The Transition to an Information Economy

In the first half of the twentieth century, the U.S. economy was built on mass production, the proliferation of manufacturing plants, and intense rivalry with businesses in other nations. By midcentury, this manufacturing-based economy began transitioning into an economy fueled by information (which new technologies made easier to generate and exchange anywhere) and by cooperation with other economies. Offices displaced factories as major work sites; centralized mass production declined in the United States and other developed nations; and American firms began outsourcing manufacturing work to developing countries, where labor was cheap and environmental standards were lax.

Mass media industries seized the opportunity to expand globally. They began marketing music, movies, television programs, and computer software overseas. And the media mergers-and-acquisitions (M&A) drive that had begun in the United States in the 1960s expanded into global media consolidation by the 1980s.

This transition from a manufacturing-based to an information-based economy had several defining points: Early regulation designed to break up monopolies in manufacturing-related industries such as oil, railroads, and steel gave way to deregulation, which ultimately catalyzed the M&A drive that created media powerhouses. These information-based corporations in turn fueled new trends in the industry (including a decline of unionized labor and a growing wage gap). Soon a new society took shape—one in which the biggest media companies defined the values that dominated culture not only in the United States but also around the globe.

CHAPTER 14 // TIMELINE

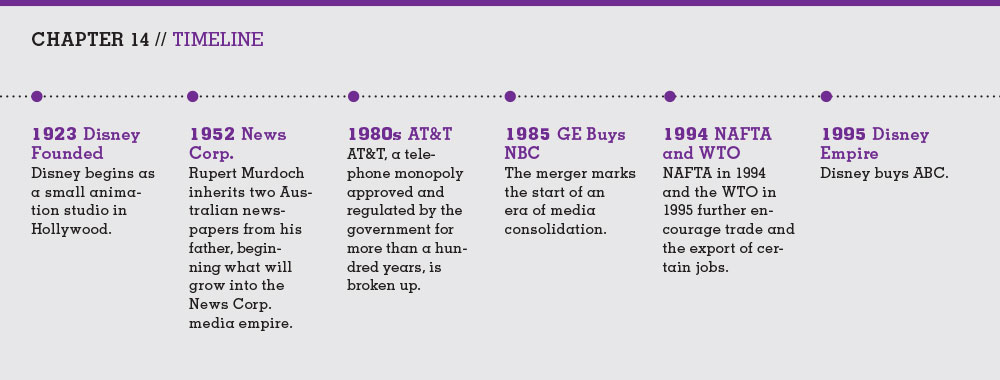

1923 Disney Founded

Disney begins as a small animation studio in Hollywood.

1952 News Corp.

Rupert Murdoch inherits two Australian newspapers from his father, begin-ning what will grow into the News Corp. media empire.

1980s AT&T

AT&T, a tele-phone monopoly approved and regulated by the government for more than a hundred years, is broken up.

1985 GE Buys NBC

The merger marks the start of an era of media consolidation.

1994 NAFTA and WTO

NAFTA in 1994 and the WTO in 1995 further encourage trade and the export of certain jobs.

1995 Disney Empire

Disney buys ABC.

1996 Time Warner

The company buys Turner Broadcasting.

1996 Media Merger

The Telecommunications Act of 1996 unleashes a wave of media mergers.

2001 AOL and Time Warner

AOL, the largest Internet service provider at the time, merges with Time Warner, the largest media corporation.

2009 More Cable Deregulation

A U.S. federal court strikes down the FCC’s regulation limiting a cable company’s holdings to not more than 30 percent of the U.S. cable market.

2011 Comcast Buys NBC

Cable giant Comcast completes a deal to buy a majority share of NBC Universal.

Click on the timeline above to see the full, expanded version.

How Media Industries Are Structured

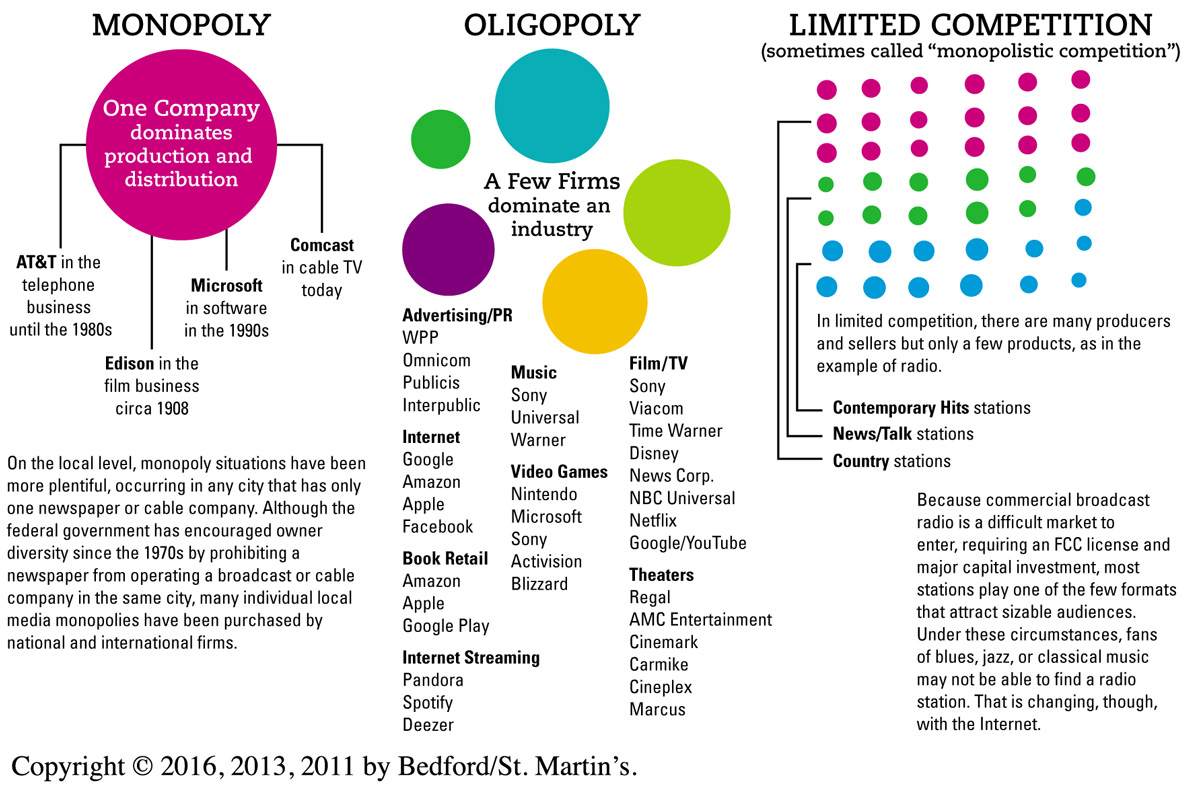

Most industries that make up the media economy have one of three common structures: monopoly, oligopoly, and limited competition.

Monopoly

A monopoly arises when a single firm dominates production and distribution in a particular industry—nationally or locally. For example, at the national level, AT&T ran a rare government-approved and government-regulated monopoly—the telephone business—for more than a hundred years before the government broke it up in the mid-1980s. And Microsoft dominates the worldwide market for business computer operating systems.

On the local level, monopolies have proved more plentiful, arising in any city that has only one newspaper or one cable company. The federal government has encouraged owner diversity since the 1970s by prohibiting a newspaper from operating a broadcast or cable company in the same city. But since 2003, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) has made several efforts to relax cross-ownership rules, arguing that the Internet and cable and satellite television provide sufficient informational diversity for citizens. Media activists have countered that the large traditional media are still the dominant news media in any market, and that when they merge, it results in fewer independent media voices.

Oligopoly

In an oligopoly, just a few firms dominate an industry. For example, in the late 1980s, the production and distribution of the world’s music was controlled by only six corporations. By 2004, after a series of acquisitions, the “big six” had been reduced to the “big four”—Time Warner (U.S.), Sony (Japan), Universal (France), and EMI (Great Britain). In late 2011, Universal purchased EMI at auction, and by 2012 three companies controlled nearly two-thirds of the recording industry market. The Internet is also changing the music game, enabling companies like Apple to gain new dominance with innovative business models such as the iTunes store. Time will reveal whether the “big three” maintain their status as an oligopoly.

Firms that make up an oligopoly face little economic competition from small independent firms. However, many oligopolies choose to purchase independent companies in order to nurture the fresh ideas and products those companies generate. Without the financial backing of an oligopoly, many of those ideas and products could have a tough time making it to market.

Limited Competition

Limited competition characterizes a media market that has many producers and sellers but only a few products within a particular category.2 For instance, hundreds of independently owned radio stations operate in the United States. However, most of these commercial stations feature just a few formats—such as country, classic rock, news/talk, or contemporary hits. Fans of other formats—including blues, alternative country, and classical music—may not be able to find a radio station that matches their interests. Of course, as with music, the Internet is changing radio, too, enabling companies like Pandora and Spotify to offer streaming audio for a huge array of formats.

Deregulation Trumps Regulation

Beginning in the early twentieth century, Congress passed several acts intended to break up corporate trusts and monopolies, which often fixed prices to force competitors out of business. But later in the century, many business leaders began complaining that such regulation was restricting the flow of capital essential for funding business activities. President Jimmy Carter (1977–1981) initiated deregulation, and President Ronald Reagan (1981–1989) dramatically weakened most controls on business (e.g., environmental and worker safety rules). Many corporations in a wide range of industries flourished in this new pro-commerce climate. Deregulation also made it easier for companies to merge, to diversify, and—in industries such as the airlines, energy, communications, and financial services—to form oligopolies.3

In the broadcast industry, the Telecommunications Act of 1996 (under President Bill Clinton) lifted most restrictions on how many radio and TV stations one corporation could own. The act further permitted regional telephone companies to buy cable firms. In addition, cable operators regained the right to raise their rates with less oversight and to compete in the local telephone business. What prompted this shift to deregulation in the communications industry? With new cable channels, DBS, and the Internet, lawmakers no longer saw broadcasting as a scarce resource—once a major rationale for regulation as well as government funding of noncommercial and educational stations.

Not surprisingly, the 1996 act unleashed a wave of mergers in the industry, as television, radio, cable, telephone, and Internet companies fought to become the biggest corporations in their business sector and acquire new subsidiaries in other media sectors. The act also revealed legislators’ growing openness to make special exemptions for communications companies. For example, in 1995, despite complaints from NBC, News Corp. received a special dispensation from the FCC and Congress that allowed it to continue owning and operating the Fox network and a number of local TV stations.

Today, regulation of the communications industry is even looser. In late 2007, the FCC relaxed its rules further when it said that a company located in a Top 20 market (ranging in size from New York to Orlando, Florida) could own one TV station and one newspaper as long as there were at least eight TV stations in that market. Previously, a company could not own a newspaper and a broadcast outlet (a TV or radio station) in the same market. In 2009, a U.S. federal court struck down the FCC’s regulation limiting a cable company’s holdings to not more than 30 percent of the U.S. cable market, opening the possibility for a new round of unlimited cable mergers and acquisitions.

The Rise of Media Powerhouses

Into the 1980s, antitrust rules attempted to ensure diversity of ownership among competing businesses. In the mid-1980s, for instance, the Justice Department broke up AT&T’s century-old monopoly, creating competition in the telephone industry. But as politicians eroded those laws, the overall result has been much more consolidation and much less competition in the world of mass media.

Not only were some rules relaxed, but the antitrust laws have been unevenly applied in media industries, forcing competition in some industries while allowing consolidation in others. For example, as the Justice Department broke up AT&T to create competition in the telephone industry, it also authorized several mass media mergers that concentrated power in the hands of a few behemoths. These included General Electric’s purchase of RCA/NBC in the 1980s, Disney’s acquisition of ABC for $19 billion in 1995, and Time Warner’s purchase of Turner Broadcasting for $7.5 billion in 1996. In 2001, AOL acquired Time Warner for $106 billion—the largest media merger in history at the time. In 2011, cable giant Comcast purchased a majority share of NBC Universal, once the deal was approved by regulatory agencies.

As traditional mass media corporations have grown, we’ve also seen the rise of new media powerhouses in the twenty-first century. Companies like Apple, Google, Amazon, and Facebook aren’t experts at creating media programming, but they’ve envisioned new ways for us to experience media content: by buying content from their retail stores (e.g., the iTunes store and Amazon.com), consuming content on their innovative devices (e.g., the iPad, the Kindle Fire, the Android mobile phone), and being linked to other media content (via Google search and our friends on Facebook). Imagine experiencing the mass media without using a product or service of one of these companies and you begin to understand how this “digital turn,” with these four companies leading the way, has transformed the mass communication environment in less than a decade (see “Converging Media Case Study: Shifting Economics” on pages 476–477).

The Impact of Media Ownership

Media critics and professionals debate the pros and cons of media conglomerates.

Discussion: This video argues that it is the drive for bottom-line profits that leads to conglomerates. What solution(s) might you suggest to make the media system work better?