp. in 2005. Paying $580 million for what was then the world’s most popular social media site, Rupert Murdoch would watch a newcomer named Mark Zuckerberg (and his site Facebook) reduce the value of MySpace to $35 million, the price Justin Timberlake and Specific Media, Inc., paid for the service in 2011. Despite such spectacular exceptions, many cases of ownership convergence have provided even more economic benefit to the massive multinational corporations that dominate the current media landscape. As a consequence, we currently find ourselves enmeshed and implicated in an immense media economy characterized by consolidation of power and corporate ownership in just a few hands. This phenomenon, combined with the advent of the Internet, has made our modern media world markedly distinct from that of earlier generations—at least in economic terms. Not only has a handful of media giants—from Time Warner to Google—emerged, but the Internet has permanently transformed the media landscape. The Internet has dried up newspapers’ classified-ad revenues; altered the way music, movies, and TV programs get distributed and exhibited; and forced almost all media businesses to rethink the content they will provide—and how they will provide it.

In this chapter, we explore the developments and tensions shaping this brave new world of mass media by:

examining the transition our nation has made from a manufacturing to an information economy by considering how the media industries’ structures have evolved, the impact of deregulation, the rise of media powerhouses through consolidation, trends that shape and reshape media industries, and theories about why U.S. citizens tend not to speak up about the dark side of mass media

analyzing today’s media economy, including how media organizations make money and formulate strategies, and how the Internet has changed the rules of the media game

assessing the specialization and use of synergy currently characterizing media, using the history of the Walt Disney Company as an example

taking stock of the social challenges the new media economy has raised, such as subversion of antitrust laws, consumers’ loss of control in the marketplace, and American culture’s infiltration into other cultures

evaluating the media marketplace’s role in our democracy by considering such questions as whether consolidation of media hurts or helps democracy, and what impact recent media-reform movements might have