The Evolution of Mass Communication

The mass media surrounding us have their roots in mass communication. Mass media are the industries that create and distribute songs, novels, newspapers, movies, Internet services, TV shows, magazines, and other products to large numbers of people. The word media is a Latin plural form of the singular noun medium, meaning an intervening material or substance through which something else is conveyed or distributed.

macmillanhighered.com/mediaessentials3e

Use LearningCurve to review concepts from this chapter.

We can trace the historical development of media through several eras, all of which still operate to varying degrees. These eras are oral, written, print, electronic, and digital. In the first two eras (oral and written), media existed only in tribal or feudal communities and agricultural economies. In the last three eras (print, electronic, and digital), media became vehicles for mass communication: the creation and use of symbols (e.g., languages, Morse code, motion pictures, and binary computer codes) that convey information and meaning to large and diverse audiences through all manner of channels.

Although the telegraph meant that by the middle of the 1800s reporters could almost instantly send a report to their newspaper across the country, getting that news out to a mass audience still had to wait on printing and delivery of a physical object. But with the start of the electronic age in the early twentieth century, radio and then television made mass communication even more widely, and instantly, accessible. If a person were in range of a transmitter, news and entertainment now came at the flick of a switch. By the end of the twentieth century, the Internet revolutionized the entire field of mass communication, and continues to change it today. Consider, for example, that a smartphone that fits into the palm of a person’s hand offers every earlier form of communication anywhere there is a Wi-Fi or cellular signal. One could use the phone to make a call or video chat (oral communication), send a text or an e-mail (written communication), read a book (print communication), listen to an online radio station or watch a television program on a service like Hulu (electronic communication), and then send a tweet about the movie they watched on Netflix (digital communication). As shown throughout this book, older forms of communication don’t go away but are adapted and converged with newer forms and technologies.

7

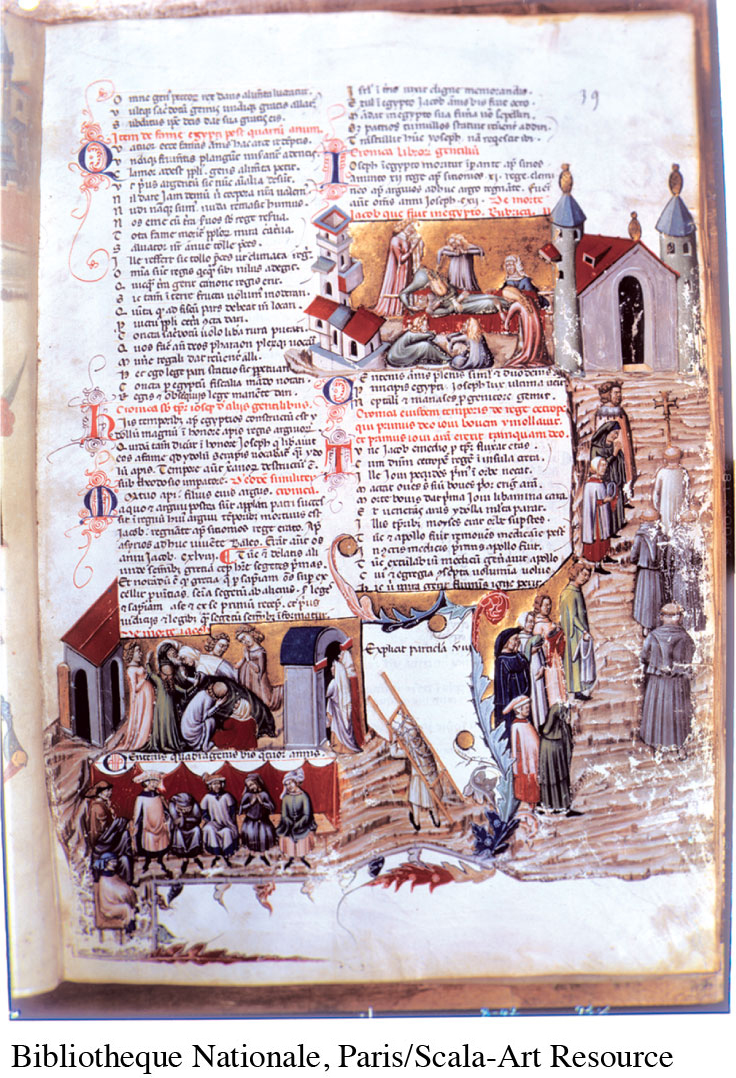

The Oral and Written Eras

In most early societies, information and knowledge first circulated slowly through oral (spoken) traditions passed on by poets, teachers, and tribal storytellers. However, as alphabets and the written word emerged, a manuscript (written) culture developed and eventually overshadowed oral communication. Painstakingly documented and transcribed by philosophers, monks, and stenographers, manuscripts were commissioned by members of the ruling classes, who used them to record religious works and prayers, literature, and personal chronicles. Working people, most of whom were illiterate, rarely saw manuscripts. The shift from oral to written communication created a wide gap between rulers and the ruled in terms of the two groups’ education levels and economic welfare.

These trends in oral and written communication unfolded slowly over many centuries. Although exact time frames are disputed, historians generally date the oral and written eras as ranging from 1000 BCE to the mid-fifteenth century. Moreover, the transition from oral to written communication wasn’t necessarily smooth. For example, some philosophers saw oral traditions (including exploration of questions and answers through dialogue between teachers and students) as superior. They feared that the written word would hamper conversation between people.

The Print Era

What we recognize as modern printing—the wide dissemination of many copies of particular manuscripts—became practical in Europe around the middle of the fifteenth century. At this time, Johannes Gutenberg’s invention of movable metallic type and the printing press in Germany ushered in the modern print era. Printing presses—and the publications they enabled—spread rapidly across Europe in the late 1400s and early 1500s. But early on, many books were large, elaborate, and expensive. It took months to illustrate and publish these volumes, which were typically purchased by wealthy aristocrats, royal families, church leaders, prominent merchants, and powerful politicians.

8

In the following centuries, printers reduced the size and cost of books, making them available and affordable to more people. Books were then being mass-produced, making them the first mass-marketed products in history. This development spurred four significant changes: an increasing resistance to authority, the rise of new socioeconomic classes, the spread of literacy, and a focus on individualism.

Resistance to Authority

Since mass-produced printed materials could spread information and ideas faster and farther than ever before, writers could use print to disseminate views that challenged traditional civic doctrine and religious authority. This paved the way for major social and cultural changes, such as the Protestant Reformation and the rise of modern nationalism. People who read contradictory views began resisting traditional clerical authority. With easier access to information about events in nearby places, people also started seeing themselves not merely as members of families, isolated communities, or tribes, but as participants in larger social units—nation-states—whose interests were broader than local or regional concerns.

New Socioeconomic Classes

Eventually, mass production of books inspired mass production of other goods. This development led to the Industrial Revolution and modern capitalism in the mid-nineteenth century. The nineteenth and twentieth centuries saw the rise of a consumer culture, which encouraged mass consumption to match the output of mass production. The revolution in industry also sparked the emergence of a middle class. This class was composed of people who were neither poor laborers nor wealthy political or religious leaders, but who made modest livings as merchants, artisans, and service professionals, such as lawyers and doctors.

In addition to a middle class, the Industrial Revolution also gave rise to an elite class of business owners and managers who acquired the kind of influence once held only by the nobility or the clergy. These groups soon discovered that they could use print media to distribute information and maintain social order.

Spreading Literacy

9

Although print media secured authority figures’ power, the mass publication of pamphlets, magazines, and books also began democratizing knowledge—making it available to more and more people. Literacy rates rose among the working and middle classes, and some rulers fought back. In England, for instance, the monarchy controlled printing press licenses until the early nineteenth century to constrain literacy and therefore sustain the Crown’s power over the populace. Even today, governments in many countries worldwide control presses, access to paper, and advertising and distribution channels for the same reason. In most industrialized countries, such efforts at control have met with only limited success. After all, building an industrialized economy requires a more educated workforce, and printed literature and textbooks support that education.

Focus on Individualism

The print revolution also nourished the idea of individualism. People came to rely less on their local community and their commercial, religious, and political leaders for guidance on how to live their lives. Instead, they read various ideas and arguments, and came up with their own answers to life’s great questions. By the mid-nineteenth century, individualism had spread into the realm of commerce. There, it took the form of increased resistance to government interference in the affairs of self-reliant entrepreneurs. Over the next century, individualism became a fundamental value in American society.

The Electronic and Digital Eras

In Europe and America, the rise of industry completely transformed everyday life, with factories replacing farms as the main centers of work and production. During the 1880s, roughly 80 percent of Americans lived on farms and in small towns; by the 1920s and 1930s, most had moved to urban areas, where new industries and economic opportunities beckoned. This shift set the stage for the final two eras in mass communication: the electronic era (whose key innovations included the telegraph, radio, and television) and the digital era (whose flagship invention is the Internet).

The Electronic Era

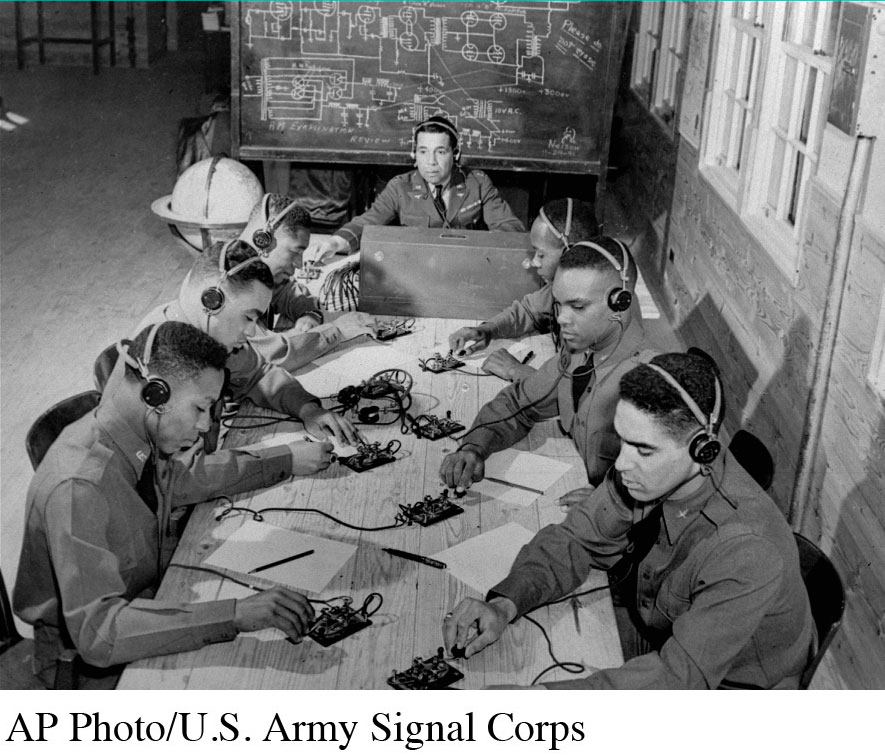

In America, the gradual transformation from an industrial, print-based society to one fueled by electronic innovation began with the development of the telegraph in the 1840s. Featuring dot-dash electronic signals, the telegraph made media messages instantaneous, no longer reliant on stagecoaches, ships, or the pony express. It also enabled military, business, and political leaders to coordinate commercial and military operations more easily than ever. And it laid the groundwork for future technological developments, such as wireless telegraphy, the fax machine, and the cell phone (all of which ultimately led to the telegraph’s demise).

10

The development of film at the start of the twentieth century and radio in the 1920s were important milestones, but the electronic era really took off in the 1950s and 1960s with the arrival of television—a medium that powerfully reshaped American life.

The Digital Era

With the arrival of cutting-edge communication gadgetry—ever-smaller personal computers, cable TV, e-mail, DVDs, DVRs, direct broadcast satellites, cell phones, PDAs—the electronic era gave way to the digital era. In digital communication, images, texts, and sounds are converted (encoded) into electronic signals (represented as combinations of ones and zeros) that are then reassembled (decoded) as a precise reproduction of, say, a TV picture, a magazine article, a song, or a voice on the telephone. On the Internet, various images, text, and sounds are digitally reproduced and transmitted globally.

New technologies, particularly cable television and the Internet, have developed so quickly that those who had long controlled the dispersal of information—for example, newspaper editors and network television news producers—have lost some of that power. Moreover, e-mail and text messages—digital versions of both oral and written culture—now perform some of the functions of the postal service and are outpacing some governments’ attempts to control communications beyond national borders.

Media Convergence

The electronic and digital eras have ushered in the phenomenon of media convergence, a term that has two very different meanings. According to one meaning, media convergence is the technological merging of content in different mass media. For example, magazine articles and radio programs are also accessible on the Internet; and songs, TV shows, and movies are now available on computers, iPods, and cell phones.

Such technological convergence is not entirely new. For instance, in the late 1920s, the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) purchased the Victor Talking Machine Company and introduced machines that could play both radio and recorded music. However, contemporary media convergence is much broader because it involves digital content across a wider array of media.

11

The term media convergence can also be used to describe a particular business model by which a company consolidates various media holdings—such as cable connections, phone services, television transmissions, and Internet access—under one corporate umbrella. The goal of such consolidation is not necessarily to offer consumers more choices in their media but to better manage resources, lower costs, and maximize profits. For example, a company that owns TV stations, radio outlets, and newspapers in multiple markets—as well as in the same cities—can deploy one reporter or producer to create three or four versions of the same story for various media outlets. Thus, the company can employ fewer people than if it owned only one media outlet.