Early Media Research Methods

During most of the nineteenth century, philosophers such as Alexis de Tocqueville based their analysis of news and print media on moral and political arguments.3 More scientific approaches to mass media research did not emerge until the late 1920s and 1930s. In 1920, Walter Lippmann’s Liberty and the News called on journalists to operate more like scientific researchers in gathering and analyzing facts. Lippmann’s next book, Public Opinion (1922), was the first to apply the principles of psychology to journalism. Considered by many academics to be “the founding book in American media studies,”4 Public Opinion deepened Americans’ understanding of the effect of media, emphasizing data collection and numerical measurement. According to media historian Daniel Czitrom, by the 1930s “an aggressively empirical spirit, stressing new and increasingly sophisticated research techniques, characterized the study of modern communication in America.”5 Czitrom traces four trends between 1930 and 1960 that contributed to the rise of modern media research: propaganda analysis, public opinion research, social psychology studies, and marketing research.

Propaganda Analysis

Propaganda analysis was a major early focus of mass media research. After World War I, some researchers began studying how governments used propaganda to advance the war effort. They found that during the war, governments routinely relied on propaganda divisions to spread “information” to the public. Though propaganda was considered important for mobilizing public support during the war, these postwar researchers criticized it as “partisan appeal based on half-truths and devious manipulation of communication channels.”6 Harold Lasswell’s 1927 study Propaganda Technique in the World War defined propaganda as “the control of opinion by significant symbols, … by stories, rumors, reports, pictures and other forms of social communication.”7

Public Opinion Research

After the second world war, researchers went beyond the study of wartime propaganda and began examining how the mass media filter information and shape public attitudes. Social scientists explored these questions by conducting public opinion research through citizen surveys and polls.

Public opinion research on diverse populations has provided insights into how different groups view major national events, such as elections, and how those views affect their behavior. Journalists, however, became increasingly dependent on polls, particularly for political insight.

Today, some critics argue that this heavy reliance on measured public opinion adversely affects Americans’ participation in the political process. For example, people who read poll projections and get the sense that few others are voting for their favored candidate may not bother casting a ballot. “Why should I vote,” they tell themselves, “if my vote isn’t going to make a difference?” Some critics of incessant polling argue that polls mainly measure opinions on topics of interest to business, government, academics, and the mainstream news media. The public responds passively to polls, without getting anything of value in return. Professional pollsters object to pseudo-polls—typically call-in, online, or person-in-the-street polls that the news media use to address a “question of the day.” Such polls, which do not use a random sample of the population and are therefore not representative of the population as a whole, nevertheless persist on news and entertainment Web sites, radio, and television news programs.

Social Psychology Studies

Whereas opinion polls measure public attitudes, social psychology studies measure the behavior, attitudes, and cognition of individuals. The Payne Fund Studies—the most influential early social psychology media studies—comprised thirteen research projects conducted by social psychologists between 1929 and 1932. Named after the private philanthropic organization that funded the research, the Payne Fund Studies were a response to a growing national concern about the effects of motion pictures on young people. The studies, which some politicians later used to attack the movie industry, linked frequent movie attendance to juvenile delinquency, promiscuity, and other problematic behaviors, arguing that movies took “emotional possession” of young filmgoers.8

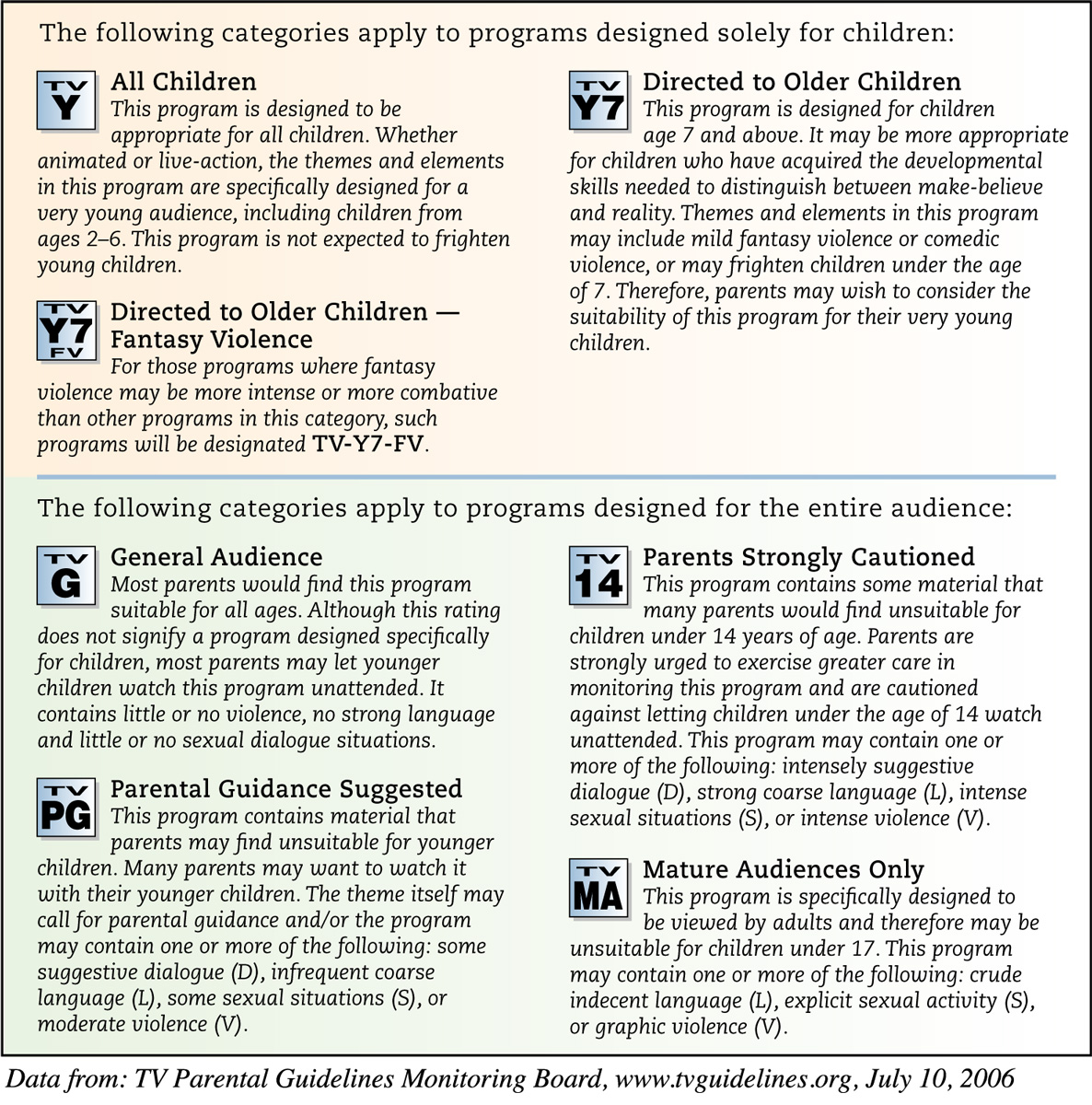

The conclusions of this and other Payne Fund Studies contributed to the establishment of the Motion Picture Production Code, which tamed movie content from the 1930s through the 1950s (see Chapter 13). As forerunners of today’s research into TV violence and aggression, the Payne Fund Studies became the model for media research, although social psychology is also used to study the mass media’s relationship to body image, gender norms, political participation, and a wide range of other topics. (See Figure 15.1 for one example of a contemporary policy that has developed from media research. See also “Media Literacy Case Study: The Effects of Television in a Post-TV World” on pages 504–505.)

Marketing Research

Marketing research emerged in the 1920s, when advertisers and consumer product companies began conducting surveys on consumer buying habits and other behaviors. For example, rating systems arose that measured how many people were listening to commercial radio on a given night. By the 1930s, radio networks, advertisers, large stations, and advertising agencies all subscribed to ratings services. However, compared with print media, whose circulation departments kept track of customers’ names and addresses, radio listeners were more difficult to trace. The problem prompted experts to develop increasingly sophisticated market-research methods to determine consumer preferences and media use, such as direct-mail diaries, television meters, phone surveys, telemarketing, and eventually Internet tracking. In many instances, product companies paid consumers a small fee to take part in these studies.