Specialization and Global Markets

The outsourcing and offshoring of many jobs and the breakdown of global economic borders were bolstered by trade agreements made among national governments in the mid-twentieth century. These included NAFTA (North American Free Trade Agreement) in 1994 and the WTO (World Trade Organization) in 1995. Such agreements enabled the emergence of transnational media corporations and stimulated business deals across national borders. Technology helped, too, making it possible for consumers around the world to easily swap music, TV shows, and movies on the Internet (legally and illegally). All of this has in turn accelerated the global spread of media products and cultural messages.

As globalization gathered momentum, companies began specializing to enter the new, narrow markets opening up to them in other countries. They also began seeking ways to step up their growth through synergies—opportunities to market different versions of a media product.

The Rise of Specialization and Synergy

As globalization picked up speed, several mass media—namely, the magazine, radio, and cable industries—sought to tap specialized markets in the United States and overseas, in part to counter television’s mass appeal. For example, cable channels such as Nickelodeon and the Disney Channel serve the under-eighteen market, History draws older viewers, Lifetime and Bravo go after women, and BET targets young African Americans.

In addition to specialization, media companies sought to spur growth through synergy—the promotion and sale of different versions of a media product across a media conglomerate’s various subsidiaries. An example of synergy is Time Warner’s HBO cable special about “the making of” a Warner Brothers movie reviewed in Time magazine. Another example is Sony’s buying up movie studios and record labels and playing their content on its electronic devices (which are often prominently displayed in their movies). But of all the media conglomerates, the Walt Disney Company perhaps best exemplifies the power of both specialization and synergy.

Disney: A Postmodern Media Conglomerate

After Walt Disney’s first cartoon company, Laugh-O-Gram, went bankrupt in 1922, Disney moved to Hollywood and found his niche. He created Mickey Mouse (originally named Mortimer) for the first sound cartoons in the late 1920s. He later began development on the first feature-length cartoon, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, which he completed in 1937.

For much of the twentieth century, the Disney Company set the standard for popular cartoons and children’s culture. Nonetheless, the studio barely broke even because cartoon projects took time (four years for Snow White) and commanded the company’s full array of resources. Moreover, the market for the cartoon film shorts that Disney specialized in was drying up, as fewer movie theaters were showing the shorts before their feature films.

Driving to Diversify

With the demise of the cartoon film short in movie theaters, Disney expanded into other specialized areas. The company’s first nature documentary short, Seal Island, came in 1949; its first live-action feature, Treasure Island, in 1950; and its first feature documentary, The Living Desert, in 1953. Also in 1953, Disney started Buena Vista, a distribution company. This was the first step in the studio’s becoming a major player in the film industry.

Disney also counted among the first film studios to embrace television. In 1954, the company launched a long-running prime-time show, and television became an even more popular venue than theaters for displaying Disney products. Then, in 1955, the firm added another entirely new dimension to its operations: It opened its Disneyland theme park in Southern California. (Walt Disney World in Orlando, Florida, would begin operation in 1971.) Eventually, Disney’s theme parks would produce the bulk of the company’s revenues.

Capturing Synergies

Walt Disney’s death in 1966 triggered a period of decline for the studio. But in 1984, a new management team, led by Michael Eisner, initiated a turnaround. The company’s newly created Touchstone movie division reinvented the live-action/animation hybrid for adults and children in Who Framed Roger Rabbit? (1988). A string of hand-drawn animated hits followed, including The Little Mermaid (1989) and Beauty and the Beast (1991). In a rocky partnership with Pixar Animation Studios, Disney also distributed a series of computer-animated blockbusters, including Toy Story (1995) and Finding Nemo (2003).

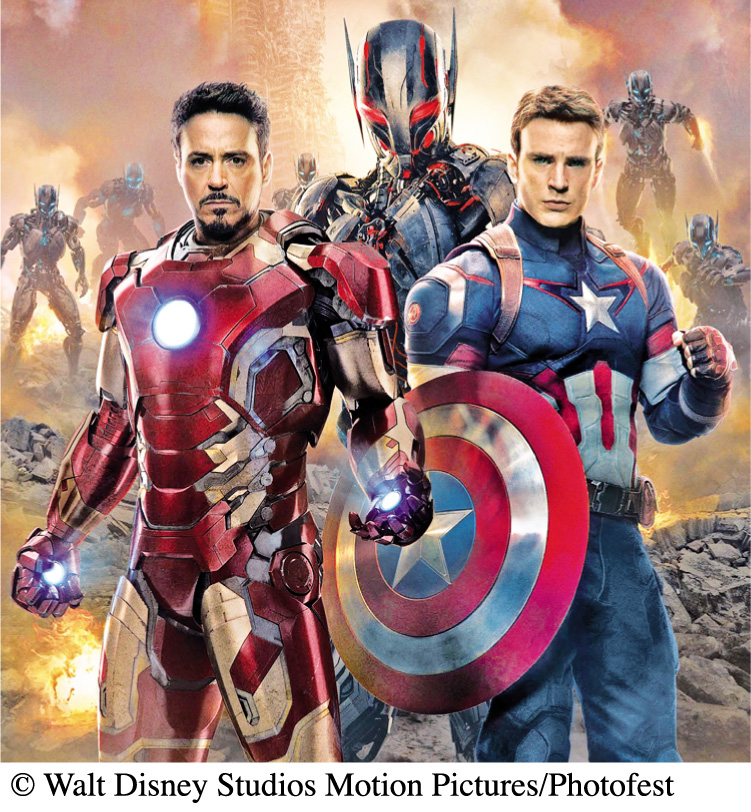

Since then, Disney has come to epitomize the synergistic possibilities of media consolidation. It can produce an animated feature or regular film for theatrical release and DVD distribution. Characters and stories from blockbuster films like The Avengers, Thor, and the Iron Man franchises can become series on the network ABC (Disney owns Marvel and ABC), like the programs Agents of SHIELD and Agent Carter, with storylines that intersect with the movies. Disney can release a book version of a movie through its publishing arm, Hyperion, and air “the-making-of” versions on cable’s Disney Channel or ABC Family. It can also publish stories about the movie’s characters in Disney Adventures, the company’s popular children’s magazine. Indeed, characters have become attractions at Disney’s theme parks, which themselves have spawned lucrative Hollywood blockbusters, like the Pirates of the Caribbean series. Some Disney films have had as many as seventeen thousand licensed products—from clothing to toys to dog food bowls. And in New York City, Disney even renovated several theaters and launched versions of Mary Poppins, The Lion King, and Aladdin as successful Broadway musicals.

Expanding Globally

Building on the international appeal of its cartoon features, Disney extended its global reach by opening a successful theme park in Japan in 1983. Three years later, the company started marketing cartoons to Chinese television—attracting an estimated 300 million viewers per week. Disney also launched a magazine in Chinese and opened several Disney stores and a theme park in Hong Kong. Disney continued its international expansion in the 1990s with the opening of EuroDisney (now called Disneyland Paris). In 1997, Orbit—a Saudi-owned satellite relay station based in Rome—introduced Disney’s twenty-four-hour cable channel to twenty-three countries in the Middle East and North Africa. Disney also expanded its products globally, adding a fourth ship to its international cruise line and a new nationwide Disney channel in Russia, and starting construction on the Shanghai Disney Resort in China, scheduled for a 2015 opening.

Facing Challenges and Seizing Opportunities

From 2000 to 2003, Disney grew into the world’s second-largest media conglomerate. Yet the cartoon pioneer encountered major challenges as well as new opportunities presented by the digital age. Challenges included a recession, failed films and Internet ventures, declining theme-park attendance, and damaged relationships with a number of partners and subsidiaries (including Pixar and Miramax).

By 2005, Disney had fallen to No. 5 among movie studios in U.S. box-office sales—down from No. 1 in 2003. A divided and unhappy board of directors forced Eisner out in 2005, after he had served twenty-one years as CEO.7 The following year, new CEO Robert Iger repaired the relationship between Disney and Pixar: He merged the companies and made Steve Jobs, founder of Pixar and Apple Computer, a Disney board member.

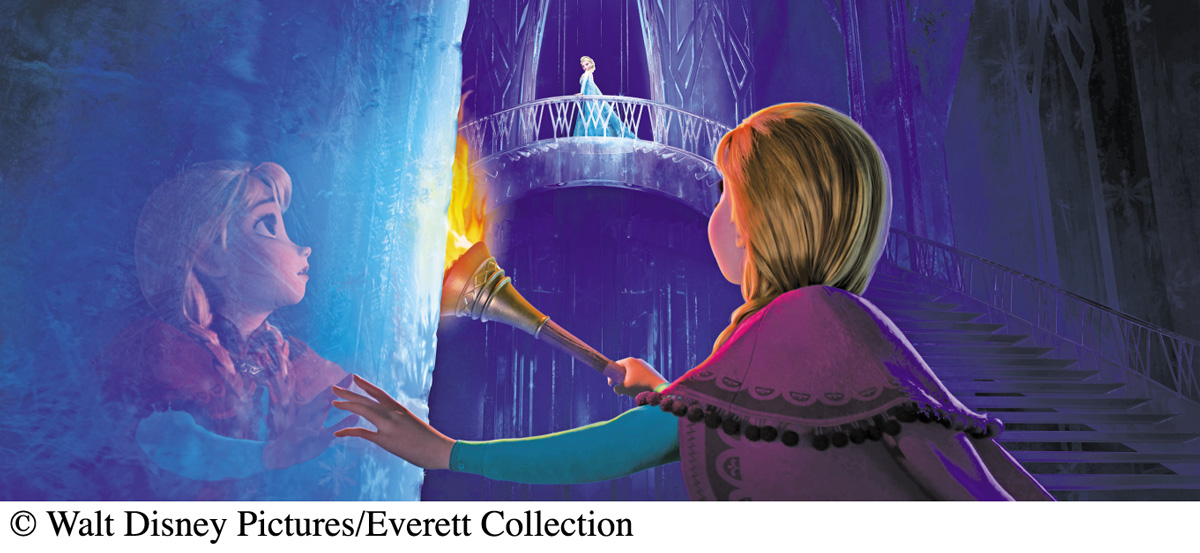

The Pixar deal showed that Disney was ready to seize the opportunities presented by the digital age. The company decided to focus on television, movies, and its new online initiatives. To that end, it sold its twenty-two radio stations and the ABC Radio Network to Citadel Broadcasting for $2.7 billion in 2007. Disney also made its movies and TV programs (and ABC’s content) available for download at Apple’s iTunes store, revamped its Web site as an entertainment portal, and joined News Corp. and NBC Universal as a partner in the video-streaming site Hulu.com in 2009. Disney made another big investment that year by purchasing Marvel Entertainment for $4 billion, which brought Spider-Man, Iron Man, the X-Men, and other superheroes into the Disney pool of characters, providing additional financial assets even when its other projects—such as underperforming movies Mars Needs Moms and John Carter—grossed less than anticipated. Disney mourned the death of Steve Jobs in 2011 but continued producing animated movies from Pixar and its in-house studios, scoring an enormous Marvel-branded hit with The Avengers in 2012, followed by more hit films based on Marvel characters, and then the animated hit Frozen in late 2013. In 2012, Disney purchased Lucasfilm and, with it, the rights to the Star Wars and Indiana Jones movies and characters; a new Star Wars film, The Force Awakens, followed in 2015. This means that Disney now has access to whole casts of “new” characters—not just for TV programs, feature films, and animated movies but also for its multiple theme parks.

The Growth of Global Audiences

As Disney’s story shows, international expansion has afforded media conglomerates key advantages, including access to profitable secondary markets and opportunities to advance and leverage technological innovations. As media technologies have become cheaper and more portable (from the original Walkman to the iPad), American media have proliferated both inside and outside U.S. boundaries.

Today, greatly facilitated by the Internet, media products easily flow into the eyes and ears of people around the world. And thanks to satellite transmission, North American and European television is now available at the global level. Cable services such as CNN and MTV have taken their national acts to the international stage, delivering their content to more than two hundred countries.

This growth of global audiences has permitted companies that lose money on products at home to profit in overseas markets. Roughly 80 percent of American movies, for instance, do not earn back their costs in U.S. theaters; they depend on foreign circulation as well as home-video formats to make up for early losses. The same is true for the television industry.