Social Scientific Research

Concerns about public opinion measurements, propaganda, and the impact of media on society intensified just as journalism and mass communication departments gained popularity in colleges and universities. As these forces dovetailed, media researchers looked increasingly to behavioral science as the basis of their work. Between 1930 and 1960, “who says what to whom with what effect” became the key question “defining the scope and problems of American communications research.”9 To address this question, researchers asked more specific questions, such as, If children watch a lot of TV cartoons (stimulus or cause), will this influence their behavior toward their peers (response or effect)? New social scientific models arose to measure and explain such connections—which researchers referred to as media effects.

Early Models of Media Effects

Between the 1930s and the 1970s, media researchers developed several paradigms about how media affect individuals’ behavior. These models were known as hypodermic needle, minimal effects, and uses and gratifications.

Hypodermic Needle

The notion that powerful media adversely affect weak audiences has been labeled the hypodermic-needle (or magic bullet) model. It suggests that the media “shoot” their effects directly into unsuspecting victims.

One of the earliest challenges to this model came from a study of Orson Welles’s legendary October 30, 1938, radio broadcast of War of the Worlds. The broadcast presented H. G. Wells’s Martian-invasion novel in the form of a news report, which frightened millions of listeners who didn’t realize it was fictional (see Chapter 6). In 1940, radio researcher Hadley Cantril wrote a book-length study of the broadcast and its aftermath, titled The Invasion from Mars: A Study in the Psychology of Panic. Cantril argued that contrary to what the hypodermic-needle model suggested, not all listeners thought the radio program was a real news report. In fact, the relatively few listeners who thought there was an actual invasion from Mars were those who not only tuned in late and missed the disclaimer at the beginning of the broadcast but also were predisposed (because of religious beliefs) to think that the end of the world was actually near. Although social scientists have since disproved the hypodermic-needle model, many people still subscribe to it, particularly when considering the media’s impact on children.

Minimal Effects

Cantril’s research helped lay the groundwork for the minimal-effects (or limited effects) model proposed by some media researchers. With the rise of empirical research techniques, social scientists began discovering and demonstrating that media alone do not cause people to change their attitudes and behaviors. After conducting controlled experiments and surveys, researchers argued that people generally engage in selective exposure and selective retention with regard to media. That is, people expose themselves to media messages most familiar to them, and retain messages that confirm values and attitudes they already hold. Minimal-effects researchers have argued that in most cases, mass media reinforce existing behaviors and attitudes rather than change them.

Indeed, Joseph Klapper, in his 1960 research study The Effects of Mass Communication, found that mass media influenced only those individuals who did not already hold strong views on an issue. Media, Klapper added, had a greater impact on poor and uneducated audiences. Solidifying the minimal-effects argument, Klapper concluded that strong media effects occur largely at an individual level and do not appear to have large-scale, measurable, and direct effects on society as a whole.10

Uses and Gratifications

The uses and gratifications model arose to challenge the notion that people are passive recipients of media. This model holds that people instead actively engage in using media to satisfy various emotional or intellectual needs—for example, turning on the TV in the house not only to be entertained but also to create an “electronic hearth,” making the space feel more warm and alive. Researchers supporting this model use in-depth interviews to supplement survey questionnaires. Through these interviews, they study the ways in which people use media. Instead of asking, “What effects do media have on us?” these researchers ask, “Why do we use media?”

Although the uses and gratifications model addresses the functions of the mass media for individuals, it does not address important questions related to the impact of the media on society. Consequently, the uses and gratifications model has never become a dominant or enduring paradigm in media research. But the rise of Internet-related media technologies has brought a resurgence of uses and gratifications research to understand why people use new media.

Conducting Social Scientific Media Research

As researchers investigated various theories about how media affect people, they also developed different approaches to conducting their research. These approaches vary depending on whether the research originates in the private or the public sector. Private research, sometimes called proprietary research, is generally conducted for a business, a corporation, or even a political campaign. It typically addresses some real-life problem or need. Public research usually takes place in academic and government settings. It tries to clarify, explain, or predict—in other words, to theorize about—the effects of mass media rather than to address a consumer problem.

Most media research today focuses on media’s impact on human characteristics such as learning, attitudes, aggression, and voting habits. This research employs the scientific method, which consists of seven steps:

Identify the problem to be researched.

Review existing research and theories related to the problem.

Develop working hypotheses or predictions about what the study might find.

Determine an appropriate method or research design.

Collect information or relevant data.

Analyze results to see whether they verify the hypotheses.

Interpret the implications of the study.

The scientific method relies on objectivity (eliminating bias and judgments on the part of researchers), reliability (getting the same answers or outcomes from a study or measure during repeated testing), and validity (demonstrating that a study actually measures what it claims to measure).

A key step in using the scientific method is posing one or more hypotheses: tentative general statements that predict either the influence of an independent variable on a dependent variable, or relationships between variables. For example, a researcher might hypothesize that frequent TV viewing among adolescents (independent variable) causes poor academic performance (dependent variable). Or a researcher might hypothesize that playing first-person-shooter video games (independent variable) is associated with aggression in children (dependent variable).

Researchers using the scientific method may employ experiments or survey research in their investigations.

Experiments

Like all studies that use the scientific method, experiments in media research isolate some aspect of content; suggest a hypothesis; and manipulate variables to discover a particular medium’s impact on people’s attitudes, emotions, or behavior. To test whether a hypothesis is true, researchers expose an experimental group—the group under study—to selected media images or messages. To en-sure valid results, researchers also use a control group, which is not exposed to the selected media content and thus serves as a basis for comparison. Subjects are picked for each group through random assignment, meaning that each subject has an equal chance of being placed in either group.

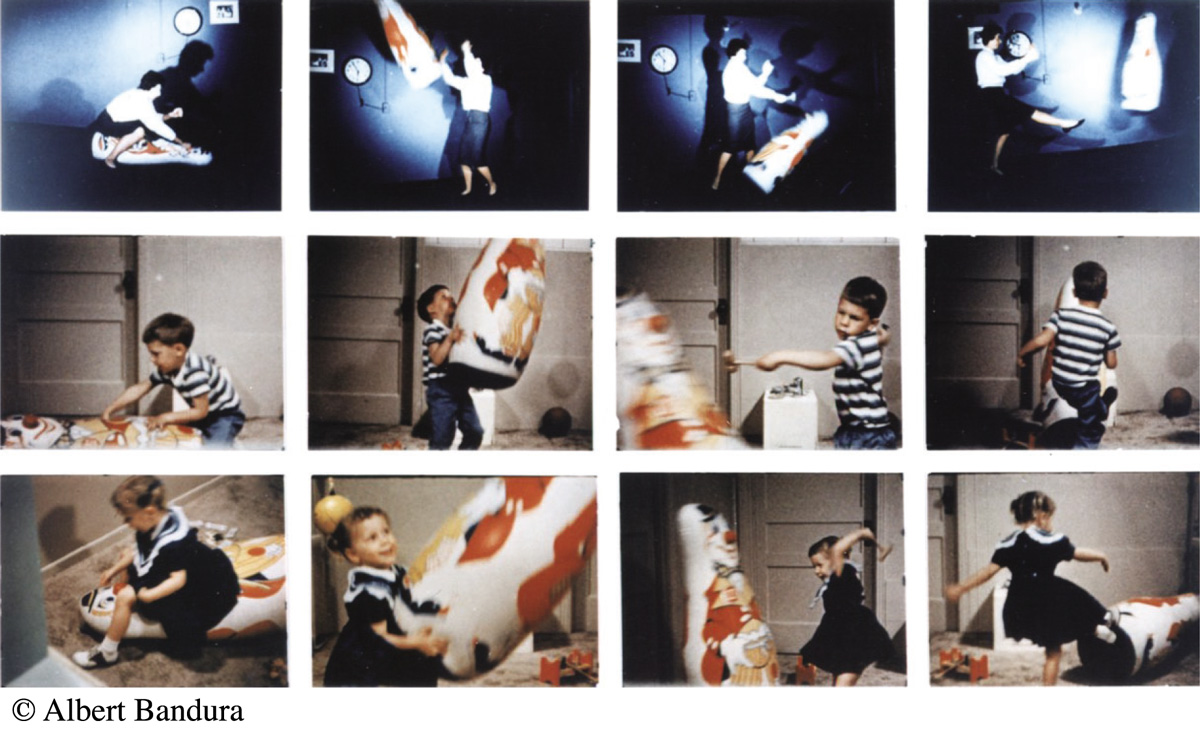

For instance, suppose researchers wanted to test the effects of violent films on preadolescent boys. The study might take a group of ten-year-olds and randomly assign them to two groups. The experimental group then watches a violent action movie that the control group does not see. Later, both groups are exposed to a staged fight between two other boys, and researchers watch how each group responds. If the control subjects try to break up the fight but the experimental subjects do not, researchers might conclude that the violent film caused the difference in the groups’ responses (see the “Bobo doll” experiment photos).

When experiments carefully account for independent variables through random assignment, they generally work well to substantiate cause-effect hypotheses. Although experiments are sometimes conducted in field settings, where people can be observed using media in their everyday environments, researchers have less control over variables in these settings. Conversely, a weakness of more carefully controlled experiments is that they are often conducted in the unnatural conditions of a laboratory environment, which can affect the behavior of the experimental subjects.

Survey Research

Through survey research, investigators collect and measure data taken from a group of respondents regarding their attitudes, knowledge, or behavior. Using random sampling techniques that give each potential subject an equal chance to be included in the survey, this research method draws on much larger populations than those used in experimental studies. Researchers can conduct surveys through direct mail, personal interviews, telephone calls, e-mail, and Web sites, thus accumulating large quantities of information from diverse cross sections of people. These data enable researchers to examine demographic factors in addition to responses to questions related to the survey topic.

Surveys offer other benefits as well. Because the randomized sample size is large, researchers can usually generalize their findings to the larger society as well as investigate populations over a long period of time. In addition, they can use the extensive government and academic survey databases now widely available to conduct longitudinal studies, in which they compare new studies with those conducted years earlier.

But like experiments, surveys also have several drawbacks. First, they cannot show cause-effect relationships. They can only show correlations—or associations—between two variables. For example, a random survey of ten-year-old boys that asks about their behavior might demonstrate that a correlation exists between acting aggressively and watching violent TV programs. But this correlation does not identify the cause and the effect. (Perhaps people who are already aggressive choose to watch violent TV programs.) Second, surveys are only as good as the wording of their questions and the answer choices they present. Thus, a poorly designed survey can produce misleading results.

Content Analysis

As social scientific media researchers developed theories about the mass media, it became increasingly important to more precisely describe the media content being studied. As a corrective, they developed a method known as content analysis to systematically describe various types of media content.

Content analysis involves defining terms and developing a coding scheme so that whatever is being studied—acts of violence in movies, representations of women in television commercials, the treatment of political candidates in news reports—can be accurately judged and counted. One annual content analysis study is conducted by GLAAD each year to count the quantity, quality, and diversity of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) characters on television. In 2014, GLAAD’s content analysis found that MTV led all networks, with 49 percent of its primetime programming hours featuring LGBT characters (followed by FX, ABC Family, and NBC). On the other end of the GLAAD list, only 9 percent of TNT’s prime-time programming included LGBT characters; A&E had 6 percent, and the History Channel came in last with no LGBT representations at all in its prime-time programming. The report also noted that some of the most “groundbreaking and fully realized depictions” of transgender characters was happening on new online content creators like Netflix and Amazon, with shows like Orange Is the New Black and Transparent.11 Content analysis has its own limitations. For one thing, this technique does not measure the effects of various media messages on audiences or explain how those messages are presented. Moreover, problems of definition arise. For instance, how do researchers distinguish slapstick cartoon aggression from the violent murders or rapes shown during an evening police drama?

Contemporary Media Effects Theories

By the 1960s, several departments of mass communication began graduating Ph.D.-level researchers (the first had been at the University of Iowa in 1948) schooled in experiment and survey research techniques as well as content analysis. These researchers began developing new theories about how media affect people. Five particularly influential contemporary theories emerged. These are known as social learning theory, agenda-setting theory, the cultivation effect theory, the spiral of silence theory, and the third-person effect theory.

Social Learning Theory

Some of the best-known studies suggesting a link between mass media and behavior are the “Bobo doll” experiments, conducted on children by psychologist Albert Bandura and his colleagues at Stanford University in the 1960s. Although many researchers criticized the use of Bobo dolls as an experimental device (since the point of playing with Bobo dolls is to hit them), Bandura argued that the experiments demonstrated a link between violent media programs, such as those on television, and aggressive behavior. Bandura developed social learning theory, which he believed involved a four-step process: attention (the subject must attend to the media and witness the aggressive behavior), retention (the subject must retain the memory of what he or she saw for later retrieval), motor reproduction (the subject must be able to physically imitate the behavior), and motivation (there must be a social reward or reinforcement to encourage modeling of the behavior).

Supporters of social learning theory often cite real-life imitations of aggression depicted in media (such as the Columbine massacre) as evidence that the theory is correct. Critics argue that real-life violence actually stems from larger social problems (such as poverty or mental illness), and that the theory makes mass media the scapegoats for those larger problems.

Agenda-Setting Theory

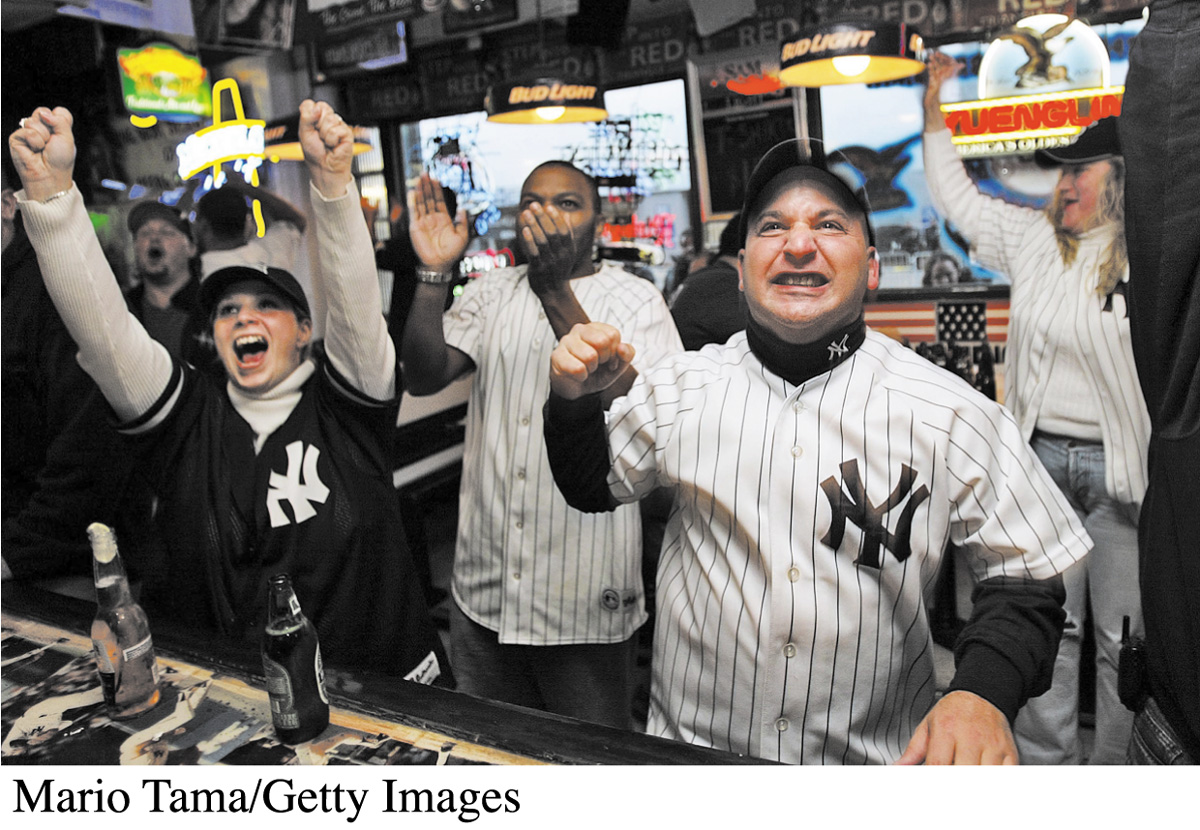

Researchers who hold the agenda-setting theory believe that when mass media focus their attention on particular events or issues, they determine—that is, set the agenda for—what people discuss and what they pay attention to. Media thus do not so much tell us what to think as what to think about.

The first investigations into the possibility of agenda-setting began in the late 1960s, when scholars Maxwell McCombs and Donald Shaw compared issues cited by undecided voters on election day with issues covered heavily by the media. Since then, researchers exploring this theory have demonstrated that the more stories the news media do on a particular subject, the more importance audiences attach to that subject. For instance, the extensive news coverage of Hurricane Katrina in fall 2005 sparked a corresponding increase in public concern about the disaster. Today, with national news coverage of the aftereffects of Katrina almost nonexistent, public interest in the impact of Katrina has ebbed—even though many of the areas affected by the hurricane still lie in ruins.

The Cultivation Effect Theory

The cultivation effect theory holds that heavy viewing of TV leads individuals to perceive the world in ways consistent with television portrayals. The major research into this hypothesis grew from the TV violence profiles of George Gerbner and his colleagues, who attempted to make broad generalizations about the impact of televised violence. Beginning in the late 1960s, these social scientists categorized and counted different types of violent acts shown on network television. Using a methodology that combines annual content analyses of TV violence with surveys, the cultivation effect suggests that the more time individuals spend viewing television and absorbing its viewpoints, the more likely their views of social reality will be “cultivated” by the images and portrayals they see on television.12 For example, Gerbner’s studies concluded that although fewer than 1 percent of Americans are victims of violent crime in any single year, people who watch a lot of television tend to overestimate that percentage.

Some critics have charged that cultivation research has provided limited evidence to support its findings. In addition, some have argued that the cultivation effects recorded by Gerbner’s studies have been minimal. When compared side by side, these critics argue, perceptions of heavy television viewers and nonviewers regarding how dangerous the world is are virtually identical.

The Spiral of Silence Theory

Developed by German communication theorist Elisabeth Noelle-Neumann in the 1970s and 1980s, the spiral of silence theory links mass media, social psychology, and public opinion formation. The theory proposes that those who believe that their views on controversial issues are in the minority will keep their views to themselves for fear of social isolation. The theory is based on social psychology studies, such as the classic conformity studies of Solomon Asch in 1951. In Asch’s study on the effects of group pressure, he demonstrated that a test subject is more likely to give clearly wrong answers to questions about line lengths if everyone else in the room (all secret confederates of the experimenter) unanimously state an incorrect answer. Noelle-Neumann argued that this effect is exacerbated by mass media, particularly television, which can quickly and widely communicate a real or presumed majority public opinion.

Noelle-Neumann acknowledges that not everyone keeps quiet if they think they hold a minority view. In many cases, “hard-core nonconformists” exist and remain vocal even in the face of possible social isolation. These individuals can even change public opinion by continuing to voice their views.

The Third-Person Effect Theory

Identified in a 1983 study by W. Phillips Davison, the third-person effect theory suggests that people believe others are more affected by media messages than they are themselves. In other words, this theory posits the idea that “we” can escape the worst effects of media while still worrying about people who are younger, less educated, less informed, or otherwise less capable of guarding against media influence.

Under this theory, we might fear that other people will, for example, take tabloids seriously, imitate violent movies, or get addicted to the Internet, while dismissing the idea that any of those things could happen to us. It has been argued that the third-person effect is instrumental in censorship, as it would allow censors to assume immunity to the negative effects of any supposedly dangerous media they must examine.

Evaluating Social Scientific Research

Media effects research has deepened our understanding of the mass media. This wealth of research exists partly because funding for studies on media’s impact on young people remains popular among politicians and has drawn ready government support since the 1960s. But funding restricts the scope of some media effects research, particularly if the agendas of government agencies, businesses, or other entities do not align with researchers’ interests. Moreover, because media effects research operates best in examining media’s impact on individual behavior, few of these studies explore how media shape larger community and social life. Some research has begun to address these deficits, as well as to explore the impact of media technology on international communication.