A Closer Look at the Cultural Model: Surveying the Cultural Landscape

In the pages that follow, we examine the cultural model of media literacy, which provides many ways to study media content through the lens of culture. We discuss two metaphors researchers use to describe the way people judge media content, and present ways to trace changes in our cultural values as media adapt and change.

The “Culture as Skyscraper” Metaphor

Throughout the twentieth century, many Americans envisioned our nation’s culture as consisting of ascending levels of superiority—like floors in a skyscraper. They identified high culture (the top floors of the building) with good taste, higher education, and fine art supported by wealthy patrons and corporate donors. And they associated low or popular culture (the bottom floors) with the questionable tastes of the masses, who lapped up the commercial junk circulated by the mass media, such as reality TV shows, celebrity gossip Web sites, and action films.

Some cultural researchers have pointed out that this high–low hierarchy has become so entrenched that it powerfully influences how we view and discuss culture today.3 For example, people who subscribe to the hierarchy metaphor believe that low culture prevents people (students in particular) from appreciating fine art, exploits high culture by transforming classic works into simplistic forms, and promotes a throwaway ethic. These same critics accuse low culture of driving out higher forms of culture. They also argue that it inhibits political discourse and social change by making people so addicted to mass-produced media that they lose their ability to see and challenge social inequities (also referred to as the Big Mac Theory).4

The “Culture as Map” Metaphor

Other researchers think of culture as a map. In this metaphor, culture—rather than being a vertically organized structure—is an ongoing process that accommodates diverse tastes. Cultural phenomena, including media—printed materials we read, movies and TV programs we watch, songs and radio shows we listen to—can take us to places that are conventional, recognizable, stable, and comforting. However, they can also take us to places that are innovative, unfamiliar, unstable, and challenging.

Human beings are attracted to both consistency and change, and cultural media researchers have pointed out that most media can satisfy both of those desires. For example, a movie can contain elements that are familiar to us (such as particular plots) as well as elements that are completely new and strange (such as a cinematic technique we’ve never seen before).

Tracing Changes in Values

In addition to examining metaphors of culture that we use to understand media’s role in our lives, cultural researchers examine the ways in which our values have changed along with changes in mass media. Researchers have been particularly interested in how values have shifted during the modern era and the postmodern period.

The Modern Era

From the Industrial Revolution to the mid-twentieth century—which historians call the modern era—four values came into sharp focus across the American cultural landscape. These values were influenced by developments that unfolded during the era and the media’s responses to those developments:

Working efficiently. As businesses used new technology to create efficient manufacturing centers and produce inexpensive products more cheaply and profitably, advertisers (who operate in all mass media) spread the word about new gadgets that could save Americans time and labor, reinforcing the benefits of efficiency.

Celebrating the individual. Media described and interpreted new scientific discoveries, enabling ordinary citizens to gain access to new ideas beyond what their religious leaders and local politicians communicated to them. With access to novel ideas, people began celebrating the individual’s power to pick and choose from ideas instead of merely following what leaders told them.

Believing in a rational order. Being modern also meant valuing logic and reason and viewing the world as a rational place. In this orderly place, the printed mass media—particularly newspapers—served to educate the citizenry, helping to build and maintain an organized society.5

Rejecting tradition and embracing progress. Within the modern era was a shorter phenomenon: the Progressive Era. This period of political and social reform lasted roughly from the 1890s to the 1920s and inspired many Americans—and mass media—to break with tradition and embrace change. For example, journalists began focusing their reporting on immediate events. They ignored the foundational developments that led up to those events, further reinforcing the notion that the past matters far less than the present and the future.

The Postmodern Period

In the postmodern period—from roughly the mid-twentieth century to today—cultural values changed shape once more, influenced again by developments in our society and the media’s responses to those developments. Cultural researchers have identified the following dominant values in today’s postmodern period:

Celebrating populism. As a political idea, populism tries to appeal to ordinary people by setting up a conflict between “the people” and “the elite.” For example, populist politicians often run ads criticizing big corporations and political favoritism. And many famous film actors champion oppressed groups, even though their work makes them wealthy global icons of consumerist culture.

Page 22Reviving older cultural styles. Mass media now borrow and then transform cultural styles from the modern era. For example, in music, hip-hop deejays and performers sample old R&B, soul, and rock classics to reinvent songs. And in the noir genre of moviemaking, directors use moody photography and retro costuming to create the same look and feel of movies crafted in the earlier era.

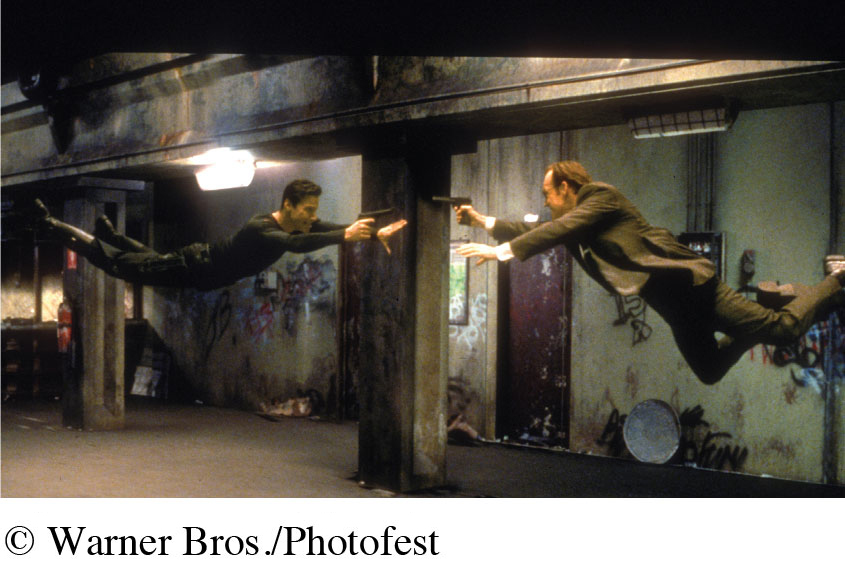

Embracing technology. Even as we and our media can’t seem to get enough of retro cultural styles, we passionately embrace new technologies. The huge popularity of movies that feature technology at their core—like Guardians of the Galaxy and Interstellar—testifies to this paradox.

Interest in the supernatural. Some people have begun challenging the argument that scientific reasoning is the only way to interpret the world, and have gravitated toward traditional religion or the supernatural. Mass media reflect this shift. For example, since the late 1980s, a host of popular TV programs emerged that featured mystical themes—including Twin Peaks, The X-Files, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Supernatural, American Horror Story, and The Vampire Diaries.